|

by Yves Smith

October 24, 2019

from

NakedCapitalism Website

With 2019 shaping up to

be another 1848, it's hard to provide in-depth commentary on so many

protests. Nevertheless, Lambert hopes to provide a high-level piece

soon.

In the meantime, this post on Chile will hopefully fill in some of

the gaps as well as encourage readers who have insight to provide

additional comments and highlight any points that seem inaccurate or

incomplete.

It's also worth noting that Pinochet's Chicago School experiment ran

quickly into the ditch.

From ECONNED:

Chile has been

widely, and falsely, cited as a successful "free markets"

experiment.

Even though Chilean

dictator Augusto Pinochet's aggressive implementation of

reforms that were devised by followers of the

Chicago School of Economics

led to speculation and looting followed by a bust, it was touted

in the United States as a triumph.

Milton Friedman claimed in

1982 that Pinochet,

"has supported a

fully free-market economy as a matter of principle. Chile is

an economic miracle."

The State Department

deemed Chile to be,

"a casebook study

in sound economic management."

Those assertions do

not stand up to the most cursory examination. Even the temporary

gains scored by Chile relied on heavy-handed government

intervention….

The "Chicago

boys," a group of thirty Chileans who had become

followers of Friedman as students at the University of Chicago,

assumed control of most economic policy roles. In 1975, the

finance minister announced the new program: opening of trade,

deregulation, privatization, and deep cuts in public spending.

The economy initially appeared to respond well to these changes

as foreign money flowed in and inflation fell. But this seeming

prosperity was largely a speculative bubble and an export boom.

The newly liberalized

economy went heavily into debt, with the funds going mainly to

real estate, business acquisitions, and consumer spending rather

than productive investment.

Some state assets

were sold at huge discounts to insiders. For instance,

industrial combines, or grupos, acquired banks at a 40%

discount to book value, and then used them to provide loans to

the grupos to buy up manufacturers.

In 1979, when the government set a currency peg too high, it set

the stage for what Nobel Prize winner George Akerlof and

Stanford's Paul Romer call "looting" (we discuss this

syndrome in chapter 7).

Entrepreneurs, rather

than taking risk in the normal fashion, by gambling on success,

instead engage in bankruptcy fraud.

They borrow against

their companies and find ways to siphon funds to themselves and

affiliates, either by overpaying themselves, extracting too much

in dividends, or moving funds to related parties.

The bubble worsened as banks gave low-interest-rate foreign

currency loans, knowing full when the peso fell. But it

permitted them to use the proceeds to seize more assets at

preferential prices, thanks to artificially cheap borrowing and

the eventual subsidy of default.

And the export boom, the other engine of growth, was, contrary

to stateside propaganda, not the result of "free market" reforms

either. The Pinochet regime did not reverse the Allende land

reforms and return farms to their former owners.

Instead, it practiced

what amounted to industrial policy and gave the farms to

middle-class entrepreneurs, who built fruit and wine businesses

that became successful exporters. The other major export was

copper, which remained in government hands.

And even in this growth period, the gains were concentrated

among the wealthy.

Unemployment rose to

16% and the distribution of income became more regressive.

The Catholic Church's soup

kitchens became a vital stopgap.

The bust came in late 1981.

Banks, on the

verge of collapse thanks to dodgy loans, cut lending.

GDP contracted

sharply in 1982 and 1983.

Manufacturing

output fell by 28% and unemployment rose to 20%.

The neoliberal regime

suddenly resorted to Keynesian backpedaling to quell violent

protests. The state seized a majority of the banks and

implemented tougher banking laws.

Pinochet restored the

minimum wage, the rights of unions to bargain, and launched a

program to create 500,000 jobs.

Chile in Flames...

by Democracia Abierta

October

22, 2019

from

OpenDemocracy Website

Spanish version

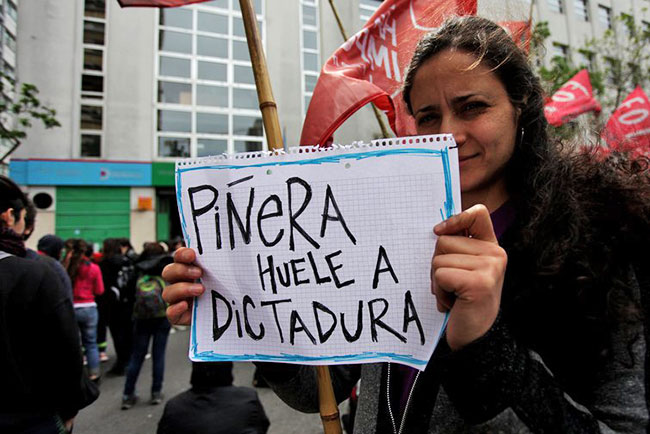

Protesters in Buenos Aires

demonstrate their support with Chilean citizens

by denouncing police violence outside the Consulate.

PA Images: All Rights Reserved.

In a country

where the minimum wage

of 70% of the

population

barely reaches

$700 USD per month,

the news from

Chilean president Piñera last week

that the fare

for a metro ticket in Santiago would rise

from 800 Chilean

Pesos to 830 ($1.15 USD)

hit hard...

Only a week after the

huge mobilizations in Ecuador that successfully toppled the

controversial 'paquetazo', the financial plan imposed on the South

American nation by the International Monetary Fund (IMF),

another Latin American country has risen up against the economic

policies of its government.

In a country where the minimum wage of 70% of the population barely

reaches $700 USD per month, the news from Chilean president Piñera

last week that the fare for a metro ticket in Santiago would rise

from 800 Chilean Pesos to 830 ($1.15 USD) hit hard.

Chile, a nation with a

long history of neoliberalism, has been unable to eradicate poverty

with privatization policies, and it is estimated that around 36% of

the urban population live in extreme poverty.

The supposed "economic miracle" of Chile, which received its name

from American economist Milton Friedman, was a set of

liberalizing economic measures put in place during the dictatorship

of Pinochet, that imposed a free market in the country with the

support from

the United States.

This economic system,

that continues to be implemented today in Chile, has benefitted

the economic elites whilst creating

inequality and suffering for

the majority...

It's hardly surprising

that thanks to these neoliberal reforms promoted by Friedman, the

90s became the lost decade of Latin America.

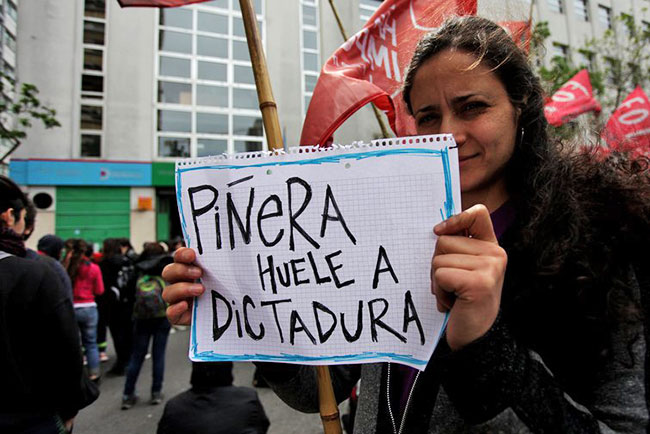

Tired of the economic policies of the government, students and

citizens took to the streets of Chile to protest against the rise in

price of the metro ticket, but in reality this was just the tip

of the iceberg...

They are in fact

protesting against many other social issues such as high tariffs for

electricity and gas, low pensions, and a completely unaffordable

health and education system.

Protesters burnt metro

stations and public busses, and they looted supermarkets and public

buildings.

When Piñera spoke to the nation on Saturday evening to

declare the suspension of the increase in metro fare, it was already

too late to contain the fury that had been unleashed.

Students and young people

kept marching and demanding justice, whilst the government declared

a State of Emergency and sent the army to the streets.

That's why we explain to you everything you need to know about the

current protests in Chile and why this explosion of violence is so

important in the region.

Police Violence

and Democracy in Chile

It's not the first time that police use violence against their own

citizens in Chile, a country which has a long history of repression

of the mapuche indigenous communities when they rise up

against the lack of government recognition of their territorial

rights.

This display of

state violence against citizens

comes only 30

years after the dictatorship of Pinochet

murdered and

disappeared over 40,000 Chileans

during its reign

of terror...

In fact, police violence against

mapuche communities resulted in the

murder of community leader of only 24 years of age, Camilo

Catrillanca, last year when he was passing through an area in

which a police operation was being carried out and suddenly found

himself in the middle of a shoot out.

A stray bullet hit him in

the head and murdered him instantly...

The protests that began in Santiago but that have now extended

themselves across the country, have so far caused around 11 deaths,

mostly due to violence at the hands of the police and the Chilean

army.

This display of state

violence against citizens comes only 30 years after the dictatorship

of Pinochet murdered and disappeared over 40,000 Chileans

during its reign of terror.

What's more, according to

the National Institute for Human Rights in Chile, there have

been 84 firearm casualties and over 1420 people detained since the

protests began last week.

The reaction from Piñera has focused on only the violent acts of the

protesters, contributing to the criminalization of the right to

protest in the country.

"We have invoked the

Law of State Security, not against citizens, but against a

handful of delinquents that have destroyed property and dreams

with violence and wickedness".

He justified police

repression of protests by declaring that "democracy has a right to

defend itself", however, he also expressed his intentions to reach

agreements to improve the standard of living for the lower and

middle classes of Chile.

The actions of the police

and the army over the past week has shocked one of the most

democratic countries in the world, and the second most

democratic of Latin America according to

Freedom House.

Chile's high score for freedom of assembly and protest may be

affected by the actions of the state against its citizens this week,

which seriously affect the right to protest by criminalizing all

individuals involved.

Neoliberal

Malaise Throughout the Region

Economic malaise in Chile is part of a regional trend that follows

recent protests in Ecuador, that also began as a product of

frustration regarding the economic policies of president Lenín

Moreno.

Chileans, no

doubt empowered

by the recent

protests in Ecuador,

have also taken

to the streets

with the same

hopes...

Protests in Ecuador began as a reaction against a set of economic

policies referred to as the 'paquetazo', which were a series of

austerity measures imposed on the country by the International

Monetary Fund (IMF)

in order to cut public spending and repay debts faster.

This included,

the elimination of

fuel subsidies, public salary cuts, and huge holiday reductions

for public employees...

Civil society, but mainly

indigenous groups led by the

Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of

Ecuador, took to the streets for weeks to protest against

the measures, until president Moreno declared that the 'paquetazo'

would no longer be implemented.

Chileans, no doubt empowered by the recent protests in Ecuador, have

also taken to the streets with the same hopes: that they will

achieve with their protests real change regarding how their

government manages the economy.

They also make it clear

that the poor management of the economy and imposition of neoliberal

policies have devastating and very human consequences for the most

disadvantaged of Latin America.

It's not only Chile and Ecuador that are facing massive citizen

unrest in the region.

Haití is also rising up

against the corrupt government of Jovenal Moïse and demanding

not only an explanation for what happened with millions of dollars

received from Venezuela, but also an end to neoliberal austerity

policies backed by their northern neighbor,

the US.

The

neoliberal model is in crisis, and

these protests have clearly demonstrated this.

Now, what happens in

Chile will depend on Piñera's 'capacity to negotiate' real

change, but if he fails at doing so, it will be impossible to

contain the rage that has already been unleashed in a country where

citizens are tired of injustice and inequality...

Source

|