|

October 6, 2011

The comet Elenin, a subject of intense Internet discussion for several months, seems to have disappointed everyone.

I speak here not just of the doomsayers,

who were awaiting a frightful specter in recent weeks. You might

think these folks would be happy that the celebrated intruder faded

fast just when it was supposed to be reaching maximum activity. But

in these strange times, Doomsday seems a lot more fun than a minor

distraction in our cosmic neighborhood.

But is that really all we should be discussing here?

Elenin has only one connection to “Doomsday.” Like every comet, it reminds us of ancient memories of a truly terrifying and destructive Great Comet, the true source of comet fears and Doomsday anxiety - a verifiable cultural conditioning that has persisted for thousands of years.

With every appearance of a comet the

ancient fear resurfaces, but this fact adds nothing to scientific

discussion of Elenin and its fate.

From the beginning, the Nibiru concept

promoted by Sitchin was a meaningless fiction. A few meager examples

of the word exist in Babylonian literature. Nothing in the language

suggests either a comet or the rogue planet claimed by Sitchin.

The ignored fact is that Elenin has only

added to the list of comet “misbehavior” - throwing a spotlight once

again on mistaken theoretical assumptions.

It will certainly not serve the

interests of scientific progress to ignore the question posed or

turn away from an essential reconsideration of theory.

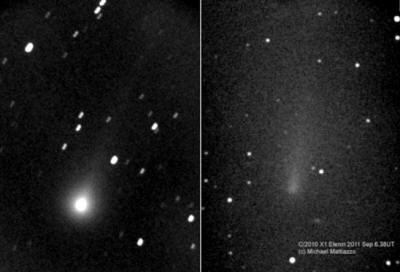

Then something unexpected happened when, on August 19, the charged particles of a coronal mass ejection struck the comet. In response, the comet flared up dramatically, as seen in the image on the left below.

This image was recorded by amateur astronomer Michael Mattiazzo, and cited on the website Astroblog.

Amateur astronomer Michael Mattiazzo (Castlemaine, Australia) captured images of comet Elenin on Aug. 19 (left) after the nucleus was struck by a CME. The greatly diminished display on the right was captured on Sept. 6, 2011. Astronomers view the second image as an indication of disintegration. CREDIT: Michael Mattiazzo

Ian Musgrave writes,

But over the next few days observers

reported a huge decrease in the intensity of the comet, and it

appeared that the comet was falling apart.

But did the specialists see a clue in this electrical event?

Did anyone remember how, in October 2007, comet Holmes began discharging explosively, brightening by a factor of a million after it was subjected to a huge spike in the solar wind, eventually producing a spectacular coma larger than the diameter of the Sun. The event occurred as Holmes moved away from the Sun, leaving stunned astronomers to offer wild guesses about the cause.

No mention of any connection to the surge of charged particles from the Sun, since electrical causes are so clearly outside the astronomers’ field of view.

showing the blue ion tail on the right,taken from Hungary.

CREDIT: Ivan Eder. Least of all did the the scientific media recall how, in 1991, comet Halley flared up to 300 times its normal brightness while on its long journey away from the Sun, in the distant realm between the orbits of Saturn and Uranus.

Here, a surface temperature of -200 ˚C

would categorically exclude all “cometary” activity” under standard

assumptions. Was it a coincidence that this occurred in the wake of

near-record solar outbursts?

If astronomers are correct in viewing comets as chunks of icy material moving through an electrically neutral domain of the Sun, imagine the absurdity of thinking that “warming” from the Sun - starting in the icy region beyond the asteroid belt! - could have caused Elenin to evaporate completely within a few months later, while only spending a few weeks inside Earth’s orbit.

This is the one issue on which the

standard model and the electric model deliver the same message:

Elenin’s size was greatly overestimated.

At that distance from the Sun, where any

appreciable effect of sublimation is doubtful, how did it create the

illusion of a respectable size?

Some comets we can visit because they have short periods and we know where they are. But when seen electrically these comets cannot give us an accurate picture of comets as a whole. Electric comets imply that the Sun is the center of an electric field. It is the most positively charged body in the solar system. A comet approaching the Sun from a much more distant region will carry far more negative charge than those orbiting closer to the Sun.

And this is why comparisons based on

size or strength of cometary activity alone, without reference to

orbital characteristics, have never held up and never will.

As electric arcs to the surface

excavated material, accelerating it into a highly diffuse dust

cloud, Elenin began to display a coma. That, not any imagined

“thermal effects,” was why Leonid Elenin detected the tiny comet in

December 2010, when it was well beyond the asteroid belt.

Electrical

breakdown occurred and the nucleus shattered like an exploding

capacitor - just as we’ve seen in the case of other “inexplicable,”

exploding comets.

Elenin is not a “sun grazer.” Its perihelion (closest approach to the Sun) was outside the orbit of Mercury. But what if Elenin was, in truth, a tiny comet, but a strongly charged body for its size? As noted above, since Elenin arrived from a very remote region, electrically-provoked brightening would be expected as it entered a more positively charged region of the heliosphere.

For the same reasons, under the impact of a CME, disintegration by electrical breakdown is the obvious interpretation of what occurred.

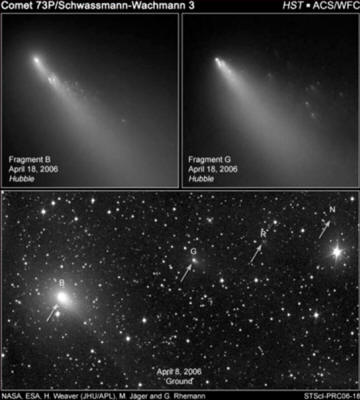

The upper frame of this Hubble Space Telescope image captures the explosive disintegration of two separate fragments of Comet Schwassman-Wachmann 3 in April, 2006. The relationship of these two fragments to two other fragments

from earlier break-up

is evident in the lower Hubble image. Would a larger comet have disintegrated so completely following the electrical explosion?

For comparison purposes, the progressive disintegration of the unpredictable Comet Schwassmann-Wachmann 3 is worth noting.

In the image above, the Hubble Space Telescope

captured the disintegration of Schwassmann-Wachmann 3 in progress,

when it was still out beyond Earth’s orbit. Apparently, in this case a comet of more

“respectable” size than Elenin exploded into fragments through

phases, in the course of two or three orbits, leading to sudden,

rapid disintegration of at least two larger fragments in April,

2006.

The prolonged disintegration of Comet

Schwassman-Wachmann simply underscores the point noted above, that

Elenin’s disintegration in a bright flash, followed by rapid

disappearance of the residue, is the confirmation of a tiny nucleus.

Indeed, Linear’s entry into the inner solar system from the outermost regions, its highly eccentric orbit, its brightening, and its demise appear to have anticipated very well the story of Elenin.

Compare the two images below to the “before and after” images of Elenin given earlier in this article.

Comet Linear on July 23, 2000, in its “brightest moment” before complete disintegration.

http://www.ing.iac.es/PR/AR2000/high_2000.html

after fragmentation

of the nucleus Comet Linear also provided one other clue to the electric comet.

Rocky pebbles and grains of dust can quickly adjust to their electrical environment. With complete disintegration, discharge activity will quickly end. That’s what happened to Linear, and very likely what happened to Elenin. Linear was neither a dirty snowball, nor an icy dirtball. With its disintegration, the only appreciable residue was dry dust.

In other words, though occasional water ice or other volatiles on a comet cannot be categorically excluded, there is good reason to anticipate that the remains of Comet Elenin will be almost entirely dust.

(This will most likely mean that the

only “water” in the dust cloud will be the consequence of negatively

charged oxygen atoms from the comet combining with hydrogen ions

from the solar wind.)

When Donald Brownlee, head of NASA’s stardust mission, confessed,

...he was simply speaking with the candor that all comet specialists owe to the tax-paying public.

Today, in the face of growing public disinterest, this candor is needed more than ever. A comet holding its integrity year after year, then suddenly shattering at considerable distances from the Sun, was never expected.

But what better way to move science forward than to ask:

|