|

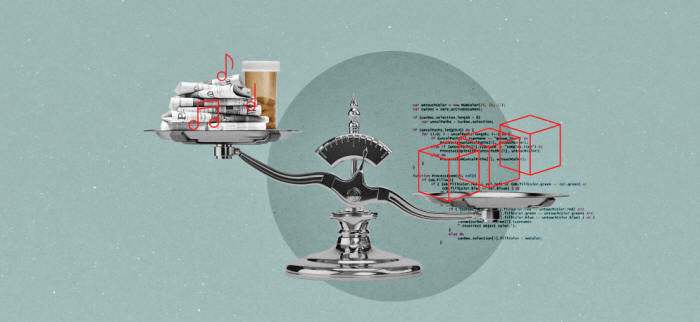

we must create a system where none is required.

In the physical world, it's easy to prove that trust is indeed warranted:

In the virtual world, 'trust' is far harder to envision.

From posting on social media, checking a bank balance, or uploading pictures to the cloud, we've been conditioned to assume that we won't get totally screwed every time we use the web. In recent years, however, thanks to various data breaches and general political mayhem, the era of suspension of disbelief in our digital lives is drawing to a close.

We've glimpsed the men behind the proverbial curtain at the big tech companies. Often, they are smaller than we imagined them. They definitely don't have our best interests at heart.

Heart has nothing to do

with their business models.

Raising awareness about the need for more data privacy and building a trustworthy web has been an obsession of mine:

At the end of that week, of the participants we surveyed, 70 percent said they wanted to fight for protection of our digital rights.

But here we are, more than a year later, and I've had to admit that for the vast majority of Americans (especially those on Capitol Hill), pushing the power button on a laptop still feels like summoning magic.

Few understand how it

works. Even fewer believe it can be improved. They wouldn't know

where to start. This moment of frustration is ripe for a

conversation

about blockchain.

But make no mistake, despite all the explainers and opinion pieces on Medium, most people have never heard the words "block" and "chain" morphed into one.

Just last month, I

visited a top high school in New Jersey and asked a group of 60

students if they'd heard of the blockchain. Not a single

18-year-old, many of whom are headed to Ivy League universities,

raised their hand.

But the actual link

between the two is far more interesting than I'd thought and worth

revisiting in the context of our growing distrust of Big Tech.

One mysterious coder, who went by the name Satoshi Nakamoto, thought he (or she, or they) had a technological way to bypass those unwieldy institutional systems.

Nakamoto posted a research paper on November 1, 2008, outlining an idea for a new digital currency.

The concept eliminated a middleman, like the government or a bank. No need to trust an institution to take care of your funds or a government to decide the value. No one person or entity would be in charge.

Instead, a network of

hundreds or thousands of computers would run special bitcoin

software, linking them together into a "distributed ledger"

called "the blockchain."

One of my favorite examples of blockchain's potential is in monitoring our food-supply chain.

Take the recent E. coli outbreak. Hundreds of people got sick in states across the country (in U.S.). Federal officials believe the contaminated lettuce came from farms in Yuma, Arizona, but the investigation is ongoing.

As one FDA update stated:

In a blockchain world, the process would move far faster. Every step in the delivery route would be tracked and linked, from farm to table.

In one test, Walmart compared conventional tracking methods with blockchain to see how quickly the source of some contaminated mangoes could be found.

The results? Seven days

versus 2.2 seconds...

Later, as trade routes became more complicated and global in scale, we created institutions like banks and regulators,

In the past two decades, marketplaces have moved online to platforms like Amazon and eBay.

Blockchain, according to Warburg, is the next evolution in how we'll do business.

It will bring us back to direct one-to-one trade by using decentralized technology. Eventually, humans will be taken out of the picture entirely, and the machines will be left to trade between themselves according to the rules we give them.

We won't need to trust or

even know the humans on the other end of any transaction.

Last month at the Ethereal conference, Joe Lubin, co-founder of a blockchain software called Ethereum and a leader in using blockchain for social good, told a group of reporters that personal privacy is one issue he thinks blockchain can fix.

With blockchain, Lubin claimed,

Imagine owning all your digital health care records and granting providers or insurance agents access only to the data of your choosing.

These kinds of

experimental blockchain technologies will require cautious and

careful experimentation worth investing in. But the goal shouldn't

be "hyper growth" and fast returns on those investments.

A couple months ago, I discovered another use for blockchain and a project that might be ready for prime time.

A collective of

developers and journalists are launching a radical

blockchain experiment called 'Civil.' To the average reader, 'Civil' will look like any other reputable news website. On the back end, however, articles will be archived on the blockchain so no publisher could ever remove them.

It will also have its own token economy in which consumers can participate, giving them the opportunity to help decide how this news platform is run and enforce strict journalistic standards.

'Civil' tokens will, in theory, end the need for clickbait headlines that can lead to fake news and shoddy reporting.

To entice readers to 'Civil,' its founders have recruited and given grants to a group of veteran journalists referred to as the "First Fleet," which includes me and my business partner.

We'll be documenting

whether the experiment works on

our new podcast.

If consumers think big

change is possible and have the chance to better understand the

mechanics behind that change, more of them will support worthy

experimental endeavors.

The collective philosophy behind the blockchain may be the path to making that happen.

|