|

by Swiss Propaganda Research

June 2016

from SPR

Website

english translation by

Terje Maloy

March

03, 2019

from

InformationClearingHouse

Website

Original German version

Spanish

version

Italian

version

It is one of the most important aspects of our media system - and

yet hardly known to the public:

most of the international news

coverage in Western media is provided by only three global news

agencies based in New York, London and Paris.

The key role played by these agencies means that Western media often

report on the same topics, even using the same wording.

In addition, governments,

military and intelligence services use these global news agencies as

multipliers to spread their messages around the world.

A study of the Syria war coverage by nine leading European

newspapers clearly illustrates these issues:

-

78% of all

articles are based in whole or in part on agency reports,

yet 0% on investigative research

-

moreover, 82% of

all opinion pieces and interviews are in favor of the US and

NATO intervention, while propaganda is attributed

exclusively to the opposite side

Introduction -

"Something strange"

"How does the

newspaper know what it knows?"

The answer to this

question is likely to surprise some newspaper readers:

"The main source of

information is stories from news agencies. The almost

anonymously operating news agencies are in a way the key to

world events.

So what are the names

of these agencies, how do they work and who finances them? To

judge how well one is informed about events in East and West,

one should know the answers to these questions."

(Höhne

1977, p. 11)

A Swiss media researcher

points out:

"The news agencies

are the most important suppliers of material to mass media.

No daily media outlet

can manage without them. So the news agencies influence our

image of the world; above all, we get to know what they have

selected."

(Blum 1995, p. 9)

In view of their

essential importance, it is all the more astonishing that these

agencies are hardly known to the public:

"A large part of

society is unaware that news agencies exist at all … In fact,

they play an enormously important role in the media market. But

despite this great importance, little attention has been paid to

them in the past."

(Schulten-Jaspers

2013, p. 13)

Even the head of a news

agency noted:

"There is something

strange about news agencies. They are little known to the

public. Unlike a newspaper, their activity is not so much in the

spotlight, yet they can always be found at the source of the

story."

(Segbers

2007, p. 9)

"The Invisible

Nerve Center of the Media System"

So what are the names of these agencies that are "always at the

source of the story"?

There are now only three

global agencies left:

-

The American

Associated Press (AP)

with over 4000 employees worldwide. The AP belongs to US

media companies and has its main editorial office in New

York. AP news is used by around 12,000 international media

outlets, reaching more than half of the world's population

every day.

-

The

quasi-governmental French Agence France-Presse (AFP)

based in Paris and with around 4000 employees. The AFP sends

over 3000 stories and photos every day to media all over the

world.

-

The British

agency

Reuters

in London, which is privately owned and employs

just over 3000 people. Reuters was acquired in 2008 by

Canadian media entrepreneur Thomson - one of the 25 richest

people in the world - and merged into Thomson Reuters,

headquartered in New York.

In addition, many

countries run their own news agencies.

However, when it comes to

international news, these usually rely on the three global agencies

and simply copy and translate their reports.

The three global news agencies Reuters, AFP and AP, and the three

national agencies of the German-speaking countries of,

-

Austria (APA)

-

Germany (DPA)

-

Switzerland (SDA)

Wolfgang Vyslozil,

former managing director of the Austrian APA, described the key role

of news agencies with these words:

"News agencies are

rarely in the public eye. Yet they are one of the most

influential and at the same time one of the least known media

types.

They are key

institutions of substantial importance to any media system. They

are the invisible nerve center that connects all parts of this

system

(Segbers

2007, p.10)

Small

abbreviation, great effect

However, there is a simple reason why the global agencies, despite

their importance, are virtually unknown to the general public.

To quote a Swiss media

professor:

"Radio and television

usually do not name their sources, and only specialists can

decipher references in magazines."

(Blum 1995, P. 9)

The motive for this

discretion, however, should be clear: news outlets are not

particularly keen to let readers know that they haven't researched

most their contributions themselves.

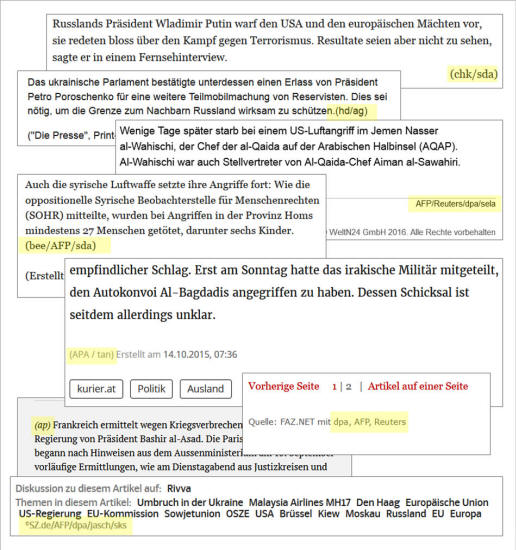

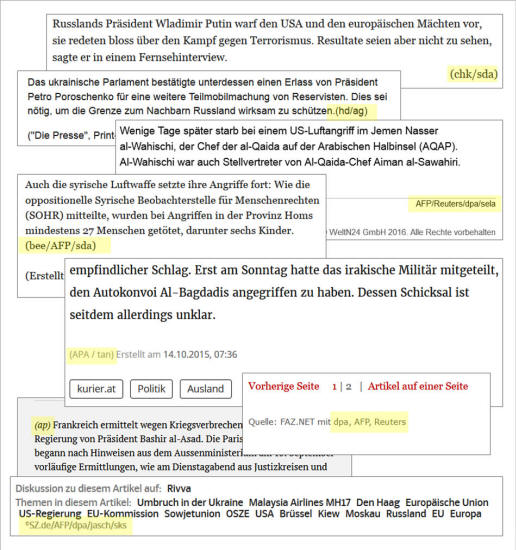

The following figure shows some examples of source tagging in

popular German-language newspapers. Next to the agency abbreviations

we find the initials of editors who have edited the respective

agency report.

News agencies as sources in newspaper articles

Occasionally,

newspapers use agency material

but do not label it at all.

A study in 2011 from the

Swiss Research Institute for the Public Sphere and Society at the

University of Zurich came to the following conclusions (FOEG 2011):

"Agency contributions

are exploited integrally without labeling them, or they are

partially rewritten to make them appear as an editorial

contribution.

In addition, there is

a practice of 'spicing up' agency reports with little effort;

for example, visualization techniques are used:

unpublished

agency reports are enriched with images and graphics and

presented as comprehensive reports."

The agencies play a

prominent role not only in the press, but also in private and public

broadcasting.

This is confirmed by

Volker Braeutigam, who worked for the German state broadcaster

ARD for ten years and views the dominance of these agencies

critically:

"One fundamental

problem is that the newsroom at ARD sources its information

mainly from three sources:

the news agencies

DPA/AP, Reuters and AFP: one German/American, one British

and one French.

The editor working on

a news topic only needs to select a few text passages on the

screen that he considers essential, rearrange them and glue them

together with a few flourishes."

Swiss Radio and

Television (SRF), too, largely bases itself on reports from these

agencies.

Asked by viewers why a

peace march in Ukraine was not reported, the editors

said:

"To date, we have not

received a single report of this march from the independent

agencies Reuters, AP and AFP."

In fact, not only the

text, but also the images, sound and video recordings that we

encounter in our media every day, are mostly from the very same

agencies.

What the uninitiated

audience might think of as contributions from their local newspaper

or TV station, are actually copied reports from New York, London and

Paris.

Some media have even gone a step further and have, for lack of

resources, outsourced their entire foreign editorial office to an

agency. Moreover, it is well known that many news portals on the

internet mostly publish agency reports (see e.g., Paterson 2007,

Johnston 2011, MacGregor 2013).

In the end, this dependency on the global agencies creates a

striking similarity in international reporting:

from Vienna to

Washington, our media often report the same topics, using many

of the same phrases - a phenomenon that would otherwise rather

be associated with "controlled media" in authoritarian states.

The following graphic

shows some examples from German and international publications. As

you can see, despite the claimed objectivity, a slight

(geo-)political bias sometimes creeps in.

"Putin threatens", "Iran provokes",

"NATO

concerned", "Assad stronghold":

Similarities in content and wording

due to

reports by global news agencies.

The role of

correspondents

Much of our media does not have own foreign correspondents, so they

have no choice but to rely completely on global agencies for foreign

news.

But what about the big

daily newspapers and TV stations that have their own international

correspondents?

In German-speaking

countries, for example, these include newspapers such,

-

NZZ

-

FAZ

-

Sueddeutsche

Zeitung

-

Welt,

...and public

broadcasters.

First of all, the size ratios should be kept in mind:

while the global agencies

have several thousand employees worldwide, even the Swiss newspaper

NZZ, known for its international reporting, maintains only 35

foreign correspondents (including their business correspondents).

In huge countries

such as China or India, only one correspondent is stationed; all

of South America is covered by only two journalists, while in

even larger Africa no-one is on the ground permanently.

Moreover, in war zones, correspondents rarely venture out. On

the Syria war, for example, many journalists "reported" from

cities such as Istanbul, Beirut, Cairo or even from Cyprus.

In addition, many

journalists lack the language skills to understand local people

and media.

How do correspondents

under such circumstances know what the "news" is in their region of

the world?

The main answer is once

again:

from global agencies.

The Dutch Middle East

correspondent Joris Luyendijk has impressively described how

correspondents work and how they depend on the world agencies in his

book "People

Like Us - Misrepresenting the Middle East":

"I'd imagined

correspondents to be historians-of-the-moment.

When something

important happened, they'd go after it, find out what was going

on, and report on it. But I didn't go off to find out what was

going on; that had been done long before. I went along to

present an on-the-spot report.

The editors in the Netherlands called when something happened,

they faxed or emailed the press releases, and I'd retell them in

my own words on the radio, or rework them into an article for

the newspaper.

This was the reason

my editors found it more important that I could be reached in

the place itself than that I knew what was going on. The news

agencies provided enough information for you to be able to write

or talk you way through any crisis or summit meeting.

That's why you often come across the same images and stories if

you leaf through a few different newspapers or click the news

channels.

Our men and women in London, Paris, Berlin and Washington

bureaus - all thought that wrong topics were dominating the news

and that we were following the standards of the news agencies

too slavishly.

The common idea about correspondents is that they 'have the

story', but the reality is that the news is a conveyor belt in a

bread factory.

The correspondents

stand at the end of the conveyor belt, pretending we've baked

that white loaf ourselves, while in fact all we've done is put

it in its wrapping.

Afterwards, a friend asked me how I'd managed to answer all the

questions during those cross-talks, every hour and without

hesitation. When I told him that, like on the TV-news, you knew

all the questions in advance, his e-mailed response came packed

with expletives.

My friend had

realized that, for decades, what he'd been watching and

listening to on the news was pure theatre."

(Luyendjik 2009, p. 20-22, 76, 189)

In other words, the

typical correspondent is in general not able to do independent

research, but rather deals with and reinforces those topics that are

already prescribed by the news agencies - the notorious "mainstream

effect".

In addition, for cost-saving reasons many media outlets nowadays

have to share their few foreign correspondents, and within

individual media groups, foreign reports are often used by several

publications - none of which contributes to diversity in reporting.

"What the

agency does not report, does not take place"

The central role of news agencies also explains why, in geopolitical

conflicts, most media use the same original sources.

In the Syrian war, for

example, the "Syrian

Observatory for Human Rights" - a dubious one-man

organization based in London - featured prominently.

The media rarely inquired

directly at this "Observatory", as its operator was in fact

difficult to reach, even for journalists.

Rather, the "Observatory" delivered its stories to global agencies,

which then forwarded them to thousands of media outlets, which in

turn "informed" hundreds of millions of readers and viewers

worldwide.

The reason why the

agencies, of all places, referred to this strange "Observatory" in

their reporting - and who really financed it - is a question that

was rarely asked.

The former chief editor of the German news agency DPA, Manfred

Steffens, therefore states in his book "The Business of

News":

"A news story does

not become more correct simply because one is able to provide a

source for it. It is indeed rather questionable to trust a news

story more just because a source is cited.

Behind the protective

shield such a 'source' means for a news story, some people are

quite inclined to spread rather adventurous things, even if they

themselves have legitimate doubts about their correctness.

The responsibility,

at least morally, can always be attributed to the cited source."

(Steffens 1969, p. 106)

Dependence on global

agencies is also a major reason why media coverage of geopolitical

conflicts is often superficial and erratic, while historic

relationships and background are fragmented or altogether absent.

As put by Steffens:

"News agencies

receive their impulses almost exclusively from current events

and are therefore by their very nature ahistoric. They are

reluctant to add any more context than is strictly required."

(Steffens 1969, p. 32)

Finally, the dominance of

global agencies explains why certain geopolitical issues and events

- which often do not fit very well into the US/NATO narrative or are

too "unimportant" - are not mentioned in our media at all:

if the agencies do

not report on something, then most Western media will not be

aware of it.

As pointed out on the

occasion of the 50th anniversary of the German DPA:

"What the agency does

not report, does not take place."

(Wilke

2000, p. 1)

"Adding

questionable stories"

While some topics do not appear at all in our media, other topics

are very prominent - even though they shouldn't actually be:

"Often the mass media

do not report on reality, but on a constructed or staged

reality.

Several studies have

shown that the mass media are predominantly determined by PR

activities and that passive, receptive attitudes outweigh

active-researching ones."

(Blum 1995, p. 16)

In fact, due to the

rather low journalistic performance of our media and their high

dependence on a few news agencies, it is easy for interested parties

to spread propaganda and disinformation in a supposedly respectable

format to a worldwide audience.

DPA editor Steffens

warned of this danger:

"The critical sense

gets more lulled the more respected the news agency or newspaper

is.

Someone who wants to

introduce a questionable story into the world press only needs

to try to put his story in a reasonably reputable agency, to be

sure that it then appears a little later in the others.

Sometimes it happens

that a hoax passes from agency to agency and becomes ever more

credible."

(Steffens 1969, p. 234)

Among the most active

actors in "injecting" questionable geopolitical news are the

military and defense ministries.

For example, in 2009, the

head of the American news agency AP, Tom Curley, made public

that the Pentagon employs more than 27,000 PR specialists who, with

a budget of nearly $ 5 billion a year, are working the media and

circulating targeted manipulations.

In addition, high-ranking

US generals had threatened that they would "ruin" the AP and him if

the journalists reported too critically on the US military.

Despite - or because of? - such threats our media regularly publish

dubious stories sourced to some unnamed "informants" from "US

defense circles".

Ulrich Tilgner, a veteran Middle East correspondent for

German and Swiss television, warned in 2003, shortly after the Iraq

war, of acts of deception by the military and the role played by the

media:

"With the help of the

media, the military determine the public perception and use it

for their plans.

They manage to stir

expectations and spread scenarios and deceptions. In this new

kind of war, the PR strategists of the US administration fulfill

a similar function as the bomber pilots.

The special

departments for public relations in the Pentagon and in the

secret services have become combatants in the information war.

The US military

specifically uses the lack of transparency in media coverage for

their deception maneuvers.

The way they spread

information, which is then picked up and distributed by

newspapers and broadcasters, makes it impossible for readers,

listeners or viewers to trace the original source.

Thus, the audience

will fail to recognize the actual intention of the military."

(Tilgner

2003, p. 132)

What is known to the US

military, would not be foreign to US intelligence services.

In a remarkable report by

British Channel 4, former CIA officials and a Reuters correspondent

spoke candidly about the systematic dissemination of propaganda and

misinformation in reporting on geopolitical conflicts:

Former CIA officer

and whistleblower

John Stockwell said of his work

in the Angolan war,

"The basic theme

was to make it look like an [enemy] aggression in Angola.

So any kind of

story that you could write and get into the media anywhere

in the world, that pushed that line, we did. One third of my

staff in this task force were covert action, were

propagandists, whose professional career job was to make up

stories and finding ways of getting them into the press.

The editors in

most Western newspapers are not too skeptical of messages

that conform to general views and prejudices.

So we came up

with another story, and it was kept going for weeks. [But]

it was all fiction."

Fred Bridgland looked back on

his work as a war correspondent for the Reuters agency:

"We based our

reports on official communications.

It was not until

years later that I learned a little CIA disinformation

expert had sat in the US embassy, in Lusaka (Zambia) and

composed that communiqué, and it bore no relation at all to

truth.

Basically, and to

put it very crudely, you can publish any old crap and it

will get newspaper room."

And former CIA

analyst

David MacMichael described his

work in the

Contra War in Nicaragua with

these words:

"They said our

intelligence of Nicaragua was so good that we could even

register when someone flushed a toilet. But I had the

feeling that the stories we were giving to the press came

straight out of the toilet."

(Hird

1985)

Of course, the

intelligence services also have a large number of

direct contacts in our media, which

can be "leaked" information to if necessary.

But without the central

role of the global news agencies, the worldwide synchronization of

propaganda and disinformation would never be so efficient.

Through this "propaganda multiplier", dubious stories from PR

experts working for governments, military and intelligence services

reach the general public more or less unchecked and unfiltered.

The journalists refer to

the news agencies and the news agencies refer to their sources.

Although they often

attempt to point out uncertainties with terms such as "apparent",

"alleged" and the like - by then the rumor has long been spread to

the world and its effect taken place.

The Propaganda Multiplier:

Governments, military and intelligence services

using global news agencies to disseminate

their messages to a worldwide audience.

As The New

York Times reported...

In addition to global news agencies, there is another source that is

often used by media outlets around the world to report on

geopolitical conflicts, namely the major publications in Great

Britain and the US.

For example, news outlets like the New York Times or BBC have up to

100 foreign correspondents and other external employees.

However, Middle East

correspondent Luyendijk points out:

"Dutch news teams, me

included, fed on the selection of news made by quality media

like CNN, the BBC, and the New York Times.

We did that on the

assumption that their correspondents understood the Arab world

and commanded a view of it - but many of them turned out not to

speak Arabic, or at least not enough to be able to have a

conversation in it or to follow the local media.

Many of the top dogs

at CNN, the BBC, the Independent, the Guardian, the New Yorker,

and the NYT were more often than not dependent on assistants and

translators."

(Luyendijk p. 47)

In addition, the sources

of these media outlets are often not easy to verify ("military

circles", "anonymous government officials", "intelligence officials"

and the like) and can therefore also be used for the dissemination

of propaganda.

In any case, the

widespread orientation towards the Anglo-Saxon publications leads to

a further convergence in the geopolitical coverage in our media.

The following figure shows some examples of such citation based on

the Syria coverage of the largest daily newspaper in Switzerland,

Tages-Anzeiger.

The articles are all from

the first days of October 2015, when Russia for the first time

intervened directly in the Syrian war (US/UK sources are

highlighted):

Frequent citation of British and US media,

exemplified by the Syria war coverage

of

Swiss daily newspaper Tages-Anzeiger

in

October 2015.

The desired narrative

But why do journalists in our media not simply try to research and

report independently of the global agencies and the Anglo-Saxon

media?

Middle East correspondent

Luyendijk describes his experiences:

"You might suggest

that I should have looked for sources I could trust.

I did try, but

whenever I wanted to write a story without using news agencies,

the main Anglo-Saxon media, or talking heads, it fell apart.

Obviously I, as a correspondent, could tell very different

stories about one and the same situation.

But the media could

only present one of them, and often enough, that was exactly the

story that confirmed the prevailing image."

(Luyendijk

p.54ff)

Media researcher Noam

Chomsky has described this effect in his essay "What

makes the Mainstream Media Mainstream" as follows:

"If you leave the

official line, if you produce dissenting reports, then you will

soon feel this. There are many ways to get you back in line

quickly.

If you don't follow

the guidelines, you will not keep your job long.

This system works

pretty well, and it reflects established power structures."

(Chomsky 1997)

Nevertheless, some of the

leading journalists continue to believe that nobody can tell them

what to write.

How does this add up?

Media researcher Chomsky

clarifies the apparent

contradiction:

"[T]he point is that

they wouldn't be there unless they had already demonstrated that

nobody has to tell them what to write because they are going say

the right thing.

If they had started

off at the Metro desk, or something, and had pursued the wrong

kind of stories, they never would have made it to the positions

where they can now say anything they like.

They have been

through the socialization system."

(Chomsky 1997)

Ultimately, this

"socialization process" leads to a journalism that generally no

longer independently researches and critically reports on

geopolitical conflicts (and some other topics), but seeks to

consolidate the desired narrative through appropriate editorials,

commentary, and interviewees.

Conclusion -

The "First Law of Journalism"

Former AP journalist Herbert Altschull called it the First

Law of Journalism:

"In all press

systems, the news media are instruments of those who exercise

political and economic power.

Newspapers,

periodicals, radio and television stations do not act

independently, although they have the possibility of independent

exercise of power."

(Altschull 1984/1995, p. 298)

In that sense, it is

logical that our traditional media - which are predominantly

financed by advertising or the state - represent the geopolitical

interests of the transatlantic alliance, given that both the

advertising corporations as well as the states themselves are

dependent on the US dominated transatlantic economic and security

architecture.

In addition, our leading media and their key people are - in the

spirit of Chomsky's "socialization" - often themselves part of the

networks of the transatlantic elite.

Some of the most

important institutions in this regard include,

See in-depth study of

these networks:

The American Empire and its Media.

Indeed, most well-known publications basically may be seen as

"establishment media".

This is because, in the

past, the freedom of the press was rather theoretical, given

significant entry barriers such as,

...and other

restrictions.

It was only due to the Internet that Altschull's First Law has been

broken to some extent.

Thus, in recent years a

high-quality, reader-funded journalism has emerged, often

outperforming traditional media in terms of critical reporting. Some

of these "alternative" publications already reach a very large

audience, showing that the "mass" does not have to be a problem for

the quality of a media outlet.

Nevertheless, up to now the traditional media has been able to

attract a solid majority of online visitors, too. This, in turn, is

closely linked to the hidden role of news agencies, whose

up-to-the-minute reports form the backbone of most news portals.

Will "political and economic power", according to Altschull's Law,

retain control over the news, or will "uncontrolled" news change the

political and economic power structure?

The coming years will

show...

Case study -

Syria war coverage

As part of a case study,

the Syria war coverage of nine

leading daily newspapers from Germany, Austria and Switzerland were

examined for plurality of viewpoints and reliance on news agencies.

The following newspapers

were selected:

-

For Germany: Die

Welt, Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ), and Frankfurter Allgemeine

Zeitung (FAZ)

-

For Switzerland:

Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ), Tagesanzeiger (TA), and Basler

Zeitung (BaZ)

-

For Austria:

Standard, Kurier, and Die Presse

The investigation period

was defined as October 1 to 15, 2015, i.e. the first two weeks after

Russia's direct intervention in the Syrian conflict.

The entire print and

online coverage of these newspapers was taken into account. Any

Sunday editions were not taken into account, as not all of the

newspapers examined have such. In total, 381 newspaper articles met

the stated criteria.

In a first step, the articles were classified according to their

properties into the following groups:

-

Agencies: Reports

from news agencies (with agency code)

-

Mixed: Simple

reports (with author names) that are based in whole or in

part on agency reports

-

Reports:

Editorial background reports and analyzes

-

Opinions/Comments: Opinions and guest comments

-

Interviews:

interviews with experts, politicians etc.

-

Investigative:

Investigative research that reveals new information or

context

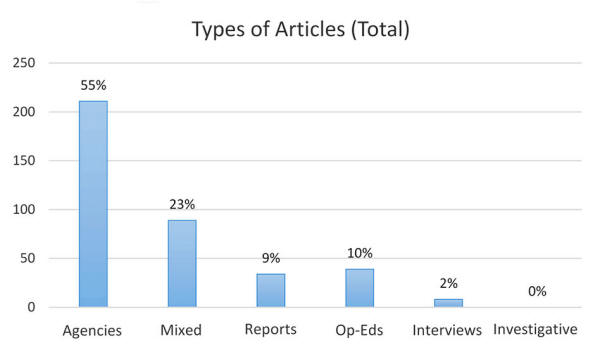

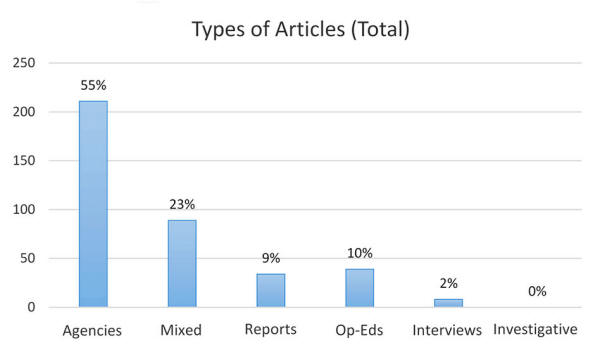

The following Figure 1

shows the composition of the articles for the nine newspapers

analyzed in total.

As can be seen,

-

55% of articles

were news agency reports

-

23% editorial

reports based on agency material

-

9% background

reports

-

10% opinions and

guest comments

-

2% interviews

-

0% based on

investigative research

Figure 1

Types of articles (total; n=381)

The pure agency texts - from short notices to the detailed reports -

were mostly on the Internet pages of the daily newspapers:

-

on the one hand,

the pressure for breaking news is higher than in the printed

edition

-

on the other

hand, there are no space restrictions

Most other types of

articles were found in both the online and printed editions; some

exclusive interviews and background reports were found only in the

printed editions.

All items were collected

only once for the investigation.

The following Figure 2 shows the same classification on a per

newspaper basis. During the observation period (two weeks), most

newspapers published between 40 and 50 articles on the Syrian

conflict (print and online).

In the German newspaper

Die Welt there were more (58), in the Basler Zeitung and the

Austrian Kurier, however, significantly less (29 or 33).

Depending on which newspaper, the share of agency reports is,

-

almost 50% (Welt,

Süddeutsche, NZZ, Basler Zeitung)

-

just under 60% (FAZ,

Tagesanzeiger)

-

60 to 70% (Presse,

Standard, Kurier)

Together with the

agency-based reports, the proportion in most newspapers is between

approx. 70% and 80%.

These proportions are

consistent with previous media studies (e.g., Blum 1995, Johnston

2011, MacGregor 2013, Paterson 2007).

In the background reports, the Swiss newspapers were leading (five

to six pieces), followed by Welt, Süddeutsche and Standard (four

each) and the other newspapers (one to three).

The background reports

and analyzes were in particular devoted to the situation and

development in the Middle East, as well as to the motives and

interests of individual actors (for example Russia, Turkey, the

Islamic State).

However, most of the commentaries were to be found in the German

newspapers (seven comments each), followed by Standard (five), NZZ

and Tagesanzeiger (four each).

Basler Zeitung did not

publish any commentaries during the observation period, but two

interviews. Other interviews were conducted by Standard (three) and

Kurier and Presse (one each).

Investigative research,

however, could not be found in any of the newspapers.

In particular, in the case of the three German newspapers, a

journalistically problematic blending of opinion pieces and reports

was noted.

Reports contained strong

expressions of opinion even though they were not marked as

commentary. The present study was in any case based on the article

labeling by the newspaper.

Figure 2

Types

of articles per newspaper

The following Figure 3 shows the breakdown of agency stories (by

agency abbreviation) for each news agency, in total and per country.

The 211 agency reports

carried a total of 277 agency codes (a story may consist of material

from more than one agency).

In total,

-

24% of agency

reports came from the AFP

-

about 20% each by

the DPA, APA and Reuters

-

9% of the SDA

-

6% of the AP

-

11% were unknown

(no labeling or blanket term "agencies")

In Germany, the DPA, AFP

and Reuters each have a share of about one third of the news

stories. In Switzerland, the SDA and the AFP are in the lead, and in

Austria, the APA and Reuters.

In fact, the shares of the global agencies AFP, AP and Reuters are

likely to be even higher, as the Swiss SDA and the Austrian APA

obtain their international reports mainly from the global agencies

and the German DPA cooperates closely with the American AP.

It should also be noted that, for historical reasons, the global

agencies are represented differently in different regions of the

world.

For events in Asia,

Ukraine or Africa, the share of each agency will therefore be

different than from events in the Middle East.

Figure 3

Share

of news agencies,

total

(n=277) and per country

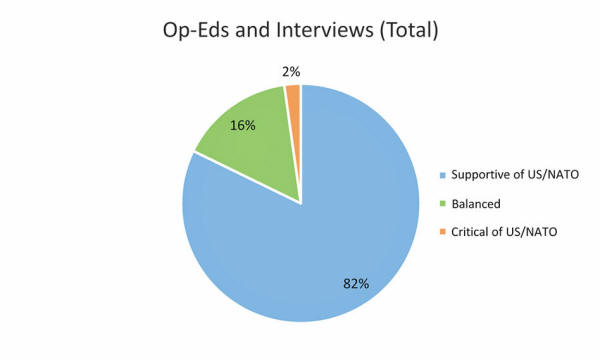

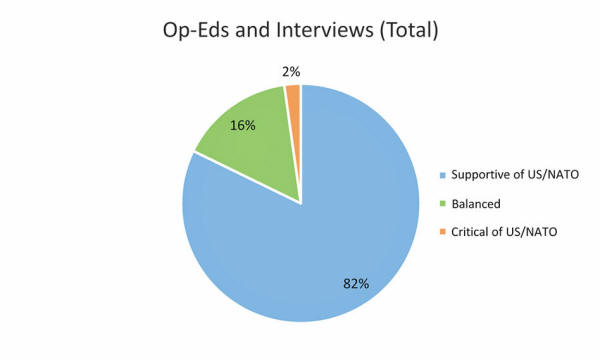

In the next step, central statements were used to rate the

orientation of editorial opinions (28), guest comments (10) and

interview partners (7) (a total of 45 articles).

As Figure 4 shows, 82% of

the contributions were generally US/NATO friendly, 16% neutral or

balanced, and 2% predominantly US/NATO critical.

The only predominantly US/NATO-critical contribution was an op-ed in

the Austrian Standard on October 2, 2015, titled:

"The strategy of

regime change has failed. A distinction between ‚good' and ‚bad'

terrorist groups in Syria makes the Western policy

untrustworthy."

Figure 4

Orientation of editorial opinions, guest comments,

and

interviewees (total; n=45).

The following Figure 5 shows the orientation of the contributions,

guest comments and interviewees, in turn broken down by individual

newspapers.

As can be seen, Welt,

Süddeutsche Zeitung, NZZ, Zürcher Tagesanzeiger and the Austrian

newspaper Kurier presented exclusively US/NATO-friendly opinion and

guest contributions.

This goes for FAZ too,

with the exception of one neutral/balanced contribution.

The Standard

brought four US/NATO friendly, three balanced/neutral, as well as

the already mentioned US/NATO critical opinion contributions.

Presse was the only one of the examined newspapers to predominantly

publish neutral/balanced opinions and guest contributions. The

Basler Zeitung published one US/NATO-friendly and one balanced

contribution.

Shortly after the

observation period (October 16, 2015), Basler Zeitung also published

an interview with the President of the Russian Parliament.

This would of course have

been counted as a contribution critical of the US/NATO.

Figure 5

Basic

orientation of opinion pieces

and

interviewees per newspaper

In a further analysis, a full-text keyword search for "propaganda"

(and word combinations thereof) was used to investigate in which

cases the newspapers themselves identified propaganda in one of the

two geopolitical conflict sides, USA/NATO or Russia (the participant

"IS/ISIS" was not considered).

In total, twenty such

cases were identified.

Figure 6 shows the

result:

-

in 85% of the

cases, propaganda was identified on the Russian side of the

conflict

-

in 15% the

identification was neutral or unstated

-

in 0% of the

cases propaganda was identified on the USA/NATO side of the

conflict

It should be noted that

about half of the cases (nine) were in the Swiss NZZ, which spoke of

Russian propaganda quite frequently,

"Kremlin propaganda"

"Moscow propaganda

machine"

"propaganda stories"

"Russian propaganda

apparatus" etc.,

...followed by German FAZ

(three), Welt and Süddeutsche Zeitung (two each) and the Austrian

newspaper Kurier (one).

The other newspapers did

not mention propaganda, or only in a neutral context (or in the

context of IS).

Figure 6

Attribution of propaganda

to

conflict parties (total; n=20).

Conclusion

In this case study, the geopolitical coverage in nine leading daily

newspapers from Germany, Austria and

Switzerland was examined for diversity and journalistic

performance using the example of the Syrian war.

The results confirm the high dependence on the global news agencies

(63 to 90%, excluding commentaries and interviews) and the lack of

own investigative research, as well as the rather biased commenting

on events in favor of the US/NATO side (82% positive; 2% negative),

whose stories were not checked by the newspapers for any propaganda.

Literature

Altschull, Herbert J.

(1984/1995): Agents of power. The media and public policy.

Longman, New York.

Becker, Jörg (2015): Medien im Krieg - Krieg in den Medien.

Springer Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden.

Blum, Roger et al. (Hrsg.) (1995): Die AktualiTäter.

Nachrichtenagenturen in der Schweiz. Verlag Paul Haupt, Bern.

Chomsky, Noam (1997): What Makes Mainstream Media Mainstream. Z

Magazine, MA. (PDF)

Forschungsinstitut für Öffentlichkeit und Gesellschaft der

Universität Zürich (FOEG) (2011): Jahrbuch Qualität der Medien,

Ausgabe 2011. Schwabe, Basel.

Gritsch, Kurt (2010): Inszenierung eines gerechten Krieges?

Intellektuelle, Medien und der "Kosovo-Krieg" 1999. Georg Olms

Verlag, Hildesheim.

Hird, Christopher (1985): Standard Techniques. Diverse Reports,

Channel 4 TV. 30. Oktober 1985. (Link)

Höhne, Hansjoachim (1977): Report über Nachrichtenagenturen.

Band 1: Die Situation auf den Nachrichtenmärkten der Welt. Band

2: Die Geschichte der Nachricht und ihrer Verbreiter. Nomos

Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden.

Johnston, Jane & Forde, Susan (2011): The Silent Partner: News

Agencies and 21st Century News. International Journal of

Communication 5 (2011), p. 195–214. (PDF)

Krüger, Uwe (2013): Meinungsmacht. Der Einfluss von Eliten auf

Leitmedien und Alpha-Journalisten - eine kritische

Netzwerkanalyse. Herbert von Halem Verlag, Köln.

Luyendijk, Joris (2015): Von Bildern und Lügen in Zeiten des

Krieges: Aus dem Leben eines Kriegsberichterstatters -

Aktualisierte Neuausgabe. Tropen, Stuttgart.

MacGregor, Phil (2013): International News Agencies. Global eyes

that never blink. In: Fowler-Watt/Allan (ed.): Journalism: New

Challenges. Centre for Journalism & Communication Research,

Bournemouth University. (PDF)

Mükke, Lutz (2014): Korrespondenten im Kalten Krieg. Zwischen

Propaganda und Selbstbehauptung. Herbert von Halem Verlag, Köln.

Paterson, Chris (2007): International news on the internet. The

International Journal of Communication Ethics. Vol 4, No 1/2

2007. (PDF)

Queval, Jean (1945): Première page, Cinquième colonne. Arthème

Fayard, Paris.

Schulten-Jaspers, Yasmin (2013): Zukunft der

Nachrichtenagenturen. Situation, Entwicklung, Prognosen. Nomos,

Baden-Baden.

Segbers, Michael (2007): Die Ware Nachricht. Wie

Nachrichtenagenturen ticken. UVK, Konstanz.

Steffens, Manfred [Ziegler, Stefan] (1969): Das Geschäft mit der

Nachricht. Agenturen, Redaktionen, Journalisten. Hoffmann und

Campe, Hamburg.

Tilgner, Ulrich (2003): Der inszenierte Krieg - Täuschung und

Wahrheit beim Sturz Saddam Husseins. Rowohlt, Reinbek.

Wilke, Jürgen (Hrsg.) (2000): Von der Agentur zur Redaktion.

Böhlau, Köln.

|