|

|

|

September 10, 2013

from

ModernFarmer Website

NASA looks to grow fresh veggies,

230 miles above the Earth

Last year, an astronaut named Don Pettit began an unusual writing project on NASA’s website. Called "Diary of a Space Zucchini," the blog took the perspective of an actual zucchini plant on the International Space Station (ISS).

Entries were insightful and strange, poignant and poetic.

An unorthodox use of our tax dollars, but before you snicker, consider this:

If - as some doomsday scientists predict - we eventually exhaust the Earth’s livability, space farming will prove vital to the survival of our species. Around the world, governments and private companies are doing research on how we are going to grow food on space stations, in spaceships, even on Mars.

Mars Society farming

The Mars Society is testing a greenhouse in a remote corner of Utah, researchers at the University of Gelph in Ontario are looking at long-term crops like soybeans and barley and Purdue University scientists are marshaling vertical garden design for space conditions.

Perhaps most importantly, though, later this year NASA will be producing its own food in orbit for the first time ever.

And if space farming still seems like a pipe dream, the zucchini also served a more tangible purpose. It kept Pettit and his crewmates sane.

You Can Eat It, Too

Growing food in space helps solve one of the biggest issues in space travel: the price of eating.

It costs roughly $10,000 a pound to send food to the ISS, according to Howard Levine, project scientist for NASA’s International Space Station and Spacecraft Processing Directorate.

There’s a premium on densely caloric foods with long shelf lives. Supply shuttles carry such limited fresh produce that Gioia Massa, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA, says astronauts devour it almost immediately.

Levine and Massa are part of the team developing the Vegetable Production System (VEGGIE) program, set to hit the ISS later this year.

This December, NASA plans to launch a set of Kevlar pillow-packs, filled with a material akin to kitty litter, functioning as planters for six romaine lettuce plants. The burgundy-hued lettuce (NASA favors the "Outredgeous" strain) will be grown under bright-pink LED lights, ready to harvest after just 28 days.

NASA has a long history of testing plant growth in space, but the goals have been largely academic.

Experiments have included figuring out the effects of zero-gravity on plant growth, testing quick-grow sprouts on shuttle missions and assessing the viability of different kinds of artificial light.

But VEGGIE is NASA’s first attempt to grow produce that could actually sustain space travelers.

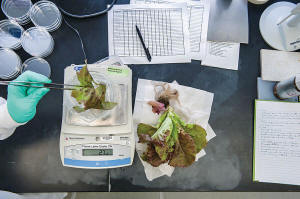

testing lab at Kennedy Space Center.

Naturally, the dream is to create a regenerative growth system, so food could be continually grown on the space station - or, potentially, on moon colonies or Mars.

The Outredgeous lettuce is slated as a first-phase vegetable, quick to grow and loaded with antioxidants (a potential antidote for cosmic radiation). Later veggies may include radishes, snap peas and a special strain of tomato, designed to take up minimal space.

Plant size is a vital calculation in determining what to grow on the space station, where every square foot is carefully allotted.

Harvest time is also of extreme importance; the program wants to maximize growth cycles within each crew’s (on average) six-month stay.

Leafy greens are ideal, ready to be consumed as soon as they’re plucked from the soil.

Potatoes or sweet potatoes, not very good raw, fall into what Massa calls "midterm level" - plants NASA may test further down the line. The most outlandish crops would be wheat and rice, taking longer to grow and requiring bulky milling equipment. Clearly, plants that need processing make less attractive candidates for space travel.

Levine says NASA has tested strains of quick-growing dwarf wheat on past space missions.

But growing this kind of crop on a large scale, with the intention of providing long-term sustenance, is still a ways off.

A Garden for Major Tom

But the plants aren’t just for eating - they act as a form of emotional sustenance called horticultural therapy. It’s based on the simple idea that plant care is a balm for the human psyche.

According to the Horticultural Society of New York, which has practiced this therapy with Rikers Island inmates since 1989, the list of gains is long: "stress reduction, mood improvement, alleviation of depression, social growth, physical and mental rehabilitation" and general wellness.

Naturally, these benefits are highly prized in space, where even the sturdiest astronauts may be pushed to their limits.

During this six-month stay Pettit brought the space zucchini up with "two new crewmates" - broccoli and sunflower plants - as a personal project. He didn’t have fancy equipment, and only a little soil.

He gave the plants sun by shuttling them between space station windows, and grew them in a plastic bag, feeding them a liquid made from composted food scraps.

The crew never tried eating the plants; Pettit jokes it would have felt like cannibalism.

Massa thinks VEGGIE could promise similar psychic gains to space station astronauts.

For one thing, there’s the splash of color provided by the sanguine plants, chromatic relief in a sea of whites and beiges. The program’s second phase will include flowering zinnias, for even more visual vibrancy.

Not to mention, caring for plants can conjure up unknowable associative memories.

A childhood harvest, perhaps, or a forgotten summer stroll through the garden.

Waiting Is the Hardest Part

The first batch of space-ready lettuce is something of a tease for the NASA crew - once harvested, it will be frozen and stored away for testing back on Earth. No one is allowed to eat anything before the plants are thoroughly vetted for cosmic microbes.

These space germs are often fairly benign, akin to the natural bacteria that build up in any moist root bank.

Russian crews are allowed to consume vegetables grown on their side of the space station, but microbe standards are strict and unwavering on U.S. space missions. Massa says NASA’s surgeons set these levels based simply on quantity, without regard for "good" or "bad" germs.

After the first lettuce harvest is tested, she hopes for reevaluation of the microbial standards, with specific dispensations for agriculture.

But once that hurdle is cleared, Massa has high hopes for the program. Her team has been testing the system in NASA labs since 2011, working out the bugs and evaluating the technology.

The growth chambers themselves, created by the Wisconsin company Orbital Technologies Corporation (ORBITEC), are lightweight and easily stored, with relatively simple watering and lighting systems.

Each unit requires little space, but could easily be replicated on a large scale. And unlike its clunky, power-draining predecessors, the whole setup requires about as much energy as a desktop computer.

As space travel becomes increasing a public-private partnership, NASA is not alone in testing out food programs.

Mike Dixon is a professor at the University of Guelph in Ontario, and his program is looking at the viability of longer-term crops, like soybeans. Other efforts are focusing on vertical farming design; some researchers are replicating Mars-like conditions on Earth, like the South Pole.

For Massa, this is the realization of a decades-old dream.

As a teenager in Florida, she was both a member of her local Future Farmers of America chapter and - like many kids of the ’80s - a space superfan. Her career path was shaped early by a teacher of hers who attended a NASA educational program called "Energize the Green Machine," speculating on the future of space farming.

Now, after devoting a life to getting here, Massa is on the brink of space farming’s launch.

She mulls over the implications.

***

|