|

by Kristen Minogue

18 November 2010

from

ScienceMagazine Website

Improbable

world.

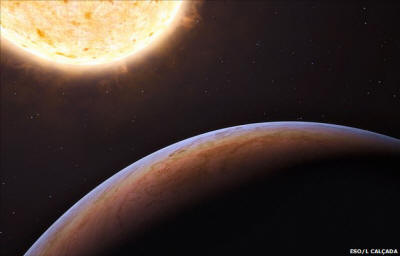

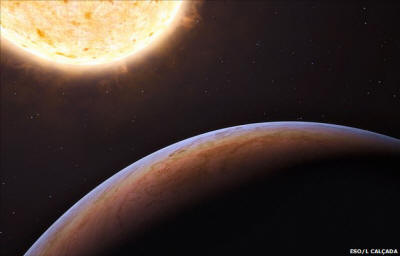

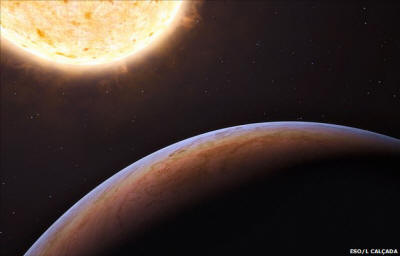

An artist's depiction

of a planet like the one discovered,

caught in the orbit

of an old, violent star.

Astronomers have detected what they

believe to be a planet at least the size of Jupiter that came from

another galaxy.

If true, the world is the first

planetary immigrant ever detected in the Milky Way. The find would

also violate the leading hypothesis of how and where planets form.

The planet lives 2200 light-years away inside the

Helmi stream, a

ring of ancient stars that cuts through the plane of the Milky Way.

Astronomers believe the stream formed 6 billion to 9 billion years

ago, when the Milky Way ripped another galaxy to shreds, swallowing

some of its stars in the process.

Astronomer Johny Setiawan of the

Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany, likes

looking at these stars because they tend to have unusual properties.

But even by these standards, one star in particular caught his eye:

HIP 13044.

Setiawan and colleagues at Max Planck and the European Space Agency

noticed that the star didn't move at a constant velocity relative to

our sun. Their instruments picked up a regular 16-day pattern, where

sometimes the star was closer and sometimes farther away. That could

be caused by spots on the star, which could confuse velocity

measurements, or by the star expanding and contracting (known as

stellar pulsations).

But the researchers didn't detect

either. That left only one possibility: a planet gravitationally

pulling on the star.

If that's the case, the world is the first foreign planet detected

in the Milky Way, the team reports online today in Science. But

that's not the only unusual thing about it.

It shouldn't have formed

in the first place.

That's because HIP 13044 is a very ancient, very metal-poor star.

It's about 3 billion years older than our own sun and has only 1% as

much metal.

Until now, the prevailing hypothesis has said that as

stars evolve, metals (astronomers' term for any chemical elements

heavier than hydrogen and helium) in the swirling disk around them

form tiny "seeds" that attract other matter and slowly grow into

planets.

So far most surveys have backed up the

theory: Stars rich in metals, such as our Sun, are much more likely

to have planets than stars that don't.

"The fact that you can form planets

around a star that has so little of this material is a very

surprising and unusual thing," says Christopher Johns-Krull, an

astronomer at Rice University in Houston, Texas, who was not

involved in the new work.

But there is a second, more violent,

theory about how planets form.

If the swirling disk of gas is massive

enough - one-tenth the mass of its star or more - Johns-Krull

says the gravitational power of the disk can make the disk unstable.

In those cases, the star isn't big enough to keep the disk in check,

so the disk starts to collapse under its own gravity and forms

planets.

Although it's still not certain that a planet is behind the

variations in the star's speed, all the findings so far point that

way, says NASA astronomer Steven Pravdo. To be sure,

astronomers will need to run other tests.

Ideally, they would look for the planet

to pass in front of the star, but that would work only if the planet

orbits at just the right angle, he says.

"The claim that it's extragalactic

is kind of a guess," says Pravdo.

It's possible the star was originally

part of the Milky Way when it collided with the other galaxy

billions of years ago.

Although an extragalactic planet,

"is a nice possibility," says Pravdo,

the more exciting find is what this planet could do to the idea

of tame, gradual planet formation.

Johns-Krull agrees.

"This planet says, maybe that's not

right," he says. "Maybe it's this other, more dramatic process."

'Alien' Planet Detected Circling Dying Star

by Neil Bowdler

Science reporter, BBC News

18 November 2010

from

BBC Website

This artist's

impression shows HIP 13044 b,

an exoplanet orbiting

a star that entered our galaxy, the Milky Way, from another galaxy

This artist's

impression shows HIP 13044 b,

an exoplanet orbiting

a star that entered the Milky Way from another galaxy

Astronomers claim to have discovered the

first planet originating from outside our galaxy.

The Jupiter-like planet, they say, is part of a solar system which

once belonged to a dwarf galaxy. This dwarf galaxy was in turn

devoured by our own galaxy, the Milky Way, according to a team

writing in the academic journal Science.

The star, called

HIP 13044, is nearing the end of its life and is

2000 light years from Earth.

The discovery was made using a telescope in Chile.

Cosmic cannibalism

Planet hunters have so far netted nearly 500 so-called "exoplanets"

outside our Solar System using various astronomical techniques.

But all of those so far discovered, say the researchers, are

indigenous to our own galaxy, the Milky Way.

This find is different, they say, because the planet circles a sun

which belongs to a group of stars called the "Helmi stream" which

are known to have once belonged to a separate dwarf galaxy.

This galaxy was gobbled up by the Milky Way between six and nine

billion years ago in an act of intergalactic cannibalism.

The

new planet is thought to have a minimum mass 1.25 times that of

Jupiter and circles in close proximity to its parent star, with an

orbit lasting just 16.2 days.

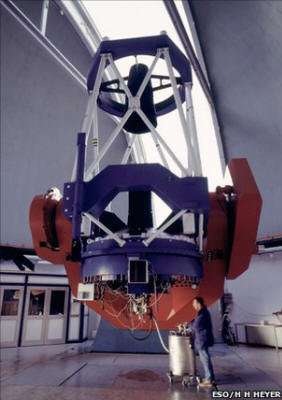

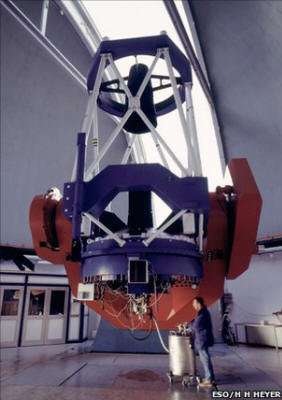

The exoplanet was detected by a European team of astronomers

using

the MPG/ESO 2.2-meter telescope at ESO's La Silla Observatory in

Chile

The exoplanet was detected by a team using the MPG/ESO 2.2-m

telescope in Chile

It sits in the southern

constellation of Fornax.

The planet would have been formed in the early era of its solar

system, before the world was incorporated into our own galaxy, say

the researchers.

"This discovery is very exciting," said Rainer Klement of the Max

Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany, who targeted

the stars in the study.

"For the first time, astronomers have detected a planetary system in

a stellar stream of extragalactic origin. This cosmic merger has

brought an extragalactic planet within our reach."

Dr Robert Massey of the UK's Royal Astronomical Society said the

paper provided the first "hard evidence" of a planet of

extragalactic origin.

"There's every reason to believe that planets are really quite

widespread throughout the Universe, not just in our own galaxy, the

Milky Way, but also in the thousands of millions of others there

are," he said, "but this is the first time we've got hard evidence

of that."

End Days

The new find might also offer us a glimpse of what the final days of

our own Solar System may look like.

HIP 13044 is nearing its end. Having consumed all the hydrogen fuel

in its core, it expanded massively into a "red giant" and might have

eaten up smaller rocky planets like our own Earth in the process,

before contracting.

The new Jupiter-like planet discovered appears to have survived the

fireball, for the moment.

"This discovery is particularly intriguing when we consider the

distant future of our own planetary system, as the Sun is also

expected to become a red giant in about five billion years," said Dr

Johny Setiawan, who also works at the Max Planck Institute for

Astronomy, and who led the study.

"The star is rotating relatively quickly," he said. "One explanation

is that HIP 13044 swallowed its inner planets during the red giant

phase, which would make the star spin more quickly."

The new planet was discovered using what is called the "radial

velocity method" which involves detecting small wobbles in a star

caused by a planet as it tugs on its sun.

These wobbles were picked up using a ground-based telescope at the

European Southern Observatory's

La Silla facility in Chile.

Extragalactic Exoplanet

...Found

Hiding Out in Milky Way

by Ron Cowen

Science News Email Author

November 18, 2010

from

Wired Website

Some extrasolar planets are truly out of

this world.

Astronomers have for the first time

discovered a planet in the Milky Way that came from another galaxy.

The planet, which has a mass of at least 1.25 Jupiters, orbits an

elderly star that was ripped from a small satellite galaxy some 6 to

9 billion years ago.

Johny Setiawan and Rainer Klement of the Max Planck

Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany, describe the finding

online November 18 in Science.

“The coolness factor is definitely

that the planet and star came from another galaxy,” says Sara

Seager of MIT, who was not part of the study. “The planet almost

certainly formed during the time the star was in the other

galaxy.”

In hunting for extrasolar planets,

Setiawan and his colleagues homed in on

HIP 13044, about 2,000 light-years

from Earth, because it’s part of a stream of stars called Helmi,

believed to have originated in another galaxy.

The star’s motion could also be

monitored for many months each year with a spectrograph at the

European Southern Observatory’s La Silla site in Chile, looking for

telltale wobbles that would indicate the tiny tug of an unseen,

orbiting planet.

HIP 13044 and the other stars in the Helmi stream stand out in the

solar neighborhood because they have elongated orbits that take them

about 42,000 light-years above and below the plane of the Milky

Way’s disk. Such orbits strongly suggest the stars were part of a

group torn from a satellite galaxy and stretched out by

gravitational tidal forces into a filament or stream.

The discovery, notes planet hunter Scott Gaudi of Ohio State

University in Columbus,

“is doubly weird: It is a weird

planet around a weird star.”

The star is unusual because it has the

lowest abundance of metals - about 1 percent of the sun’s - of any

star known to have a planet. (In astronomical parlance, a metal

refers to any element heavier than helium.)

The vast majority of the roughly 500

extrasolar planets known are found around stars with a much higher

metal abundance, and the leading theory of planet formation suggests

that stars with high metal contents are those that form giant,

Jupiter-like planets.

Also unusual is that HIP 13044 is old enough to have exhausted its

supply of hydrogen fuel and passed through the red giant phase of

evolution, in which it mushroomed in size. Since then the star

contracted to a diameter about seven times that of the sun and is

now burning helium at its core. A star in this phase of evolution,

known as the red horizontal branch, has never before been found to

have a planet.

In part, that’s because the enhanced activity of old, evolved stars,

including the presence of magnetically driven disturbances known as

starspots, makes it more difficult to discern a stellar wobble, says

Setiawan.

In addition,

“there is a high risk that you will

not find any planets because they have been engulfed by the star

during the [red giant] evolutionary phase,” he adds.

In order to survive, HIP 13044’s planet,

which now resides much closer to the star than Mercury does to the

sun, must have originally orbited at a much greater distance, the

researchers say.

That’s the only way it could have

escaped being swallowed during the time the star was a red giant.

(In several billion years, the sun will also become a puffed-up red

giant and is likely to engulf Earth and the other inner planets.)

Other planets that resided closer to HIP 13044 would not have been

so lucky.

One explanation for the star’s

relatively rapid rate of rotation is that it has been spun up by the

angular momentum of planets it swallowed. Other rapidly rotating,

elderly stars that have evolved to the red horizontal branch may

have had similar dining habits, researchers have previously noted.

Even though the newfound planet has dodged one bullet, it will soon

face another. In a few million years, when the star exhausts all the

helium forged at its core, it will undergo a more rapid and larger

expansion in which the planet is likely to be destroyed.

Planet From Another Galaxy Discovered

by

Best0fScience

November 18, 2010

from

YouTube Website

|

ESOcast is produced

by

ESO, the

European Southern Observatory.

ESO, the European

Southern Observatory, is the pre-eminent

intergovernmental science and technology organization in

astronomy designing, constructing and operating the

world's most advanced ground-based telescopes.

http://www.eso.org/

|

First planet

of extragalactic origin

An exoplanet orbiting a star that entered our galaxy, the Milky Way,

from another galaxy has been detected by a European team of

astronomers using the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope at ESO's

La Silla Observatory in Chile.

The Jupiter-like planet is particularly

unusual, as it is orbiting a star nearing the end of its life and

could be about to be engulfed by it, giving clues about the fate of

our own planetary system in the distant future.

Astronomers have detected nearly 500 planets orbiting stars in our

cosmic neighborhood, but none outside our Milky Way has been

confirmed. Now, however, a planet weighing at least 1.25 times as

much as Jupiter has been discovered orbiting a star of extragalactic

origin, even though the star now finds itself within our own galaxy.

The star, which is known as

HIP 13044, lies about 2000

light-years from Earth and is part of the so-called Helmi stream.

This stream of stars originally belonged to a dwarf galaxy, which

was devoured by our Milky Way in an act of galactic cannibalism six

to nine billion years ago.

Astronomers detected the planet by looking for tiny telltale wobbles

of the star caused by the gravitational tug of an orbiting

companion. For these precise observations, the team used a

high-resolution spectrograph called FEROS, attached to the

2.2-metre telescope at ESO's La Silla Observatory in Chile.

The planet, HIP 13044 b, is also one of the few exoplanets known to

have survived its host star massively growing in size after

exhausting the hydrogen fuel supply in its core - the Red Giant

phase of stellar evolution.

HIP 13044 b is near to its host star. At the closest point in its

elliptical orbit, it is less than one stellar diameter from the

surface of the star (or 0.055 times the Sun-Earth distance). and

completes an orbit in only about 16 days. The astronomers

hypothesize that the planet's orbit might initially have been much

larger, but that it moved inwards during the

Red Giant phase.

Any closer-in planets may not have been so lucky. Astronomers

suggest that some inner planets may have been swallowed by the star

during the Red Giant phase.

Although the Jupiter-like exoplanet has escaped the fate of these

inner planets so far, the star will expand again in the next stage

of its evolution. When this happens, the star may engulf the planet,

meaning it may be doomed after all.

The astronomers are now searching for more planets around stars near

the ends of their lives.

Their work may tell us about the fate of

planets in the distant future of our own Solar System, as the Sun is

also expected to become a Red Giant in about five billion years.

|