|

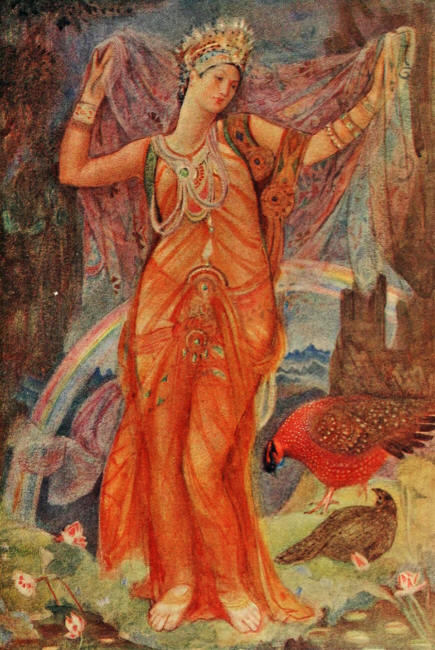

either Ishtar, the Mesopotamian goddess of love and war, or her older sister Ereshkigal, Queen of the underworld (c. 19th or 18th century BC)

BabelStone

It was not only so for everyday

humans but for kings and even deities.

Divine sex

Gods, being immortal and generally of superior status to humans, did not strictly need sexual intercourse for population maintenance, yet the practicalities of the matter seem to have done little to curb their enthusiasm.

Sexual relationships between Mesopotamian deities provided inspiration for a rich variety of narratives.

These include Sumerian myths such as Enlil and Ninlil and Enki and Ninhursag, where the complicated sexual interactions between deities was shown to involve trickery, deception and disguise.

The goddess Ishtar as depicted in

In both myths, a male deity adopts a disguise, and then attempts to gain sexual access to the female deity - or to avoid his lover's pursuit.

In the first, the goddess Ninlil follows her lover Enlil down into the Underworld, and barters sexual favors for information on Enlil's whereabouts.

The provision of a false identity in these myths is used to circumnavigate societal expectations of sex and fidelity.

Sexual betrayal could spell doom not only for errant lovers but for the whole of society. When the Queen of the Underworld, Ereshkigal, is abandoned by her lover, Nergal, she threatens to raise the dead unless he is returned to her, alluding to her right to sexual satiety.

The goddess Ishtar makes the same threat in the face of a romantic rejection from the king of Uruk in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

It is interesting to note that both Ishtar and Ereshkigal, who are sisters, use one of the most potent threats at their disposal to address matters of the heart.

The plots of these myths highlight the potential for deceit to create alienation between lovers during courtship.

The less-than-smooth course of love in these myths, and their complex use of literary imagery, have drawn scholarly comparisons with the works of Shakespeare.

Love poetry

Ancient authors of Sumerian love poetry, depicting the exploits of divine couples, show a wealth of practical knowledge on the stages of female sexual arousal.

It's thought by some scholars that this poetry may have historically had an educational purpose:

It's also been suggested the texts had religious purposes, or possibly magical potency.

Several texts write of the courtship of a divine couple, Inanna (the Semitic equivalent of Ishtar) and her lover, the shepherd deity Dumuzi.

The closeness of the lovers is shown through a sophisticated combination of poetry and sensuousness imagery...

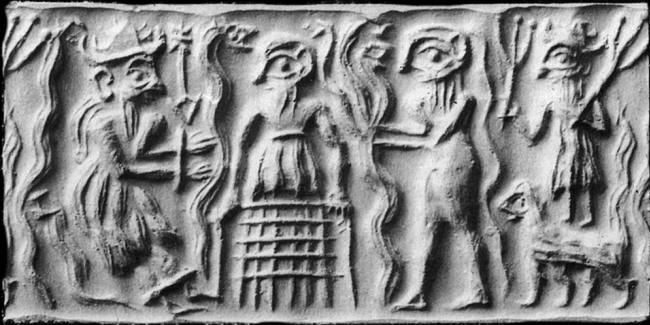

Ancient Sumerian cylinder seal impression

In one of the poems, elements of the female lover's arousal are catalogued, from the increased lubrication of her vulva, to the "trembling" of her climax.

The male partner is presented delighting in his partner's physical form, and speaking kindly to her. The feminine perspective on lovemaking is emphasized in the texts through the description of the goddess' erotic fantasies.

These fantasies are part of the preparations of the goddess for her union, and perhaps contribute to her sexual satisfaction.

Female and male genitals could be celebrated in poetry, the presence of dark pubic hair on the goddess' vulva is poetically described through the symbolism of a flock of ducks on a well-watered field or a narrow doorway framed in glossy black lapis-lazuli.

The representation of genitals may also have served a religious function:

Votive offerings in the shape of vulvae have been found in the city of Assur from before 1000 BC.

Happy goddess, happy kingdom

Divine sex was not the sole preserve of the gods, but could also involve the human king.

Few topics from Mesopotamia have captured the imagination as much as the concept of sacred marriage. In this tradition, the historical Mesopotamian king would be married to the goddess of love, Ishtar.

There is literary evidence for such marriages from very early Mesopotamia, before 2300 BC, and the concept persevered into much later periods.

The relationship between historical kings and Mesopotamian deities was considered crucial to the successful continuation of earthly and cosmic order.

For the Mesopotamian monarch, then, the sexual relationship with the goddess of love most likely involved a certain amount of pressure to perform.

In ancient Mesopotamia,

The general view now is that if there were a physical enactment to a sacred marriage ritual it would have been conducted on a symbolic level rather than a carnal one, with the king perhaps sharing his bed with a statue of the deity.

Agricultural imagery was often used to describe the union of goddess and king. Honey, for instance, is described as sweet like the goddess' mouth and vulva.

A love song from the city of Ur between 2100-2000 BC is dedicated to Shu-Sin, the king, and Ishtar:

Sex in this love poetry is depicted as a pleasurable activity that enhanced loving feelings of intimacy.

This sense of increased closeness was considered to bring joy to the heart of the goddess, resulting in good fortune and abundance for the entire community - perhaps demonstrating an early Mesopotamian version of the adage "happy wife, happy life".

The diverse presentation of divine sex creates something of a mystery around the causes for the cultural emphasis on cosmic copulation.

While the presentation of divine sex and marriage in ancient Mesopotamia likely served numerous purposes, some elements of the intimate relationships between gods shows some carry-over to mortal unions.

While dishonesty between lovers could lead to alienation, positive sexual interactions held countless benefits, including greater intimacy and lasting happiness.

|