|

Despite all efforts to convince us that these places were built by Tiwanakans, Incas and Nazcans, an air of mystery still surrounds the true identity of the original designers, who used technology equivalent to that of the twentieth century.

Most significantly, the experts cannot explain why such

huge, over-engineered monuments were built, often in the most remote

locations. Due to the experts’ lack of understanding, these

mysterious constructions are dismissed as “temples”.

The only difference is that the pyramids are conveniently labelled

as “tombs” rather than temples. We are thus told that the three

pyramids of Giza, as shown in Plate 28, were built by three pharaohs

from the third millennium BC - Khufu (whom the Greeks called Cheops),

Khafra (Chephren) and Menkaura (Mycerinus). In this chapter, I am

primarily concerned with the pyramid of Khufu. It is that pyramid

which is commonly referred to as the Great Pyramid and which

represents the last survivor of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient

World. But does the Great Pyramid really belong to the pharaoh named

Khufu, and was it ever a tomb?

There is a common perception that one

Egyptian pyramid is very much like another. Few people realize just

how special the Giza pyramids are, simply because no-one tells them.

One reference book dismisses the entire site as a vast necropolis,’

and it is difficult to find a book which does do full justice to all

of the incredible features of the Great Pyramid in particular. This

chapter will put the record straight, and in so doing it will become

transparently obvious that it was not built as a tomb by the ancient

Egyptians.

As one writer on Egypt, John Anthony West, put it:

According to the accepted chronology, Egyptian civilization emerged independently from any other civilization. It happened c. 3100 BC under the first pharaoh named Menes, who united, or possibly reunited, Upper and Lower Egypt (southern and northern respectively).

Who was Menes?

The experts can tell us nothing about him. What was the background to the battles he fought to unite Egypt? They cannot tell us. And why did the culture of ancient Egypt have so much in common with the Sumerian civilization which preceded it by 700 years? They deny it! And yet it is completely naive to assume that the Sumerians, who were keen travellers and explorers, did not influence Egyptian culture.

Whilst Egyptian tour-guides and experts attempt to dazzle us with their expertise on ancient Egypt, the truth is that they know very little. They use a chronology which has largely been constructed from Manetho’s Kings Lists, which were written long after the events occurred, and relied on fragmentary records which were thousands of years old.

Modern archaeology has provided precious little in the way of corroborative evidence to confirm the identities and dates of these kings. Therefore, the whole of Egyptian chronology is based on few facts and a whole lot of guesswork. However, it is not in the interests of the Egyptologists to admit to so many uncertainties! It is rather intriguing that Manetho’s Kings Lists recorded a long list of rulers prior to Menes.

According to Manetho, the reign of Menes was preceded by a 350-year period of chaos (at last some background!) and, prior to that, a dynasty of thirty demi-Gods had reigned for 3,650 years. That takes us back to around 7100 BC, well before any civilization had begun. But the fun has only just started, because Manetho also listed two further dynasties of Gods ruling for 13,870 years prior to that!

This valuable clue to mankind’s history is ignored, simply because the mention of Gods does not fit the historical paradigm of the experts. And yet this vast array of Gods is the central focus of ancient Egyptian art and religion. Some of the Egyptians God-legends are central to an understanding of their ancient cultural practices, but they are all studied under the banner of mythology.’

Nor was Manetho alone in recognizing these Gods as historical figures. Greek and Roman historians, such as Herodotus and Diodor of Sicily, also gave detailed accounts of divine kingdoms dating back thousands of years before the pharaohs. All of these ancient historians are mocked by modern historians for being so naive as to believe what the Egyptian priests told them.

Having hopefully established at least some doubt regarding the

reliability of Egyptian history, it is now time to take a closer

look at the Giza pyramids, particularly the Great Pyramid, and to

ask ourselves whether they really belonged to Khufu, Khafra and

Menkaura.

From the capital of Cairo, only a few miles away. the peaks of the two larger pyramids can be seen on the horizon to the north-west, above the sprawling city. From a distance, it is difficult to appreciate the huge size of these two pyramids. Only as one approaches, does the overwhelming scale of the construction become apparent.

The Great Pyramid itself, missing its capstone, was designed with a height of 480 feet, reaching the same height as Khafra’s pyramid but from a slightly lower base. This base covers an almost unbelievable area of 13 acres, with each side measuring 756 feet. The exterior of the Great Pyramid now appears very roughshod and badly eroded, but it was once covered in an outer layer of fine white limestone casing blocks, giving it the totally smooth sides of a true pyramid.

These casing stones were intact when Herodotus

visited the site in the fifth century BC, but most were later

removed for the construction of mosques in Cairo. Today, only a few

remain in museums and at the top of Khafra’s pyramid. These

six-sided stones, weighing up to 15 tons each, were polished and

precision carved to fit perfectly with each other and the core

stones, with joints measuring less than one fiftieth of an inch !

The Great Pyramid is often

cited as the largest building on Earth, with twice the volume and

thirty times the mass of New York’s famous Empire State Building.

The Pyramid rests on an artificially levelled platform, which is

less than 22 inches thick, yet is still almost perfectly level, with

errors of less than an inch across its entire area, despite

supporting such an enormous weight for thousands of years.6 The base

of the Pyramid is set out perfectly square - no mean feat of

engineering in itself.

Needless to say, scholars

have tried desperately hard to suggest how the ancient Egyptians

might have moved and erected stones of this size, but without

finding a convincing answer. As we noted in chapter 3, modern crane

technology would cope with these weights, but no-one is seriously

suggesting that the pharaohs could have designed and built such

state-of-the-art machinery. Furthermore, it is difficult to imagine

that even twentieth century technology would, in practice, be able

to match the Great Pyramid’s incredible precision.

The accuracy of the Great

Pyramid’s orientation is evidenced by the fact that Napoleon’s

engineers used it to triangulate and map northern Egypt.’

Furthermore, the Great Pyramid is placed almost exactly on the 30th

parallel north, a fact which will later prove highly significant.

One writer has described it as “bizarre and obviously alien in design”, an outrageous statement, but one for which any intelligent visitor could be reasonably excused.

A swivelling stone doorway to the Pyramid is so cunningly disguised that it was never discovered from the outside, and the visitor today uses the artificial entrance to the Pyramid through its north face, where the Moslem Caliph Al Mamoon forced an entry in AD 820.

This entrance leads directly to the Descending Passage and the Ascending Passage, each having an identical 26 degree angle to the horizontal.

When Mamoon forced his entry, he burrowed through the stone into the

Descending Passage, which led to a mysterious Subterranean Chamber,

hewn out of the bedrock directly below the apex of the Pyramid

(Plate 33). By chance, Mamoon’s men dislodged a stone from the

ceiling of the passage, revealing a large rectangular granite slab,

facing down at an unusual angle. They

tunnelled around what later became known as the Granite Plug, and

became the first men to discover the Ascending Passage, which led to

the upper chambers of the Pyramid.

This niche is technically described as a corbelled telescopic cavity, but neither this term, nor niche, do justice to the extraordinary shape and size of this feature which stands just over 15 feet high (Plate 30). Whatever it might have contained is unknown, for the Queen’s Chamber was found totally empty. Needless to say, this remarkable niche is another totally unique feature in Egyptian pyramids.

The Grand Gallery continues to ascend at an angle of 26 degrees, for a distance of 153 feet, and with a height of 26 feet. It is difficult to find words to describe its intricate and precise design. It is best described as a corbelled telescopic vault, which is similar in pattern to the Queen’s Chamber niche, but on a grander scale, and with seven corbelled overlaps rather than five. Each corbel overlaps the lower one by three inches, so that the Gallery narrows as it rises.

Just

above the third corbel, a curious and inexplicable groove runs the

whole length of the Gallery, whilst on its floor, two ramps, one on

each side, contain mysterious niches (Plate 32). The groove and the

niches are rarely mentioned by the experts, since their symbolism is

impossible to determine, and they could not, according to these

experts, have had any practical purpose. Whatever they might have

contained is unknown, but damage to the Gallery’s walls, alongside

each niche, strongly suggests that something was forcibly removed in

ancient times.

Three other granite slabs, for

which vertical grooves have been cut, are presumed missing. When

lowered, these slabs would originally have descended to 3 inches

beneath floor level. The uppermost part of the Antechamber contains

unusual semi-circular hollows on one side, leading even the cautious

experts to acknowledge some form of sophisticated portcullis device,

which could lower the hard granite slabs to block access to the

King’s Chamber.

This is a complete fabrication, and one

despairs at such irresponsibility from an authoritative text book

which many readers will accept without question. Both the King’s

Chamber and the Queen’s Chamber each contain a pair of so called

airshafts small rectangular shafts with a cross-section measuring

approximately 8 inches by 8 inches. This is yet another unique

feature, seen in no other pyramid in Egypt. Whilst the airshafts in

the King’s Chamber extend to the Pyramid’s outer layer of masonry,

those in the Queen’s Chamber do not, thus disproving the myth that

they really could have functioned as airshafts.

Suffice to say, for

now, that the small doorway with metal handles, discovered by

Rudolf Gantenbrink in one of the Queen’s Chamber airshafts, suggests that

it played a functional rather than a symbolic purpose.

Why is 52 degrees so important? This angle embodies in the Pyramid the mathematical pi factor,!’ but more significantly, it is only at 52 degrees that the ratio of the height of the Pyramid to its base perimeter is exactly the same as that of the radius of a circle to its circumference! Furthermore, the 52-degree pyramid also builds in the special geometric feature of the golden section.

The technical difficulties with building at the extremely steep angle of 52 degrees are evidenced by the collapsed pyramid at Maidum and the Bent Pyramid at Dahshur. the latter having been changed in mid-construction to the safer angle of 43.5 degrees (Plate 29). This angle also embodies pi, but not in the perfect sense of the 52-degree pyramid.

The mathematical symmetry of the Great Pyramid is such that the angles of the Ascending and Descending Passages, when added together, closely approximate the 52-degree angle at which the Pyramid itself rises from the ground. All studies of the pyramids have confirmed the use of pi in their design, and caused a reassessment of the mathematical knowledge of the Egyptians.

Unfortunately, the more measurements that are taken, the more likely that arbitrary or coincidental relationships will turn up, and this has certainly happened in the case of the Great Pyramid, where many researchers have been determined to find new relationships to fit their preconceived theories. Nevertheless, the more outrageous and contrived claims should not be allowed to detract from the many genuine features of the Pyramid which are truly astounding.

We have already covered its polar alignment and

aspects of the amazing scale and features of the design; it is now

time to get down to the nitty gritty.

As if this was not incredible enough, all of these stones were found to be joined together with an extremely fine but strong cement, which had been applied evenly on semi-vertical faces across a surface expanse covering 21 acres on the Great pyramid alone!

Sir William Flinders Petrie, one of the most eminent archaeologists to have studied Giza, commented:

The second example is the internal passages of the Great Pyramid.

These passages have been measured countless times and found to be perfectly straight, with a deviation, in the case of the Descending Passage, of less than one fiftieth of an inch along its masonry part. Over a length of 150 feet that is incredible. If one includes the further 200 feet of passage bored through the solid rock, the error is less than one quarter of an inch. Now this is engineering of the highest precision, comparable with twentieth century technology, but supposedly achieved 4,500 years ago.

Our third example is the machining of granite within the pyramids. One of the first archaeologists to carry out a thorough survey of the Pyramid was Petrie, who was particularly struck by the granite coffer in the King’s Chamber. The precision with which the coffer had been carved out of a single block of extremely hard granite struck him as quite remarkable.

Petrie estimated that diamond-tipped drills would need to have been applied with a pressure of two tons, in order to hollow out the granite box. It was not a serious suggestion as to the method actually used. but simply his way of expressing the impossibility of creating that artifact using nineteenth century technology. It is still a difficult challenge, even with twentieth century technology.

And yet we are supposed to believe that Khufu achieved this at a time when the Egyptians possessed only the most basic copper hand tools. In 1995. an English engineer named Chris Dunn visited Egypt with the express intention of figuring out how their granite artifacts were produced.

Dunn appeared to me to have the right qualifications for the task, including an open mind, for in his own words used, but simply his way of expressing,

Dunn visited the Cairo Museum, the pyramids and the granite quarry at Aswan, in an attempt to figure out the processes that were used.

It quickly became clear to him that many of the artifacts could not have been made without the use of very advanced machinery:

Chris Dunn found that many artifacts bore the same marks as conventional twentieth century machining methods sawing, lathe and milling practices He was particularly interested, however, in the evidence of a modern processing technique known as trepanning.

This process is used to excavate a hollow in a block of hard stone by first drilling, and then breaking out, the remaining “core” Petrie had studied both the hollows and the cores, and been astonished to find spiral grooves on the core which indicated a drill feed rate of 0.100 inch per revolution of the drill. This initially seemed to be impossible.

In 1983, Dunn had ascertained that industrial diamond

drills could cut granite with a drill rotation speed of 900

revolutions per minute and a feed rate of 0.0002 inch per

revolution. What these technicalities actually mean is that the

ancient Egyptians were cutting their granite with a feed rate 500

times greater than 1983 technology!

Dunn posed the same challenge independently to another engineer, and eventually they both came to the same conclusion - the only possible method which fitted all the facts was ultrasonic machining! In the late twentieth century, the ultrasonic tool-bit has found particular favour in the precision machining of unusually shaped holes in hard, brittle materials such as hardened steels, carbides, ceramics and semiconductors.

Chris

Dunn compares the drilling process to the motion of a jackhammer on a

concrete pavement, but vibrating faster than the eye can see, at

19,000-25,000 cycles per second. Assisted by an abrasive slurry or

paste, the tool bit cuts by an oscillatory grinding action. This

feature, and only this feature, can explain the groove cut deeper

into the harder quartz.

The unavoidable conclusion is that whoever

built the Giza pyramids possessed extraordinary machinery and the

capability to use it. Furthermore, the accuracy is such that the

cutting tool alone is not sufficient. These tools must have been

guided, not by the human eye, but by computer.

The show, entitled Mysteries of the Pyramids Live was hosted by Omar Sharif, interviewing a supposedly expert Egyptologist. In front of millions of viewers, the expert stated “we know that the pyramids were built by the ancient Egyptians 5,000 years ago”.

That sweeping statement was followed by the alleged proof - a royal cartouche of Khufu’s name, painted inside the Great Pyramid.

Upon hearing the expert’s explanation of the cartouche, Sharif gratefully exclaimed:

As we shall soon see, the American public were provided with total dis-information by Mysteries of the Pyramids Live.

But before dealing with the alleged proof by cartouche, let us

examine the other evidence often cited in support of Khufu’s

pyramid. In the fifth century BC, the Greek historian Herodotus

returned from a visit to Egypt, claiming that the three pyramids at

Giza belonged to Khufu, Khafra and Menkaura. Herodotus may have been

a great historian, but evidently he relied on the word of his hosts

- the Egyptian priests. How do we know that they told him the truth?

He therefore left the most interesting questions unanswered.

Other than

the word of Herodotus, there is only one single piece of evidence

that the Great Pyramid may have belonged to Khufu - a painted

cartouche of Khufu’s hieroglyphic name, found inside the Pyramid by

an English archaeologist, Colonel Howard Vyse.

Driven by frustration and ambition, Vyse then proceeded to have a cartouche of Khufu’s name forged a most unlikely place - an enclosed space between the giant granite slabs above the King’s Chamber of the Great Pyramid.

How do we know this? Due to a long-overdue and thorough investigation in 1980 by Zecharia Sitchin. I will now summarize the overwhelming evidence cited by Sitchin.

How can we be so sure of a fraud by Vyse? The most damning evidence against him is a series of errors in the various markings and cartouches which were found daubed in red paint. Incredible as it may seem, the first suspicions of a fraud were raised in 1837, shortly after the discovery was made.

Vyse had sent copies of the cartouches to the British Museum for confirmation. It has always been assumed that the opinion of its hieroglyphics expert Samuel Birch, supported the reading of the cartouche as Khufu.

This was not the case, and in fact Birch expressed many doubts. In particular, he noted that many of the marks were curiously indistinct and that some of the symbols were highly unusual, never found in Egypt before (or since). He was also puzzled by the style of the script which did not begin to appear in Egypt until centuries later; some of the symbols could only be matched closely to ones appearing 2,000 years after time of Khufu.

Birch even found a symbol for an adjective used as a numeral - a basic grammatical error. It is also little known that Birch found the names of two pharaohs in the inscriptions, a fact which he was totally unable to explain. He concluded that “the presence of this (second) name, as a quarry mark, in the Great Pyramid, is an additional embarrassment” (emphasis added).

This did

indeed embarrass the Egyptologists, for it fundamentally called into

question the authenticity of the inscription and their conclusion

that the Pyramid belonged to Khufu. The matter has conveniently been

left unresolved for over a hundred and fifty years!

One of these

books, Materia Hieroglyphica, by Sir John Gardner Wilkinson, a

standard reference work at the time, was constantly referred to in Vyse’s diaries. Unfortunately for Vyse, Wilkinson’s work was

subsequently shown to contain various errors. In particular, it

confused the sign for Kh with the sign for the solar disk

representing Ra. The royal name found inscribed in the Great Pyramid

contained exactly the same mistake.

Sitchin summarizes as follows:

This undeniable proof of the forgery explains a number of other strange occurrences during Vyse’s visit to Egypt:

It also explains why no

inscriptions were found in the first compartment above the King’s

Chamber, discovered by the earlier archaeologist Nathaniel Davison

in 1765, but only in those higher compartments opened by Vyse.

The full story revealed by Sitchin is highly incriminating of Vyse and his loyal assistant Mr Hill.

The motivation of Vyse to embark on such a fraud is not hard to fathom, given that he was running out of both time and money, finding nothing, and, by his own admission,

We are left with only two possibilities - either the markings were placed by an illiterate workman when the Great Pyramid was built, a workman who did not know for sure who his king was, or the whole episode was a shameful archaeological fraud.

Having proved Khufu’s (or should we say Ra-ufu’s!) cartouche to be a fraud, there is absolutely no other evidence, other than the word of Herodotus, to identify the Great Pyramid with Khufu.

The same applies to the other two pyramids, allegedly of Khafra and Menkaura. It is therefore hardly surprising that Zecharia Sitchin’s evidence has not been refuted, but rather ignored by the Egyptologists.

Who can blame

them for such a tactic, since if they were to admit the Pyramid does

not belong to Khufu, they would have to admit that they do not know

who it belongs to - an embarrassing admission for the so-called

experts.

The British Museum attributes the Great

Pyramid’s “unusual internal design” to “the result of alterations in

plan during construction” - a direct reference to the traditional

theory that each of the chambers was intended as a tomb, and that

therefore the builders must have changed their minds during the

course of construction.?’

To the surprise of many who have taken the tomb theory at face value. no body, no mummy. nothing at all connected in any remote way with a burial or a tomb, has ever been found inside the Great Pyramid. The Arab historians, who recorded Mamoon’s entry into the Pyramid, stated that there was no evidence of a tomb, and no evidence of grave robbers, since the upper par of the Pyramid had been very effectively sealed off and hidden.

No grave robber would have sealed a tomb after robbing it he would be more interested in a quick getaway! The unavoidable conclusion from this line of reasoning is that the Pyramid was designed to be empty. Furthermore, the idea that the upper chambers of the Great Pyramid were ever designed for a burial is quite inconsistent with the fact that not one Egyptian pharaoh ever had their tomb placed high above ground level. In fact, a study of the numerous other pyramids in Egypt reveals no evidence that any of them were ever used as tombs.

It was an extremely ambitious project, supposedly unique and without precedent in Egypt (although similar ziggurats were being built in Mesopotamia centuries earlier). He was assisted in this task by an architect named Imhotep, a shadowy character about whom little is known.

Djoser’s pyramid was built at an angle of approximately 43.5 degrees. In the early nineteenth century, two “burial chambers” were discovered underneath Djoser’s pyramid, and further excavations revealed underground galleries with two empty sarcophagae. It has since been generally accepted that this pyramid was a tomb for Djoser. and also for members of his family, but in fact his remains have never been found. and there is no hard evidence that Djoser was ever buried in the pyramid.

On the

contrary, many eminent Egyptologists are now convinced that Djoser

was buried in a magnificent, highly decorated tomb, discovered in

1928, to the south of the pyramid. They can only conclude that the

pyramid itself was never designed as a proper tomb, but represented

either a symbolic tomb or an elaborate scheme to fool grave-robbers.

Other lesser-known pyramids of the Third Dynasty follow a similar theme: the step-pyramid of Khaba was found completely bare; nearby was discovered another unfinished pyramid with a mysterious chamber, oval-shaped like a bath-tub, sealed and empty; and three other small pyramids contain no evidence of burials whatsoever.

The first ruler of the Fourth Dynasty, c. 2575 BC, was Sneferu. Here the pyramids-as-tombs theory takes another blow, for Sneferu is believed to have built not one but three pyramids!

His first pyramid. at Maidum, was built too steep and collapsed. Nothing at all was found ill the burial chamber other than fragments of a wooden coffin, believed to have been a later, intrusive burial. Sneferu’s second and third pyramids were built at Dahshur.

His second, known as the Bent Pyramid (Plate 29), is believed to have been built at the same time as that at Maidum, for the angle was suddenly changed in mid-construction from around 52 degrees to the safer angle of 43.5 degrees. The third pyramid is known as the Red Pyramid. after the local pink limestone which had been used, and this one rose at a steady but safe angle of around 43 degrees.

These pyramids had two and three “burial chambers” respectively, each of which was found to be totally empty. Why did Sneferu require two pyramids close together, and what was the symbolism of the Empty chambers. Having gone to such an effort, why would he be buried elsewhere? Surely one false tomb is enough to fool the robbers!

Now Khufu is believed to

be the son of Sneferu, so we arrive at the supposed construction

date of the Great Pyramid at Giza without one shred of evidence that

the pyramid was ever intended to be a tomb. And yet all the books,

all the tour guides and all the television documentaries start

categorically and repeatedly that the pyramids at Giza, like all the

other pyramids in Egypt, were tombs!

Should we continue to blindly

believe what these experts are telling us?

If we ignore this circular argument and examine the facts outlined so far, then the whole question of the builders and dates of construction of the Giza pyramids is wide open. The only clue we do have is that twentieth century technology was used in their construction.

The official chronology starts with the 43.5-degree step-pyramid of Djoser, followed by pyramids such as those of Sekhemkhet and Sneferu. Within one hundred years of Djoser we are expected to believe that a huge leap in technology enabled Khufu and his successors to build, with incredible precision, the 52-degree pyramids at Giza. Not only did they build pyramids in a different league to those which had gone before, but they also added unique design features which had never been seen before.

The whole of the upper system of passages and chambers in the Great Pyramid is absolutely unique at this point the Egyptologists conveniently pass by Khufus son Radjedef who, for unexplained reasons, chose not to use Giza, but selected a site some miles to the north.

Khafra and

Menkaura then returned to Giza to build their pyramids.

There then followed the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties of pharaohs, who did build some fine pyramids (once again featuring empty “burial chambers”) such as that of Sahure, but never again on a par with Giza. The Sixth Dynasty saw a change in style with the pyramids of Unas, Teti. Pepy I, Merenre and Pepy II, which were elaborately decorated with the famous Pyramid Texts, but still included empty sarcophagi.

I would now like to put forward a much more plausible theory - that the Giza pyramids preceded all of the other pyramids in Egypt and that they acted as a model for them. I would like to suggest that someone was once privy to the knowledge of the empty coffer which was hidden in the sealed upper section of the Great Pyramid.

The later pharaohs then copied the empty boxes, which they believed to be symbolically important.

Is there any evidence for the Giza-First theory? Recent findings

from an American archaeological mission have shown that Djoser’s

pyramid at Saqqara was originally cased with primitive mud bricks

whitewashed to simulate white limestone, which soon crumbled to

leave the impression of a step-pyramid. Djoser’s original pyramid

would therefore have resembled those at Giza, with their gleaming

white limestone casing stones.

The theory is further strengthened by the fact that the angle of the Bent pyramid at Dahshur was altered in mid-construction, suggesting that it was being built simultaneously to that at Maidum. It is therefore significant that, when the Maidum pyramid collapsed, Sneferu continued his ambitious two-pyramid scheme by constructing the Red Pyramid nearby. Protrusions on the side of the Red Pyramid indicate that it too may have been designed to support a white limestone casing, in emulation of Giza.

If the Great Pyramid already existed,

then we cannot attribute any known pyramid to Sneferu’s son, Khufu.

It has been suggested that, in view of the difficulties in

replicating the 52-degree angle, Khufu may have decided to forego

the hassle of building his own pyramid; instead he chose to adopt

the Great Pyramid as his own by building a temple nearby, whilst

hiding his tomb somewhere in the vicinity.

The apparent decline in technology after Khufu, Khafra and Menkaura, which has mystified the Egyptologists now becomes understandable, since there was never a peak in technology at all, only a decline from the true 52-degree originals of Giza.

When the pyramids on the Giza site had been fully adopted by the pharaohs, later pharaohs resorted to building their own pyramids. The final test is, of course, to prove the age of the Great Pyramid to be older than 2550 BC. We will return to this question in a later chapter. For now I will mention as evidence only the well known victory tablet of the very first pharaoh Menes (also known by the name Nar-Mer).

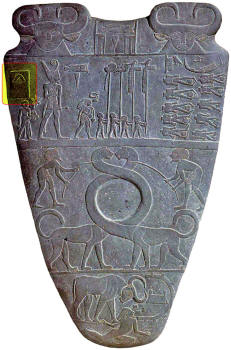

This tablet, exhibited in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, depicts the forceful unification of Upper and Lower Egypt by Menes c. 3100 BC. The tablet has been comprehensively studied by scholars, who are agreed that its symbols accurately represent the various places and enemies encountered during Menes’ campaign.

But, as Zecharia Sitchin has pointed out, one symbol has been conveniently ignored.

Plate 34

It is a pyramid-shaped symbol in the top left section of the tablet (Plate 34) which represents Lower Egypt - an accurate location for the Great Pyramid!

This is only one piece of evidence, which does not constitute a proof, but it does seem to suggest that the Giza pyramids already existed in Egypt c. 3100 BC.

Finally, how do we explain the fact that Herodotus attributed the Great Pyramid to Khufu? If the pyramids already existed before civilization began in Egypt, the Egyptian priests may simply not have known who built the pyramids, but knew they had been “adopted” by Khufu and his successors. Could it be that an overeager Herodotus, thirsting for knowledge as historians do, fell into the trap of pushing the priests so hard that they told him lies to shut him up?

Human nature does not change, even over two thousand years. We should remember that Herodotus never answered the really interesting question of how the pyramids were built.

It would have been quite easy for the

priests to furnish Herodotus with an answers to the question of

“who”, but much more difficult to explain the “how” and the “why”,

if they did not know.

In England, Stonehenge was built at a time before any society was supposed to exist. In South America, Tiwanaku was built thousands of years before history officially began. In Lebanon, the platform at Baalbek has never been dated, but legends place it, too, in a time before recorded history.

The pyramids of Giza belong in the same category - before records began in Egypt. All of these sites have one other thing in common. They carry no inscriptions of any kind commemorating their builders. It is as if - all around the world - there is a shadowy prehistory that precedes the official history of civilized man.

Out of this history, a legacy has passed down to only now be recognized in the twentieth century. It is not surprising that many people have therefore been drawn to the idea of Atlantis. But what kind of people were these Atlanteans who never left their names or those of their Gods?

It is no coincidence that our open-minded study of the Great Pyramid has catapulted it back in time, before Menes, to the dynasties of the Gods which were recorded by Manetho.

But it leaves us asking many questions.

The ancient Egyptians texts record legends of flesh-and-blood Gods.

One legend describes the “winged disc” of Ra, which was flown into battle by Horus. There is also reference to a foundry of “divine iron” at Edfu and an underground complex known as the Duat, from which the pharaohs could soar heavenward. Are these tales the product of superstitious imagination, or memories of actual events and reallocations?

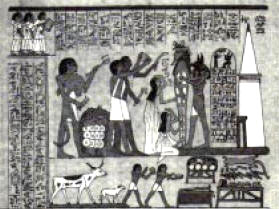

The Ani Papyrus, housed in the British Museum, depicts the pharaoh’s trip to the afterlife. The climax of the journey involves the “opening of the mouth” ceremony, which I hinted in might refer to the “mouth” of an underground chamber.

At this ceremony, the Ani Papyrus shows the mummified body of the pharaoh accompanied by what appears to be a rocket (Figure 3).

Our preconceptions are so deeply ingrained that we want to laugh aloud at the notion, but how can we dismiss the incredible technology that exists within the pyramids at Giza - “space age technology” in the words of the English engineer Chris Dunn?

This state-of-the art

precision technology is not inconsistent with the ability to build

rockets or aircraft. When we consider also the evidence from Nazca

and Baalbek, some of the wilder theories of the pyramids as beacons

for aerial navigation now do not sound so fanciful.

What if the

Egyptians knew that the pyramids at Giza played a role in the

navigation to the Duat, there flesh-and-blood Gods, perceived to be

immortal, ascended to the heavens? A religion could thus form (like

the Cargo Cult) which required the building of a pyramid (or two) to

emulate Giza, and an empty granite box to replicate the one in the

King’s Chamber.

But why four shafts?

Our mysterious pharaoh must have been quite a cosmic traveller! And why would Sneferu build himself three pyramids? What is the point of three eternal lives when you have one!

All of the establishment theories have their roots in Egyptian mythology, but at the same time they deny any reality within that mythology. And, in that denial, they lose credibility in explaining why such powerful religious beliefs came about. Thus we are expected to believe that the Egyptians’ fear of death was so great that they invented a means to an afterlife.

This is all very well, but would

it really have inspired them to pile millions of limestone blocks

one on top of the other? And where would the unique idea of a

pyramid-shape have come from, for what possible connection is there,

in an abstract sense, between a pyramid and everlasting life!

I will also establish the pyramids’ date of

construction and explain the motivation of the Gods who built them.

Finally, I will put forward a theory that explains all of the Great

Pyramid’s features based on functional rather than a symbolic

interpretation.

Back to La Gran Piramide y Sus Secretos

|