|

by Marko Kovic December 04, 2018 from AEON Website

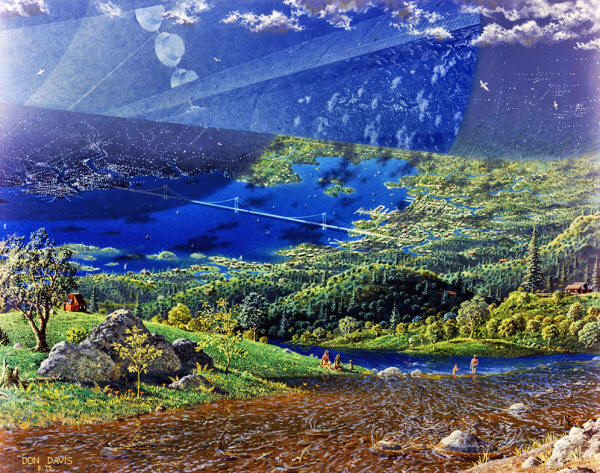

Artist's impression of a cylinder colony, endcap view with suspension bridge. Art by Don Davis, 1970s. Image courtesy NASA Ames Research Center

a legal framework for space colonization the consequences could be catastrophic:

the time to act

is now...

The year is 2087...

Thanks to a series of serendipitous technological breakthroughs a few decades earlier, the creation of large-scale, self-sustainable human habitats beyond Earth has become feasible.

There are already close

to half a million people living on Mars, many of them native

Martians.

They are, in effect,

foreign territories of the US and of China where people live and

work essentially the same way as they do on Earth.

Unsurprisingly, neither the US nor the Chinese governments have recognized the referendum.

Whereas the US government

is still deliberating on an appropriate course of action, China has

already sent its warships to Mars to suppress the 'insurgency' with

any means necessary, including an armed invasion both of the

Chinese- and the US-controlled habitat.

The answer is no. There is no meaningful space-colonization governance framework to speak of.

As of now, in 2018, space

colonization is a veritable free-for-all. And this absence of a

forward-looking space-colonization governance framework could have

disastrous consequences.

Building a private house for yourself is relatively simpler in terms of governance rules than building a large commercial high-rise, and building a high-rise is relatively simpler than building a transcontinental bridge, and so forth...

Even though people tend to dislike the labyrinthine ways of bureaucratic procedure and the frustrating reality of red tape, governance is both necessary and a blessing.

Rules that govern human activity reduce transaction costs, create planning security, and increase the probability of good outcomes in uncertain decision-making contexts. The epistemic and moral progress of human civilization seems to, at the very least, correlate with progress in collective governance.

We live in a

rules-based world, and we are better off for it.

That is why space-colonization governance should be a global priority even today, before colonization is technologically viable.

If we fail to create an adequate governance framework for space colonization, we risk,

There is an almost infinite amount of specific possible governance scenarios in which some kind of space colonization activity might cause some kind of problem.

Speculating about specific scenarios and spectacular ways in which things might go wrong is, therefore, somewhat of a never-ending story.

From a conceptual, birds-eye view, however, possible space-colonization governance problems fall into one of four general categories.

These four challenges will be the direct consequences of four major colonization milestones on a timeline that begins today (no colonization) and ends with humans inhabiting one or several large-scale independent and sovereign habitats (an independent planet Mars, for example).

In theory, the first question, regarding who is allowed to engage in space colonization, is addressed in the Outer Space Treaty from 1967, which is the current foundation of extraterrestrial governance, and a remarkable historical milestone.

Crafted by the US and the

USSR in the wake of nearly disastrous confrontations, it stipulates

that space and natural celestial bodies cannot be appropriated or

claimed by governments and, more generally, space can be explored

and used only for peaceful purposes.

It does not really solve the problem of who is allowed to engage in space colonization.

For example, under the Outer Space Treaty, private actors such as SpaceX are allowed to engage in colonization activity, but it is not clear whether all kinds of commercial activities are permissible:

Furthermore, even though the Outer Space Treaty's clause against occupation sounds sensible, it is not clear what it means in practice.

If NASA were to install a habitat on Mars,

The second challenge, the problem of governance within early colonies, is also touched upon by the Outer Space Treaty.

The jurisdiction of any spacecraft and any personnel on that spacecraft, the treaty stipulates, is the jurisdiction of the spacecraft's and/or the personnel's country of origin.

The principle is simple, and it has proven workable for complex international missions such as the International Space Station.

However, governance within early colonies will not be able to rely on this principle alone, for two reasons.

The first is distance:

The second reason,

In the context of low Earth orbit missions, conflict resolution can work through direct commands or through aborting missions, but in distant habitats, the colonists will need to have means of local conflict resolution.

Colonies are not just missions - they are communities.

For these communities to thrive, they will need well-thought-out rules of governance, and the country-of-origin-principle is too simplistic to be useful.

There is no good reason to think that any future space colony could actually be

a direct

'democracy'...

Elon Musk, the founder and CEO of SpaceX, has proposed direct democracy as the governance system for a future Mars colony in which all colonists directly exert law-making power instead of appointing representatives in legislative bodies.

True direct democracy means:

That sounds great in

principle, but there are major problems with direct democracy.

Also, the practical realities of true direct democracy are very challenging.

As the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau remarked in 1762, true direct democracy is suitable to gods, not to us fallible humans, because direct democracy requires an impossible amount of resources:

There is

no true direct democracy in the world today

so there is no good reason to think that any future space colony of

nontrivial size could actually be a direct democracy.

An authoritarian approach might seem appealing given that the reputation of democracy as a problem-solving framework has suffered in recent times (as well as the enormous economic and technological progress that China has experienced in a recent decades).

To be sure, some aspects of early colonization efforts will automatically default into something like autocratic decision making since spacecraft passengers en route to their destinations will have to submit to the orders of the crew (much as civilian passengers on airplanes do today).

But authoritarianism is unlikely to be a viable governance framework in early colonies.

Endowing a single

colonist or a group of colonists with immutable decision-making

powers is dubious at best. The potential benefit of a benevolent and

competent dictatorship is outweighed by the risks of an abusive and

incompetent dictatorship. Authoritarianism is a bad bet in the long

run.

If we model intracolonial governance as authoritarian regimes, we risk making bad and incorrigible mistakes. Governance within early colonies should, ideally, find a middle ground between sound democratic decision making and technocratic expertise and analysis.

Finding that middle

ground will be challenging, as will figuring out how and when very

early exploration missions should transition into more complex and

more autonomous modes of governance.

Even if we manage to muddle through the early colonization efforts with imperfect governance schemes, governance will be even more critical once colonies become larger and more self-sustaining.

The idea of secession and independence will take root sooner or later in the colonies, as it arguably should: if the whole point of space colonization is for humankind to safely exist beyond Earth, then large and mature colonies should not be controlled by Earth indefinitely.

The goal is for humankind

to spread beyond Earth, not for Earthlings to send obedient servants

into space.

However, it is not clear

how independent habitats are supposed to come about.

The colony is fully self-sufficient and sustainable and, in a referendum, the Venusians opt for secession from Earth.

Secession is immensely

challenging even within the context of advanced Western democracy.

Though sovereignty and self-determination have become a generally

recognized principle with

the United Nations' Declaration on

the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples

in 1960, the reality has always been

complicated.

We need to define the prerequisites for secession:

We need to define the target political system of aspiring independent habitats:

Finally, we need to

define the actual process of seceding so that the transition from

colony to independent habitat is as smooth and peaceful as possible.

we risk the horrors of past independence movements

on an immense

new scale...

It is hard to imagine that the US, a 'democratic' country, and China, an 'authoritarian' regime, will readily agree on a secession protocol for future space colonies:

And herein lies the problem:

Let us be optimistic and imagine that the first three major governance challenges have been overcome in the best of all possible ways.

We now have two independent and sovereign human habitats, Earth and Venus, existing on equal footing with one another.

In such a setting, the fourth and quite possibly biggest governance challenge of space colonization arises:

The benefits of pan-human governance in the age of space colonization are the same as the benefits of global governance today:

In the case of space colonization, pan-human governance would also have the additional benefit of counterbalancing the centrifugal effect that large distances are likely to create in terms of cultural and moral trajectories within different habitats.

A colonized future in

which there is no pan-human governance and in which disparate

habitats go their own ways does not seem desirable, not least

because such a development could increase the risk of total

separation of different strands of humankind, with the accompanying

risk of eventual conflict (Space

Colonization and Suffering Risks - Reassessing the "Maxipok Rule").

A good approach might be to continue using the system that we currently have, and try to expand it in order to incorporate the new layer of extra-terrestrial expansion.

That would mean our current common polity and governance levels of the local, regional, national and international levels would be expanded to include something like an interplanetary or inter-habitational level.

Introducing new layers of governance usually means that the sovereignty of actors on lower governance levels is being eroded, and it will almost certainly prove challenging to reconcile the smallest level of sovereignty, individual freedoms and decision-making capabilities with the new highest-order level of sovereignty, a Federation of human habitats.

However, if historic data offer a clue as to what might happen, it could very well be that the creation and expansion of higher-order levels of sovereignty does not necessarily do away with lower-order sovereignty. Indeed, the adoption of higher-order levels of sovereignty could result in a net gain in some forms of sovereignty on lower-order levels.

An example (State

Sovereignty and International Human Rights) for this

counterintuitive effect was the codification and (at least formal)

proliferation of

the idea of human rights.

While we are, of course,

still far from having detailed solutions to each challenge, we can

and should start thinking about general strategies for how we might

arrive at a specific solution. To my mind, there are three such

strategies.

We can decide to do nothing in particular and let history take its course, with the expectation that we will successfully cross the bridge in question when we get there.

After all, it has worked out in the past. This position is understandable, and is probably rather prevalent.

For example, Steven Pinker, a tireless advocate for science and reason, seems to reject the notion of existentially catastrophic outcomes because the history of human civilization has so far been a history of progress, not of catastrophe. But the 'waiting for the bridge' approach is dangerous.

Even though the history of humankind is, overall, a history of things getting better, it doesn't mean that things simply get uniformly better.

Global governance, in fact, is a sad example of that:

And then there is the so-called survivorship bias...

Yes, we have done OK so

far, but that fact is not a guarantee that things will continue to

be OK. Maybe we were just lucky. Judging, for example, by the

numerous nuclear close-calls during the Cold War, we might not want

to put too much faith into our ability to muddle through.

We could estimate the general chronological order of governance challenges, and try to find solutions in that order. In contrast to the 'waiting for the bridge' strategy, we would be trying to do so in advance, before we reach the proverbial bridge.

This kind of strategy is preferable not least because it represents a form of planning instead of letting things happen.

If the international

scientific and policymaking communities were to adopt

incrementalism, there is the

possibility that we would not only be setting the stage for each of

the colonization milestones to come, but we would be creating

positive incentives for colonization - after all, good governance

rules can incentivize good and desired behavior.

Creating an organization that has the political authority and legitimacy to act as a pan-human Federation would mean creating a body that is tasked with finding solutions for the taxonomically lower problems of a Federation for space-colonization governance.

The Federation would, in

other words, reverse-engineer governance solutions for the

challenges that lie behind it. It would have to bootstrap successful

space-colonization governance into existence.

If the pan-human Federation is based on a reasonable enough charter and has a reasonable approach to its procedures, the decisions of a one-member pan-human Federation will not be detrimental to future habitats beyond Earth.

Quite the opposite:

By creating this proto-pan-human Federation, we would automatically acknowledge the right of future colonies to pursue self-determination and independence.

The specifics of colony

secession and independence would still have to be worked out, but it

would be made easier by agreeing first on the overall long-term goal

of space colonization.

Bringing this new layer of political reality into existence requires leadership from one or several powerful countries.

A push for a pan-human Federation led by 'the US' (and partner countries) would probably attract other countries as well, both because the benefits of cooperation are obvious and because every country has a strategic desire not to be left behind in matters of space-colonization governance.

The act of creating a pan-human Federation could be 'channeled' through the United Nations...

Flawed though it might be, the UN has a reasonable track record of bringing the countries of the world together in order to work on pan-human problems.

Of course, the pan-human

Federation cannot be a mere agency of the UN, but the UN could act

as the institutional midwife for bringing the pan-human Federation

into the world.

|