|

February 19, 2019 from AEON Website

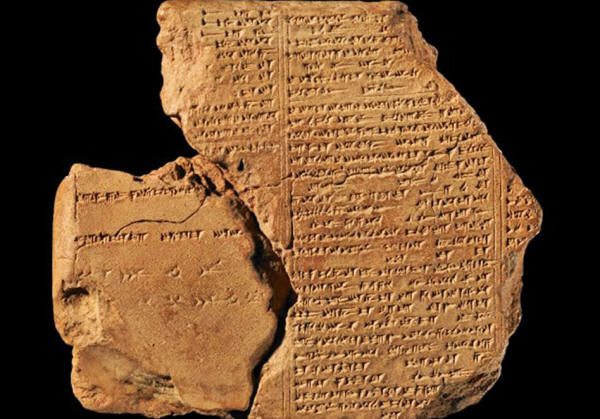

containing three columns of cuneiform inscription from tablet 6 of The Epic of Gilgamesh.

Courtesy the Trustees of the British Museum.

It tells the story of Gilgamesh, king of the city of Uruk. To curb his restless and destructive energy, the gods create a friend for him, Enkidu, who grows up among the animals of the steppe.

When Gilgamesh hears about this wild man, he orders that a woman named Shamhat be brought out to find him.

Shamhat seduces Enkidu, and the two make love for six days and seven nights, transforming Enkidu from beast to man. His strength is diminished, but his intellect is expanded, and he becomes able to think and speak like a human being.

Shamhat and Enkidu travel together to a camp of shepherds, where Enkidu learns the ways of humanity.

Eventually, Enkidu goes

to Uruk to confront Gilgamesh's abuse of power, and the two heroes

wrestle with one another, only to form a passionate friendship.

It began as a cycle of stories in the Sumerian language, which were then collected and translated into a single epic in the Akkadian language.

The earliest version of

the epic was written in a dialect called Old Babylonian, and

this version was later revised and updated to create another

version, in the Standard Babylonian dialect, which is the one

that most readers will encounter today.

Rather, Gilgamesh has to be recreated from hundreds of clay tablets that have become fragmentary over millennia.

The story comes to us as a tapestry of shards, pieced together by philologists to create a roughly coherent narrative (about four-fifths of the text have been recovered). The fragmentary state of the epic also means that it is constantly being updated, as archaeological excavations - or, all too often, illegal lootings - bring new tablets to light, making us reconsider our understanding of the text.

Despite being more than 4,000 years old, the text remains in flux, changing and expanding with each new finding.

The newest discovery is a tiny fragment that had lain overlooked in the museum archive of Cornell University in New York, identified by Alexandra Kleinerman and Alhena Gadotti and published (Enkidu and the Harlot - Another fragment of Old Babylonian Gilgame) by Andrew George in 2018.

At first, the fragment does not look like much:

But working on the text, George noticed something strange.

The fragment is from the scene where Shamhat seduces Enkidu and has sex with him for a week.

Before 2018, scholars believed that the scene existed in both an Old Babylonian and a Standard Babylonian version, which gave slightly different accounts of the same episode:

The two scenes are not identical, but the differences could be explained as a result of the editorial changes that led from the Old Babylonian to the Standard Babylonian version.

However, the new fragment challenges this interpretation. One side of the tablet overlaps with the Standard Babylonian version, the other with the Old Babylonian version.

In short, the two scenes cannot be different versions of the same episode:

According to George, both the Old Babylonian and the Standard Babylonian version ran thus:

Suddenly, Shamhat and Enkidu's marathon of love had been doubled, a discovery that The Times publicized under the racy headline 'Ancient Sex Saga Now Twice As Epic'.

But in fact, there is a deeper significance to this discovery.

The difference between

the episodes can now be understood, not as editorial changes, but as

psychological changes that Enkidu undergoes as he becomes

human. The episodes represent two stages of the same narrative arc,

giving us a surprising insight into what it meant to become human

in the ancient world.

Enkidu replies that he will indeed come to Uruk, but not to befriend Gilgamesh:

Shamhat is dismayed, urging Enkidu to forget his plan, and instead describes the pleasures of city life:

After they have sex for a second week, Shamhat invites Enkidu to Uruk again, but with a different emphasis.

This time she dwells not on the king's bullish strength, but on Uruk's civic life:

Shamhat tells Enkidu that he is to integrate himself in society and find his place within a wider social fabric.

Enkidu agrees:

It is clear that Enkidu has changed between the two scenes.

The first week of sex might have given him the intellect to converse with Shamhat, but he still thinks in animal terms:

After the second week, he

has become ready to accept a different vision of society. Social

life is not about raw strength and assertions of power, but also

about communal duties and responsibility.

In a nutshell, what we

see here is a Babylonian poet looking at society through Enkidu's

still-feral eyes. It is a not-fully-human perspective on city life,

which is seen as a place of power and pride rather than skill and

cooperation.

We learn two main things.

In her second invitation to Uruk, Shamhat says:

Gods are here depicted as the opposite of animals, they are omnipotent and immortal, whereas animals are oblivious and destined to die.

To be human is to be placed somewhere in the middle:

In short, the new fragment reveals a vision of humanity as a process of maturation that unfolds between the animal and the divine.

One is not simply born human:

|