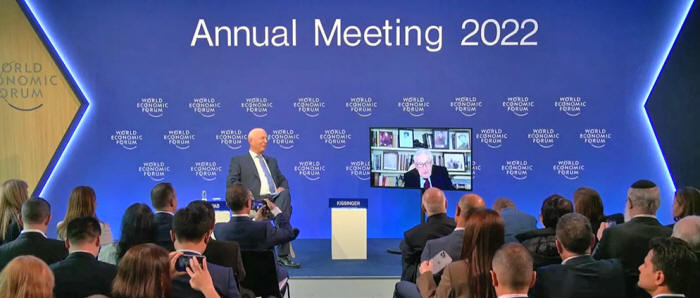

Klaus Schwab:

[00:00:02] Hello, Dr. Kissinger. Greetings from Geneva - I should

say from Davos. Do you hear us?

Henry Kissinger: [00:00:13] Yes, I hear you very well.

Klaus Schwab: [00:00:15] You know, you have here a great

assembly.

Everybody is interested in hearing your views. And I

don't have to introduce you, Dr. Kissinger. I just would like to

mention that I met you when I was at Harvard over 50 years ago.

And actually, you came to Davos the first time. It was in

(1980), so over 40 years ago. And I looked at your speech, which

you gave in 1980, and I just want to quote one or two things.

In your speech, you focused and I quote:

"It's a constantly

changing world."

Does it sound familiar?

And you said, and I

quote:

"The age of global interdependence."

End of quote.

And you warned of, I quote,

"a delusion of confidence in classic

models, a challenge to the system."

And you concluded your

speech by saying all of those changes are global and would make

ours a period of turmoil, even apart from any specific challenge

that we have to face.

1980, and, wow, we are 42 years later. And

of course, we are very keen to hear how you assess the situation

of today.

And I had the pleasure to visit you just some weeks

ago. And we have chosen, as I mentioned to you at that time,

history at a turning point.

We are really at a turning point. And this is not a speech.

This is a conversation of, I would

say, a young student and an experienced professor.

So, my first

question to you, Henry, is if you listen to the theme "history

at a turning point," would you describe the new world which may

arise after this turning point, which we are living through at

this moment?

Henry Kissinger: [00:02:59] Let me thank you for letting me

return to Davos, because it is such a crucial forum for the

exchange of ideas all over the world.

But the outcome of this

turning point - it's not yet obvious, because there are a number

of issues which are still under consideration within the realm

of the decision-makers and of course, many evolutions that are

going on that will affect the outcome.

Let me sketch the issues.

The most vivid at the moment is the

war in Ukraine, and the outcome of that war, both in the

military and political sense, will affect relations between

groupings of countries, which I will mention in a minute.

And

the outcome of any war and the peace settlement, and the nature

of that peace settlement - it will determine whether the

combatants remain permanent adversaries, or whether it is

possible to fit them into an international framework.

About eight years ago, when the idea of membership of Ukraine in

NATO came up, I wrote an article in which I said that the ideal

outcome would be if Ukraine could be constituted as a neutral

kind of state, as a bridge between Russia and Europe. Rather

than, it's the front line of groupings within Europe.

I think

that opportunity is now... does not now exist in the same manner,

but it could still be conceived as an ultimate objective.

In my

view, movement towards negotiations and negotiations on peace

need to begin in the next two months so that the outcome of the

war should be outlined.

But before it could create upheaval and

tensions that will be ever... harder to overcome, particularly

between the eventual relationship of Russia, Georgia and of

Ukraine towards Europe.

Ideally, the dividing line should return

the status quo ante.

I believe to join the war beyond Poland

would draw... turn it into a war and not about the freedom of

Ukraine, which has been undertaken with great cohesion by NATO,

but into against Russia itself and so, that seems to me to be

the dividing line that it is just impossible to define.

It will

be difficult for anybody to gauge of that.

Modifications of that

may occur during the negotiations, which of course, have not yet

been established, but which should begin to be the return of the

major participants as the war develops, and I have given an

outline of a possible military outcome.

But would like to keep

in mind that any modifications of that could complicate the

negotiations in which Ukraine has a right to be a significant

participant, but in which one hopes that they match the heroism

that they have shown in the war with wisdom for the balance in

Europe and in the world at large - a relationship that will

develop as a result of this war, between Ukraine, which will be

probably the strongest conventional power on the continent, and

the rest of Europe will develop over a period of time.

But one has to look both at the relationship of Europe to Russia

over a longer period and in a manner that is separated from the

existing leadership whose status, however, will be affected

internally over a period of time by its performance in

this period.

Looked at from a long-term point of view, Russia

has been, for 400 years, an essential part of Europe, and

European policy over that period of time has been affected,

fundamentally, by its European assessment of the role of Russia.

Sometimes in an observing way, but on a number of occasions as

the guarantor, or the instrument, by which the European balance

could be re-established.

Current policy should keep in mind the

restoration of this role is important to develop, so that

Russia

is not driven into a permanent alliance with China.

But European

relations with it are not the only key element of this

[unintelligible].

China and United States, we know that in the next years have to

come to some definition of how to conduct the long-term

relationship of countries, it depends on their strategic

capacities, but also on their interpretation of these

capacities.

In recent years, China and the United States evolved

into a relationship that is unique in each side's history. That

is that they, from the point of view of strategic potential,

they are the greatest threat to each other - in fact, the only

military threat that each side needs to deal with continuously.

And so the challenge, the period in which I was involved in the

creation of this relationship, in which it was thought that a

period of permanent collaboration might emerge of the two

countries becoming [unintelligible] has been partly jeopardized

and for the period probably terminated by the growth in the

strategic and technical competence of each other.

So on that

level, there is an inherent adversarial aspect.

The challenge is

whether this adversarial aspect can be mitigated and

progressively eased by the diplomacy that both sides conduct and

it cannot be done unilaterally by one side.

So, both sides have

to come to the conviction that some easing of the political

relationship is essential because they are in a position that

has never existed before - plainly, that a conflict with modern

technology, conducted in the absence of any preceding arms

control negotiations, so they have no established criteria of

limitations, will be a catastrophe for mankind.

Whatever, their differences are within the context of historical politics,

the leaders have an obligation to prevent this and ensure, at a

minimum, permanent consultations, serious consultations on the

subject, legal gameplays on a permanent basis.

And then it's an

evolution of this.

Of course, there are many unfinished periods in the future of

world. The emergence of additional nuclear powers, of which the

most urgent is the rise of Iran and the consequent divisions in

the Middle East.

And as in the period directly affected by the

Ukrainian issue, but affected by the balance that will emerge,

the rise of countries like India and Brazil and other countries,

will have to be integrated into an international system.

They

seem to me to be the key issues, together with the fact that the

Ukraine conflict has produced a rupture in the economic

arrangements that have been made in the period before, so that

the definition and operation of a global system will have to be

reconsidered.

It is these challenges I put forward as an analogy, but I

believe they must be overcome, if we not going to live in an

increasingly confrontational and chaotic world.

Klaus Schwab: [00:19:02] Thank you very much, Dr. Kissinger, for

this state of the world description.

We have, and I know he's

not prepared for it, but we have here someone sitting whom I

most admire also for his ideas, and he just has also published a

very significant book.

So, Graham Allison, would you be ready to

comment - and we need the microphone - could you be ready to

comment and maybe ask also, Dr. Kissinger, a final question.

What is prodding in your mind? But first, it would be

interesting to have your comments.

Graham Allison: [00:19:55] Thank you very much.

Henry Kissinger: [00:19:57] I didn't get the name.

Graham Allison: [00:20:00] Your oldest student.

Klaus Schwab: [00:20:02] Graham Allison.

Henry Kissinger: [00:20:06] Oh Graham Allison, yes.

Graham Allison: [00:20:13] I think Henry often refers to me as

his oldest student and course assistant, and I tell him that's

because I've been the slowest learner.

So, Henry, you're looking

great.

Though, Henry was supposed to be having a 99th birthday

party tonight in New York, but the circumstances didn't permit.

So I can see you're dressed up for the party, in any case and

I'm sorry I'm missing you there, but it's good to see you here.

Henry, you hear overview, was as always wonderful. And I think

Klaus did a good job in reminding us of the 1980 remarks where

we can hear echoes.

In 1980, though, China hardly figured in the

picture the way it does today.

So, as you look at the

relationship between the US and China, which as you say, is

inevitably inherently going to be rivalrous and adversarial, but

at the same time, if unmanaged, may and in a catastrophic war.

And as we watch what's happening in Taiwan and just to be timely

in terms of the news, the comment of President

Biden yesterday

in Japan about Taiwan - you and I talked about this before - I

think that seems to be about the fastest path to a general full

scale war between the U.S. and China.

So, I wonder how you are

thinking about Taiwan in the context of the need for the

constraints and rules of the road that you described the

necessity for, but that we now see the absence of.

Klaus Schwab: [00:22:25] Henry, do you want to respond?

Henry Kissinger: [00:22:29] It's been an unexpected pleasure to

see Graham appear and to put me a question. He was my student

and he is my friend and we have sewn along parallel lines over

many decades.

I negotiated the understanding on Taiwan at the very beginning

of the US-Chinese relationship.

There had been hundreds of

meetings on the subject between Chinese and American diplomat,

and they always ended on the first day because the Chinese

demanded the immediate turnover of Taiwan, and we insisted on

the continuation of the use of [unintelligible] methods of

achieving this objective.

So, I will not go through the process

of which it was achieved, but my understanding of the agreement

has been that the United States would uphold the principle of

one China, that we would now exist on a two-China solution, and

the Western world was prepared to live with a long period in

which this process would work itself out, and in which it was

always understood that the United States was opposed

[unintelligible] a military solution to that problem.

I believe

that these principles have enabled Taiwan to develop for 50

years as a democratic system.

And I think it is essential that these principles be maintained,

and the United States should not by subterfuge or a gradual

process, develop something of a two-China solution, but that

China will continue to exercise patience that has been exercised

up to now.

A direct confrontation should be avoided, and Taiwan cannot be

the core of the negotiations between China and the United

States.

For the core of the negotiations, it is important that

the United States and China discuss principles that affect the

adversarial relationship, and that permit at least some scope

for cooperative efforts.

The Taiwan issue will no disappear, but

as the direct subject of confrontation and adversarial conduct

it is bound to lead to situation that may mutate into the

military field, which is against the world interest and against

the long-term interest of China and the United States.

These are the causes I address to my friends in the American

government, but also to the friends that over the years I have

had an opportunity with on the Chinese side.

So, it is important

to the overall needs of the world for the United States and

China to mitigate their adversarial relationship by recognition

that, if a World War 1 type situation were to arise, of sliding

into a conflict, the consequences will be more dire than they

were then.

So, how to manage between an existing adversarial relationship

and the need for cooperation in the economic sense and

[unintelligible] is a big challenge for both governments, and it

will be affected [unintelligible] because China will have to re-analyze

its relationship with its established with Russia, because it

could not have expected when it was made that it would evolve in

the direction that it has.

And it will also be important for the

United States to go beyond its assessments of adversarial

relations and to some concept of a world order in which the

United States and China, partly due to the evolution of

economies and partly due to the evolution of ideologies, in an

ugly confrontation, and to turn it into something that is

compatible with world order.

Klaus Schwab: [00:30:44] Thank you. Thank you.

And we are coming

to an end of our session, and it was fascinating to hear your

still very visionary perspectives and to hear from you. Thank

you very much.

I have a very unusual idea. You may forgive for me, but as we

have heard also from Graham, Henry is celebrating his 99th

birthday this week.

So let's say all together: Happy birthday to

you Henry.

Audience: Happy birthday to you Henry.

Klaus Schwab: All the best and thank you. So, we have

one minute.

And I would I would like to use this minute because

Graham, you have written this book - keep the microphone Graham

- you have written this book, arguing that if you take

historical examples, a war between a competition which may end

in a war, let's put it in this way, between the US and China is

inevitable.

May you just in some very few sentences share with the

audience.

Do you still think this case is coming?

Graham Allison: [00:32:38] So, basically, I didn't come to

speak.

I came to listen to Henry. But this is an idea that

emerged over some years.

Henry uses history to help inform and illuminate the present and

the choices and the challenges.

In my book

The Thucydides Trap,

I look at the last 500 years, we find 16 cases in which a

rapidly rising power like Athens in classical Greece or Germany

at the beginning of the 20th century, challenges a colossal

ruling power like Sparta or Great Britain or the US today.

So,

12 of those 16 end in war - so war is not inevitable, just it's

been the way that things have happened.

Several people since I've gotten there have asked me:

"Well, so

what would Thucydides say now?" since this book was written five

years ago, just as Trump become President.

And I think he would say both the rising power and the ruling

power seem right on script, almost as if each is competing to

see which can better exemplify the typical rising power and

typical ruling power.

So, (Thucydides) is sitting on the edge of

his seat, anticipating the greatest war of all time.

Klaus Schwab: [00:34:15] If you follow the advice of Henry that

would be the-

Graham Allison: [00:34:23] The fifth of the four that escaped

Thucydides' trap - rather than the thirteen or the twelve that

led to catastrophic outcomes.

Klaus Schwab: [00:34:34] So Henry, you have given us very

valuable advice and thank you again and thank you also Graham.

Thank you Henry.

We wish you all the best, and this concludes

our session.