|

|

|

from GBN Website recovered through WayBackMacine Website

Letter from Judith

Rodin

Letter from Peter Schwartz

Introduction

Whether it is a community mobile phone, a solar panel, a new farming practice, or a cutting-edge medical device, technology is altering the landscape of possibility in places where possibilities used to be scarce. And yet looking out to the future, there is no single story to be told about how technology will continue to help shape - or even revolutionize - life in developing countries.

There are many possibilities, some good and some less so, some known and some unknowable.

Indeed, for everything we think we

can anticipate about how technology and international development will

interact and intertwine in the next 20 years and beyond, there is so much

more that we cannot yet even imagine.

Given the uncertainty about,

The Rockefeller Foundation believes that in order to understand the many ways in which technology will impact international development in the future, we must first broaden and deepen our individual and collective understanding of the range of possibilities.

This report, and the project upon which it is

based, is one attempt to do that. In it, we share the outputs and insights

from a year-long project, undertaken by the Rockefeller Foundation and

Global Business Network (GBN), designed to explore the role of technology in

international development through scenario planning, a methodology in which

GBN is a long-time leader.

In 2009, the Institute for Alternative Futures published the report Foresight for Smart Globalization - Accelerating and Enhancing Pro-Poor Development Opportunities, with support from the Rockefeller Foundation.

That effort was a reflection of the Foundation's strong commitment to exploring innovative processes and embracing new pathways for insight aimed at helping the world's poor.

With this report, the Foundation takes a further

step in advancing the field of pro-poor foresight, this time through the

lens of scenario planning.

While not a comprehensive list, the following readings offer additional insights on this topic.

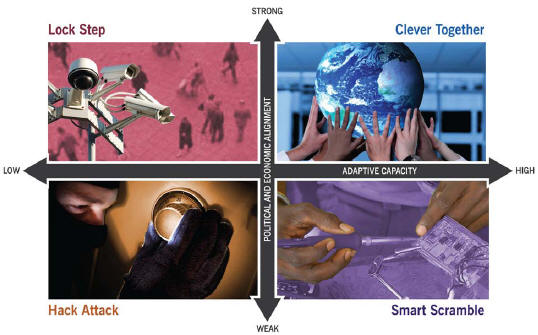

The Scenario Framework

These forces were generated through both secondary research and in-depth interviews with Foundation staff, Foundation grantees, and external experts. Next, all these constituents came together in several exploratory workshops to further brainstorm the content of these forces, which could be divided into two categories: predetermined elements and critical uncertainties.

A good starting point for any set of scenarios is to understand those driving forces that we can be reasonably certain will shape the worlds we are describing, also known as "predetermined elements."

For example, it is a near geopolitical certainty that - with the rise of China, India, and other nations - a multi-polar global system is emerging.

One demographic certainty is that global

population growth will continue and will put pressure on energy, food, and

water resources - especially in the developing world. Another related

certainty: that the world will strive to source more of its energy from

renewable resources and may succeed, but there will likely still be a

significant level of global interdependence on energy.

Rather, scenarios are formed around

"critical

uncertainties" - driving forces that are considered both highly important to

the focal issue and highly uncertain in terms of their future resolution.

Whereas predetermined elements are predictable driving forces, uncertainties

are by their nature unpredictable: their outcome can be guessed at but not

known.

The scenario framework provides a structured way to consider how these critical uncertainties might unfold and evolve in combination.

Identifying the two most important uncertainties guarantees

that the resulting scenarios will differ in ways that have been judged to be

critical to the focal question.

In 2012, the pandemic that the world had been anticipating for years finally hit.

Unlike 2009's H1N1, this new influenza strain - originating from wild geese - was extremely virulent and deadly.

Even the most pandemic-prepared nations were quickly overwhelmed when the virus streaked around the world, infecting nearly 20 percent of the global population and killing 8 million in just seven months, the majority of them healthy young adults.

The pandemic also had a deadly effect on economies:

The pandemic blanketed the planet - though disproportionate numbers died in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Central America, where the virus spread like wildfire in the absence of official containment protocols. But even in developed countries, containment was a challenge.

The United States' initial policy of "strongly discouraging" citizens from flying proved deadly in its leniency, accelerating the spread of the virus not just within the U.S. but across borders.

However, a few countries did fare better - China in particular.

The Chinese government's quick imposition and enforcement of mandatory quarantine for all citizens, as well as its instant and near-hermetic sealing off of all borders, saved millions of lives, stopping the spread of the virus far earlier than in other countries and enabling a swifter post- pandemic recovery.

Even after the pandemic faded, this more

authoritarian control and oversight of citizens and their activities stuck

and even intensified. In order to protect themselves from the spread of

increasingly global problems - from pandemics and transnational terrorism to

environmental crises and rising poverty - leaders around the world took a

firmer grip on power.

Citizens willingly gave up some of their sovereignty - and their privacy - to more paternalistic states in exchange for greater safety and stability. Citizens were more tolerant, and even eager, for top-down direction and oversight, and national leaders had more latitude to impose order in the ways they saw fit.

In developed countries, this heightened oversight took many forms:

In many developed countries, enforced

cooperation with a suite of new regulations and agreements slowly but

steadily restored both order and, importantly, economic growth.

Top-down authority took different forms in different countries, hinging largely on the capacity, caliber, and intentions of their leaders. In countries with strong and thoughtful leaders, citizens' overall economic status and quality of life increased. In India, for example, air quality drastically improved after 2016, when the government outlawed high-emitting vehicles.

In Ghana, the introduction of ambitious government programs to improve basic infrastructure and ensure the availability of clean water for all her people led to a sharp decline in water-borne diseases.

But more authoritarian leadership worked less well -

and in some cases tragically - in countries run by irresponsible elites who

used their increased power to pursue their own interests at the expense of

their citizens.

In the developing world, access to "approved" technologies increased but beyond that remained limited:

Some governments found this patronizing and

refused to distribute computers and other technologies that they scoffed at

as "second hand." Meanwhile, developing countries with more resources and

better capacity began to innovate internally to fill these gaps on their

own.

Scientists and innovators were often told by governments what research lines to pursue and were guided mostly toward projects that would make money (e.g., market-driven product development) or were "sure bets" (e.g., fundamental research), leaving more risky or innovative research areas largely untapped.

Well-off countries and monopolistic companies with big research and development budgets still made significant advances, but the IP behind their breakthroughs remained locked behind strict national or corporate protection.

Russia and India imposed stringent domestic standards for supervising and certifying encryption-related products and their suppliers - a category that in reality meant all IT innovations.

The U.S. and EU struck back with retaliatory national standards, throwing a wrench in the development and diffusion of technology globally.

"IT IS POSSIBLE TO DISCIPLINE AND CONTROL SOME SOCIETIES FOR SOME TIME,

BUT NOT THE WHOLE WORLD

ALL THE TIME." Leading Edge, India

Especially in the developing world, acting in one's national self-interest often meant seeking practical alliances that fit with those interests - whether it was gaining access to needed resources or banding together in order to achieve economic growth.

In South America and Africa, regional and sub-regional alliances became more structured.

Kenya doubled its trade with southern and eastern Africa, as new partnerships grew within the continent. China's investment in Africa expanded as the bargain of new jobs and infrastructure in exchange for access to key minerals or food exports proved agreeable to many governments. Cross-border ties proliferated in the form of official security aid.

While the deployment of foreign security teams

was welcomed in some of the most dire failed states, one-size-fits-all

solutions yielded few positive results.

Sporadic pushback became increasingly organized and coordinated, as disaffected youth and people who had seen their status and opportunities slip away - largely in developing countries - incited civil unrest. In 2026, protestors in Nigeria brought down the government, fed up with the entrenched cronyism and corruption.

Even those who liked the greater stability and predictability of this world began to grow uncomfortable and constrained by so many tight rules and by the strictness of national boundaries.

The feeling lingered that sooner or later, something would inevitably upset the neat order that the world's governments had worked so hard to establish.

ROLE OF PHILANTHROPY IN LOCK STEP

Given the strong role of governments, doing philanthropy will require heightened diplomacy skills and the ability to operate effectively in extremely divergent environments. Philanthropy grantee and civil society relationships will be strongly moderated by government, and some foundations might choose to align themselves more closely with national official development assistance (ODA) strategies and government objectives.

Larger philanthropies will retain an outsized

share of influence, and many smaller philanthropies may find value in

merging financial, human, and operational resources.

Many governments will place severe restrictions

on the program areas and geographies that international philanthropies can

work in, leading to a narrower and stronger geographic focus or grant-making

in their home country only.

TECHNOLOGY IN LOCK STEP

While there is no way of accurately predicting what the important technological advancements will be in the future, the scenario narratives point to areas where conditions may enable or accelerate the development of certain kinds of technologies.

Thus for each scenario we offer a sense of the

context for technological innovation, taking into consideration the pace,

geography, and key creators. We also suggest a few technology trends and

applications that could flourish in each scenario.

Most technological improvements are created by

and for developed countries, shaped by governments' dual desire to control

and to monitor their citizens. In states with poor governance, large-scale

projects that fail to progress abound.

Manisha gazed out on the Ganges River, mesmerized by what she saw.

Back in 2010, when she was 12 years old, her parents had brought her to this river so that she could bathe in its holy waters. But standing at the edge, Manisha had been afraid. It wasn't the depth of the river or its currents that had scared her, but the water itself: it was murky and brown and smelled pungently of trash and dead things.

Manisha had balked, but her mother had pushed her forward, shouting that this river flowed from the lotus feet of Vishnu and she should be honored to enter it. Along with millions of Hindus, her mother believed the Ganges's water could cleanse a person's soul of all sins and even cure the sick.

So Manisha had grudgingly dunked herself in the

river, accidentally swallowing water in the process and receiving a bad case

of giardia, and months of diarrhea, as a result.

It was now 2025. Manisha was 27 years old and a manager for the Indian government's Ganges Purification Initiative (GPI). Until recently, the Ganges was still one of the most polluted rivers in the world, its coliform bacteria levels astronomical due to the frequent disposal of human and animal corpses and of sewage (back in 2010, 89 million liters per day) directly into the river.

Dozens of organized attempts to clean the Ganges over the years had failed. In 2009, the World Bank even loaned India $1 billion to support the government's multi-billion dollar cleanup initiative. But then the pandemic hit, and that funding dried up.

But what didn't dry up was the government's

commitment to cleaning the Ganges - now not just an issue of public health

but increasingly one of national pride.

Many lives in her home city of Jaipur had been saved by the government's quarantines during the pandemic, and that experience, thought Manisha, had given the government the confidence to be so strict about river usage now:

Discarding ritually burned bodies in the Ganges was now illegal, punishable by years of jail time. Companies found to be dumping waste of any kind in the river were immediately shut down by the government.

There were also severe restrictions on where

people could bathe and where they could wash clothing. Every 20 meters along

the river was marked by a sign outlining the repercussions of "disrespecting

India's most treasured natural resource." Of course, not everyone liked it;

protests flared every so often. But no one could deny that the Ganges was

looking more beautiful and healthier than ever.

Her favorite were the submersible bots that continuously "swam" the river to detect, through sensors, the presence of chemical pathogens.

New riverside filtration systems that sucked in dirty river water and spit out far cleaner water were also impressive - especially because on the outside they were designed to look like mini-temples.

In fact, that's why Manisha was at the river today, to oversee the installation of a filtration system located not even 100 feet from where she first stepped into the Ganges as a girl. The water looked so much cleaner now, and recent tests suggested that it might even meet drinkability standards by 2035.

Manisha was tempted to kick off her shoe and dip

her toe in, but this was a restricted area now - and she, of all people,

would never break that law.

The recession of 2008-10 did not turn into the decades-long global economic slide that many had feared.

In fact, quite the opposite: strong global growth returned in force, with the world headed once again toward the demographic and economic projections forecasted before the downturn.

India and China were on track to see their middle classes explode to 1 billion by 2020.

Mega-cities like Sao Paulo and Jakarta expanded

at a blistering pace as millions poured in from rural areas. Countries raced

to industrialize by whatever means necessary; the global marketplace

bustled.

Undeniably, the planet's climate was becoming increasingly unstable.

Sea levels were rising fast, even as countries continued to build-out coastal mega-cities.

In 2014, the Hudson River overflowed into New York City during a storm surge, turning the World Trade Center site into a three-foot-deep lake. The image of motorboats navigating through lower Manhattan jarred the world's most powerful nations into realizing that climate change was not just a developing-world problem.

That same year, new measurements showing that

atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were climbing precipitously created new

urgency and pressure for governments (really, for everyone) to do something

fast.

But highly coordinated worldwide strategies for

addressing such urgent issues just might. What was needed was systems

thinking - and systems acting - on a global scale.

In 2015, a critical mass of middle income and developed countries with strong economic growth publicly committed to leveraging their resources against global-scale problems, beginning with climate change. Together, their governments hashed out plans for monitoring and reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the short term and improving the absorptive capacity of the natural environment over the long term.

In 2017, an international agreement was reached on carbon sequestration (by then, most multinational corporations had a chief carbon officer) and intellectual and financial resources were pooled to build out carbon capture processes that would best support the global ecosystem. A functioning global cap and trade system was also established.

Worldwide, the pressure to reduce waste and increase efficiency in planet-friendly ways was enormous.

New globally coordinated systems for monitoring

energy use capacity - including smart grids and bottom-up pattern

recognition technologies - were rolled out. These efforts produced real

results: by 2022, new projections showed a significant slowing in the rise

of atmospheric carbon levels.

Enormous, benign "surveillance" systems allowed citizens to access data - all publicly available - in real time and react. Nation-states lost some of their power and importance as global architecture strengthened and regional governance structures emerged. International oversight entities like the UN took on new levels of authority, as did regional systems like the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD), and the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

The worldwide spirit of collaboration also

fostered new alliances and alignments among corporations, NGOs, and

communities.

Companies, NGOs, and governments - often acting together - launched pilot programs and learning labs to figure out how to best meet the needs of particular communities, increasing the knowledge base of what worked and what didn't.

Pharmaceuticals giants released thousands of

drug compounds shown to be effective against diseases like malaria into the

public domain as part of an "open innovation" agenda; they also opened their

archives of R&D on neglected diseases deemed not commercially viable,

offering seed funding to scientists who wanted to carry the research

forward.

Better food distribution was also high on the agenda, and more open markets and south-south trade helped make this a reality. In 2022, a consortium of nations, NGOs, and companies established the Global Technology Assessment Office, providing easily accessible, real-time information about the costs and benefits of various technology applications to developing and developed countries alike.

All of these efforts translated into real

progress on real problems, opening up new opportunities to address the needs

of the bottom billion - and enabling developing countries to become engines

of growth in their own right.

Improved infrastructure accelerated the greater mobility of both people and goods, and urban and rural areas got better connected. In Africa, growth that started on the coasts spread inward along new transportation corridors. Increased trade drove the specialization of individual firms and the overall diversification of economies.

In many places, traditional social barriers to overcoming poverty grew less relevant as more people gained access to a spectrum of useful technologies - from disposable computers to do-it-yourself (DIY) windmills.

"WHAT IS OFTEN SURPRISING ABOUT NEW TECHNOLOGIES IS COLLATERAL DAMAGE: THE EXTENT OF THE PROBLEM THAT YOU CAN CREATE

BY SOLVING ANOTHER

PROBLEM IS ALWAYS A BIT OF A SURPRISE." Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH)

Given the circumstances that forced these new heights of global cooperation and responsibility, it was no surprise that much of the growth in the developing world was achieved more cleanly and more "greenly."

In Africa, there was a big push for solar energy, as the physical geography and low population density of much of the continent enabled the proliferation of solar farms.

The Desertec initiative to create massive thermal electricity plants to supply both North Africa and, via undersea cable lines, Southern Europe was a huge success. By 2025, a majority of electricity in the Maghreb was coming from solar, with exports of that power earning valuable foreign currency.

The switch to solar created new "sun" jobs,

drastically cut CO2 emissions, and earned governments billions

annually. India exploited its geography to create similar "solar valleys"

while decentralized solar-powered drip irrigation systems became popular in

sub-Saharan Africa.

Regional

integration through

COMESA (the Common Market for Eastern and

Southern Africa) and other institutions allowed member nations to better

organize to meet their collective needs as consumers and increasingly as

producers.

But the world was far from perfect. There were still failed states and places with few resources.

Moreover, such rapid progress had created new problems. Rising consumption standards unexpectedly ushered in a new set of pressures: the improved food distribution system, for example, generated a food production crisis due to greater demand. Indeed, demand for everything was growing exponentially.

By 2028, despite ongoing efforts to guide

"smart

growth," it was becoming clear that the world could not support such rapid

growth forever.

Operationally, this is a "virtual model" world in which philanthropies use all of the tools at their disposal to reinforce and bolster their work. With partnerships and networks increasingly key, philanthropies work in a more virtual way, characterized by lots of wikis, blogs, workspaces, video conferences, and virtual convenings.

Smaller philanthropies proliferate, with a

growing number of major donors emerging from the developing world.

There are considerable flows of talent between

the for-profit and nonprofit sectors, and the lines between these types of

organizations become increasingly blurred.

Trade and foreign direct investment spread technologies in all directions and make products cheaper for people in the developing world, thereby widening access to a range of technologies.

The

atmosphere of cooperation and transparency allows states and regions to

glean insights from massive datasets to vastly improve the management and

allocation of financial and environmental resources.

LIFE IN CLEVER TOGETHER

This wasn't just any steak. It was research.

Alec and his research team had been working for months to fabricate a new meat product - one that tasted just like beef yet actually contained only 50 percent meat; the remaining half was a combination of synthetic meat, fortified grains, and nano-flavoring. Finding the "right" formula for that combo had kept the lab's employees working around the clock in recent weeks.

And judging from the look on Alec's face, their work wasn't over.

As Alec watched his team scramble back to their lab benches, he felt confident that it wouldn't be long before they would announce the invention of an exciting new meat product that would be served at dinner tables everywhere.

And, in truth, Alec's confidence was very well founded. For one, he had the world's best and brightest minds in food science from all over the world working together right here in his lab.

He also had access to seemingly infinite amounts

of data and information on everything from global taste preferences to meat

distribution patterns - and just a few touches on his lab's research screens

(so much easier than the clunky computers and keyboards of the old days)

gave him instant access to every piece of research ever done in meat science

or related fields from the 1800s up through the present (literally the

present - access to posted scientific research was nearly instantaneous,

delayed by a mere 1.3 seconds).

As a result, scientists were making real

progress in addressing planet-wide problems that had previously seemed so

intractable: people were no longer dying as frequently from preventable

diseases, for example, and alternative fuels were now mainstream.

The demand for meat, in particular, was rising, but adding more animals to the planet created its own set of problems, such as more methane and spiking water demand.

And that's where Alec saw both need and opportunity: why not make the planet's meat supply go further by creating a healthier alternative that contained less real meat?

That was fast, thought Alec, as he searched

around his desk for the fork.

Devastating shocks like September 11, the Southeast Asian tsunami of 2004, and the 2010 Haiti earthquake had certainly primed the world for sudden disasters.

But no one was prepared for a world in which large-scale catastrophes would occur with such breathtaking frequency.

The years 2010 to 2020 were dubbed the "doom decade" for good reason:

Not surprisingly, this opening series of deadly asynchronous catastrophes (there were more) put enormous pressure on an already overstressed global economy that had entered the decade still in recession.

Massive humanitarian relief efforts cost vast sums of money, but the primary sources - from aid agencies to developed-world governments - had run out of funds to offer.

Most nation-states could no longer afford their locked-in costs, let alone respond to increased citizen demands for more security, more healthcare coverage, more social programs and services, and more infrastructure repair.

In 2014, when mudslides in Lima buried thousands, only minimal help trickled in, prompting the Economist headline:

These dire circumstances forced tough tradeoffs.

In 2015, the U.S. reallocated a large share of its defense spending to domestic concerns, pulling out of Afghanistan - where the resurgent Taliban seized power once again. In Europe, Asia, South America, and Africa, more and more nation-states lost control of their public finances, along with the capacity to help their citizens and retain stability and order.

Resource scarcities and trade disputes, together with severe economic and climate stresses, pushed many alliances and partnerships to the breaking point; they also sparked proxy wars and low-level conflict in resource-rich parts of the developing world.

Nations raised trade barriers in order to protect their domestic sectors against imports and - in the face of global food and resource shortages - to reduce exports of agricultural produce and other commodities.

By 2016, the global coordination and interconnectedness that had marked the post-Berlin Wall world was tenuous at best. With government power weakened, order rapidly disintegrating, and safety nets evaporating, violence and crime grew more rampant.

Countries with ethnic, religious, or class divisions saw especially sharp spikes in hostility:

Meanwhile, overtaxed militaries and police forces could do little to stop growing communities of criminals and terrorists from gaining power.

Technology-enabled gangs and networked criminal enterprises exploited both the weakness of states and the desperation of individuals. With increasing ease, these "global guerillas" moved illicit products through underground channels from poor producer countries to markets in the developed world.

Using retired 727s and other rogue aircraft, they crisscrossed the Atlantic, from South America to Africa, transporting cocaine, weapons, and operatives.

Drug and gun money became a common recruiting tool for the desperately poor. Criminal networks also grew highly skilled at counterfeiting licit goods through reverse engineering. Many of these "rip-offs" and copycats were of poor quality or downright dangerous.

In the context of weak health systems, corruption, and inattention to standards - either within countries or from global bodies like the World Health Organization - tainted vaccines entered the public health systems of several African countries.

In 2021, 600 children in Cote d'Ivoire died from a bogus Hepatitis B vaccine, which paled in comparison to the scandal sparked by mass deaths from a tainted anti-malarial drug years later.

The deaths and resulting scandals sharply

affected public confidence in vaccine delivery; parents not just in Africa

but elsewhere began to avoid vaccinating their children, and it wasn't long

before infant and child mortality rates rose to levels not seen since the

1970s.

Desperate to protect themselves and their intellectual property, the few multinationals still thriving enacted strong, increasingly complex defensive measures. Patent applications skyrocketed and patent thickets proliferated, as companies fought to claim and control even the tiniest innovations.

Security measures and screenings tightened.

Blockbuster pharmaceuticals quickly became artifacts of the past, replaced by increased production of generics. Breakthrough innovations still happened in various industries, but they were focused more on technologies that could not be easily replicated or re-engineered.

And once created, they were vigorously guarded by their inventors - or even by their nations.

In 2022, a biofuel breakthrough in Brazil was protected as a national treasure and used as a bargaining chip in trade with other countries.

"WE HAVE THIS LOVE AFFAIR WITH STRONG CENTRAL STATES, BUT THAT'S NOT THE ONLY POSSIBILITY. TECHNOLOGY IS GOING TO MAKE THIS EVEN MORE REAL FOR AFRICA. THERE IS THE SAME CELLPHONE PENETRATION RATE IN SOMALIA AS IN RWANDA.

IN THAT RESPECT, SOMALIA

WORKS." Society for International Development, Tanzania

Verifying the authenticity of anything was increasingly difficult.

The heroic efforts of several companies and NGOs to create recognized seals of safety and approval proved ineffective when even those seals were hacked.

The positive effects of the mobile and Internet revolutions were tempered by their increasing fragility as scamming and viruses proliferated, preventing these networks from achieving the reliability required to become the backbone of developing economies - or a source of trustworthy information for anybody.

Genetically modified crops (GMOs) and

do-it-yourself (DIY) biotech became backyard and garage activities,

producing important advances. In 2017, a network of renegade African

scientists who had returned to their home countries after working in Western

multinationals unveiled the first of a range of new GMOs that boosted

agricultural productivity on the continent.

The very rich still had the financial means to protect themselves; gated communities sprung up from New York to Lagos, providing safe havens surrounded by slums. In 2025, it was de rigueur to build not a house but a high-walled fortress, guarded by armed personnel.

The wealthy also capitalized on the loose

regulatory environment to experiment with advanced medical treatments and

other under-the-radar activities.

Trust was afforded to those who guaranteed safety and survival - whether it was a warlord, an evangelical preacher, or a mother. In some places, the collapse of state capacity led to a resurgence of feudalism.

In other areas, people managed to create more resilient communities operating as isolated micro versions of formerly large-scale systems. The weakening of national governments also enabled grassroots movements to form and grow, creating rays of hope amid the bleakness.

By 2030, the distinction between

"developed" and "developing" nations no longer seemed particularly descriptive or relevant.

Philanthropic organizations move to support urgent humanitarian efforts at the grassroots level, doing "guerrilla philanthropy" by identifying the "hackers" and innovators who are catalysts of change in local settings.

Yet identifying pro-social entrepreneurs is a

challenge, because verification is difficult amid so much scamming and

deception.

They also pursue a less global approach,

retreating to doing work in their home countries or a few countries that

they know well and perceive as being safe. TECHNOLOGY IN HACK ATTACK

Creative repurposing of existing technologies - for good and bad - is widespread, as counterfeiting and IP theft lower incentives for original innovation. In a world of trade disputes and resource scarcities, much effort focuses on finding replacements for what is no longer available.

Pervasive insecurity means that tools of aggression and

protection - virtual as well as corporeal - are in high demand, as are

technologies that will allow hedonistic escapes from the stresses of life.

But in a world full of deceit and scamming, his skills at discerning fact from fiction and developing quick yet deep local knowledge were highly prized. For three months now he had been working for a development organization, hired to find out what was happening in the "grey" areas in Botswana - a country that was once praised for its good governance but whose laws and institutions had begun to falter in the last few years, with corruption on the rise.

His instructions were simple: focus not on the dysfunctional (which, Trent could see, was everywhere) but rather look through the chaos to see what was actually working. Find local innovations and practices that were smart and good and might be adopted or implemented elsewhere.

"Guerrilla philanthropy" was what they called

it, a turn of phrase that he liked quite a bit.

At the Gaborone airport, it took Trent six hours to clear customs and immigration. The airport was bereft of personnel, and those on duty took their time scrutinizing and re-scrutinizing his visa. Botswana had none of the high-tech biometric scanning checkpoints - technology that could literally see right through you - that most developed nations had in abundance in their airports, along their borders, and in government buildings.

Once out of the airport Trent was shocked by how

many guns he saw - not just slung on the shoulders of police, but carried by

regular people. He even saw a mother with a baby in one arm and an AK-47 in

the other. This wasn't the Botswana he remembered way back when he was

stationed here 20 years ago as an embassy employee.

One of his informants had told him about a group of smart youngsters who had set up their own biotechnology lab on the banks of the Chobe River, which ran along the forest's northern boundary. He'd been outfitted with ample funds for grant-making, not the forest bribes he had heard so much about; regardless of what was taking place in the world around him, he was under strict orders to behave ethically.

Trent was also careful to cover his tracks to avoid being kidnapped by international crime syndicates - including the Russian mafia and the Chinese triads - that had become very active and influential in Botswana. But he'd made it through, finally, to the lab, which he later learned was under the protection of the local gun lord.

As expected, counterfeit vaccines were being manufactured. But so were GMO seeds. And synthetic proteins.

And a host of other innovations that the people who hired him would love to know about.

Vigorous attempts to jumpstart markets and economies didn't work, or at least not fast enough to reverse the steady downward pull. The combined private and public debt burden hanging over the developed world continued to depress economic activity, both there and in developing countries with economies dependent on exporting to (formerly) rich markets.

Without the ability to boost economic activity,

many countries saw their debts deepen and civil unrest and crime rates

climb. The United States, too, lost much of its presence and credibility on

the international stage due to deepening debt, debilitated markets, and a

distracted government. This, in turn, led to the fracturing or decoupling of

many international collaborations started by or reliant on the U.S.'s

continued strength.

Depressed economic activity, combined with the ecological consequences of China's rapid growth, started to take their toll, causing the shaky balance that had held since 1989 to finally break down.

With their focus trained on managing the serious political and economic instability at home, the Chinese sharply curtailed their investments in Africa and other parts of the developing world. Indeed, nearly all foreign investment in Africa - as well as formal, institutional flows of aid and other support for the poorest countries - was cut back except in the gravest humanitarian emergencies.

Overall, economic stability felt so shaky that

the occurrence of a sudden climate shock or other disaster would likely send

the world into a tailspin. Luckily, those big shocks didn't occur, though

there was a lingering concern that they could in the future.

Great numbers of immigrants who had resettled in the developed world suddenly found that the economic opportunities that had drawn them were now paltry at best. By 2018, London had been drained of immigrants, as they headed back to their home countries, taking their education and skills with them.

Reverse migration left holes in the communities of departure - both socially and literally - as stores formerly owned by immigrants stood empty. And their homelands needed them.

Across the developing world and especially in Africa, economic survival was now firmly in local hands. With little help or aid coming through "official" and organized channels - and in the absence of strong trade and foreign currency earnings - most people and communities had no choice but to help themselves and, increasingly, one another.

Yet "survival" and "success" varied greatly by location - not just by country, but by city and by community.

Communities inside failed states suffered the

most, their poor growing still poorer. In many places, the failures of

political leadership and the stresses of economic weakness and social

conflict stifled the ability of people to rise above their dire

circumstances.

Communications and interactions that formerly served to bridge one family or one village or one student with their counterparts in other places - from emailing to phone calls to web postings - became less reliable. Internet access had not progressed far beyond its 2010 status, in part because the investment dollars needed to build out the necessary infrastructure simply weren't there.

When cellphone towers or fiber optic cables

broke down, repairs were often delayed by months or even years. As a result,

only people in certain geographies had access to the latest communication

and Internet gadgets, while others became more isolated for lack of such

connections.

Government capacity improved in more advanced parts of the developing world where economies had already begun to generate a self-sustaining dynamic before the 2008-2010 crisis, such as Indonesia, Rwanda, Turkey, and Vietnam. Areas with good access to natural resources, diverse skill sets, and a stronger set of overlapping institutions did far better than others; so did cities and communities where large numbers of "returnees" helped drive change and improvement.

Most innovation in these better-off places involved modifying existing devices and technologies to be more adaptive to a specific context.

But people also found or invented new ways - technological and non-technological - to improve their capacity to survive and, in some cases, to raise their overall living standards. In Accra, a returning Ghanaian MIT professor, working with resettled pharma researchers, helped invent a cheap edible vaccine against tuberculosis that dramatically reduced childhood mortality across the continent.

In Nairobi, returnees launched a local "vocational education for all" project that proved wildly successful and was soon replicated in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

"THE SPREADING OF IDEAS DEPENDS ON ACCESS TO COMMUNICATION, PEER GROUPS, AND COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE. EVEN IF SOMEONE HAS BLUEPRINTS TO MAKE SOMETHING, THEY MAY NOT HAVE THE MATERIALS OR KNOW-HOW. IN A WORLD SUCH AS THIS,

HOW DO YOU CREATE AN

ECOSYSTEM OF RESEARCH AMONG THESE COMMUNITIES?" Program Director for the Innovations in International Health initiative (IIH), MIT

Makeshift, "good enough" technology solutions - addressing everything from water purification and harnessing energy to improved crop yield and disease control - emerged to fill the gaps.

Communities grew tighter. Micro-manufacturing, communal gardens, and patchwork energy grids were created at the local level for local purposes.

Many communities took on the aura of co-ops, some even

launching currencies designed to boost local trade and bring communities

closer together. Nowhere was this more true than in India, where localized

experiments proliferated, and succeeded or failed, with little connection to

or impact on other parts of the country - or the world.

For those looking, it was difficult to find or

access creative solutions. Scaling was further inhibited by the lack of

compatible technology standards, making innovations difficult to replicate.

Apps developed in rural China simply didn't work in urban India.

But the development of

tangible devices, products, and innovations continued to lag in places where

local manufacturing skills and capacities had not yet scaled. More complex

engineering solutions proved even more difficult to develop and diffuse.

Yet without major progress in global economic integration and collaboration, many worried that good ideas would stay isolated, and survival and success would remain a local - not a global or national - phenomenon.

The meta-goal in this world is to scale up:

Philanthropy requires a keen screening capacity

to identify highly localized solutions, with specialized pockets of

expertise that make partnerships more challenging and transitions between

sectors and issues harder to achieve.

Office space is rented by the day or week, not

the month or year, because more people are in the field - testing,

evaluating, and reporting on myriad pilot projects.

As a result, capacity and knowledge are distributed more widely, allowing many small pockets of do-it-yourself innovation to emerge. Low-tech, "good enough" solutions abound, cobbled together with whatever materials and designs can be found. However, the transfer of cutting-edge technology through foreign direct investment is rare.

Structural deficiencies in the broader

innovation ecosystem - in accessing capital, markets, and a stable Internet

- and in the proliferation of local standards limit wider growth and

development.

She groaned, grabbed the armrests, and held on as the plane dipped sharply before finally settling into a smooth flight path. Lidi hated small planes. But with very few commercial jets crisscrossing Africa these days, she didn't have much choice.

Lidi - an Eritrean by birth - was a social

entrepreneur on a mission that she deemed critical to the future of her home

continent, and enduring these plane flights was an unfortunate but necessary

sacrifice. Working together with a small team of technologists, Lidi's goal

was to help the good ideas and innovations that were emerging across Africa

to spread faster - or, really, spread at all.

She used to worry about how to scale good ideas from continent to continent; these days she'd consider it a great success to extend them 20 miles. And the creative redundancy was shocking! Just last week, in Mali, Lidi had spent time with a farmer whose co-op was developing a drought-resistant cassava.

They were extremely proud of their efforts, and

for good reason. Lidi didn't have the heart to tell them that, while their

work was indeed brilliant, it had already been done. Several times, in

several different places.

She wished there were an easier way to let the innovators in those places know that they might not be inventing, but rather independently reinventing, tools, goods, processes, and practices that were already in use. What Africa lacked wasn't great ideas and talent: both were abundant. The missing piece was finding a way to connect those dots.

And that's why she was back on this rickety plane again and heading to Tunisia.

She and her team were now concentrating on

promoting mesh networks across Africa, so that places lacking Internet

access could share nodes, get connected, and maybe even share and scale

their best innovations.

Three key insights stood out to us as we

developed these scenarios.

In some futures, the primacy of the nation-state as a unit of analysis in development was questioned as both supra- or sub-national structures proved more salient to the achievement of development goals.

In other futures, the nation-state's power strengthened and it became an even more powerful actor both to the benefit and to the detriment of the development process, depending on the quality of governance.

Technologies will affect governance, and

governance in turn will play a major role in determining what technologies

are developed and who those technologies are intended, and able, to benefit.

In some scenarios, philanthropic organizations and other actors in development face a set of obstacles in working with large institutions, but may face a yet-unfolding set of opportunities to work with nontraditional partners - even individuals.

The organization that is able to navigate between these levels and actors may be best positioned to drive success.

DEVELOPMENT-LED INTERVENTIONS ARE OFTEN NOT CAREFUL ENOUGH ABOUT WHAT THE TECHNOLOGY NEEDS IN ORDER TO WORK ON A THREE, FIVE, OR SEVEN YEAR CYCLE. WHAT SCALE IS REQUIRED FOR DEPLOYMENT TO BE SUCCESSFUL? WHAT LEVEL OF EDUCATION IS NEEDED TO BE SUSTAINABLE IN TERMS OF MAINTENANCE?

HOW DO THESE REQUIREMENTS EVOLVE OVER TIME? Professor, University of California-Berkeley School of Information Energy, and Resources Group

The third theme highlights the potential value of scenarios as one critical element of strategy development.

These narratives have served to kick-start the

idea generation process, build the future-oriented mindset of participants,

and provide a guide for ongoing trend monitoring and horizon scanning

activities. They also offer a useful framework that can help in tracking and

making sense of early indicators and milestones that might signal the way in

which the world is actually transforming.

The changing nature of technologies could shape the characteristics of development and the kinds of development aid that are in demand. In a future in which technologies are effectively adopted and adapted by poor people on a broad scale, expectations about the provision of services could fundamentally shift.

Developing a deeper understanding of the ways in which technology can impact development will better prepare everyone for the future, and help all of us drive it in new and positive directions.

These uncertainties were themselves selected from a significantly longer list generated during earlier phases of research and extensive interviewing. The uncertainties fall into three categories: technological, social and environmental, and economic and political.

Each uncertainty is presented along with two polar endpoints, both representing a very different direction in which that uncertainty might develop.

LIST OF PARTICIPANTS

The Rockefeller Foundation and GBN would like to extend special thanks to all of the individuals who contributed their thoughtfulness and expertise throughout the scenario process.

Their enthusiastic participation in interviews,

workshops, and the ongoing iteration of the scenarios made this co-creative

process more stimulating and engaging that it could ever have been

otherwise.

Thank you as well to all Foundation staff who

participated in the scenario creation workshop in December.

|