|

by Andrea Mustain

Staff Writer

February 08, 2012

from

OurAmazingPlanet Website

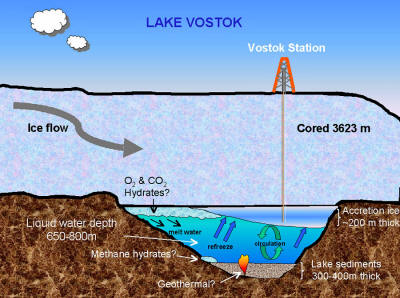

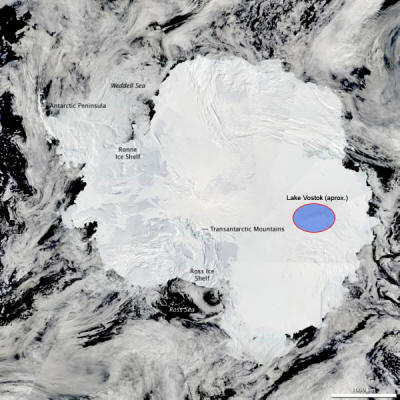

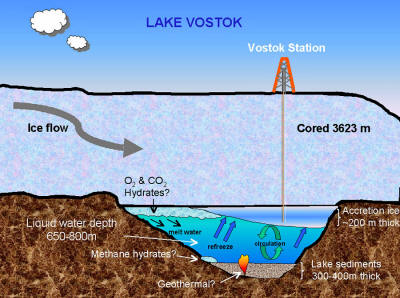

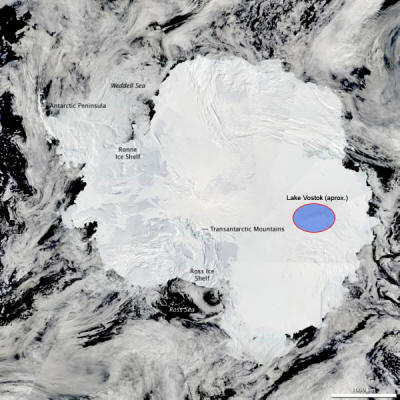

It's official. Russian scientists announced today that they have

reached Antarctica's

Lake Vostok, an ancient, liquid lake the size

of Lake Ontario buried beneath more than 2 miles (~3 kilometers) of

ice for at least 14 million years.

The revelation comes after days of speculation on whether the

years-long effort had finally achieved its goal.

News of the scientific milestone was evidently on hold, as Russian

headquarters waited on some measurements from Vostok Station, the

tiny outpost in the middle of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet where the

Russians

have been drilling toward Lake Vostok since the late 1990s.

In fact, just after 9 a.m. local time (12 a.m. ET), Sergei

Lesenkov, a spokesman for Russia's Arctic and Antarctic Research

Institute, based in St. Petersburg, told OurAmazingPlanet that the

team was still awaiting some final numbers from Antarctica.

"We are waiting for information

which will allow us to confirm this result," Lesenkov said.

He said that it appeared lake water had

shot dozens of meters up into the long borehole, but that an

announcement would likely come on Thursday morning, local time.

Yet it appears the Vostok team came through faster than expected,

and Russia announced to the world that it had reached Lake Vostok

just a few hours later.

The team's ice-coring drill broke through the slushy layer of ice at

the

bottom of the massive ice sheet and

reached fresh, liquid lake water on Feb. 5, at a depth of 12,366

feet (3,769 meters) according to the press release issued today by

the Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute

Scientists suspect that the massive lake could house

cold-loving organisms uniquely

adapted to live in the darkness under the ice.

The lake has been cut

off from the outside world since the ice sheet covered it - as long

as 34 million years ago, or, according to the most modest estimates,

14 million years ago (see

Antarctica's Biggest Mysteries.)

Contamination

concerns

Some scientists have expressed concern over the drill method the

Russians are using at

Lake Vostok.

Their ice-coring drill, which was

originally designed to bore deep into the ice sheet and bring back

long tubes of ice for climate research, uses what is essentially jet

fuel to keep the long borehole from freezing over season after

season, and there are fears that the fuel will contaminate the lake,

or at least the lake water samples retained for research.

The Russians have maintained that, because the Freon, kerosene and

other hydrocarbons in the drill fluid are less dense than water,

that they will be pushed up through the borehole and will never

touch the lake.

Today's press release states that this has indeed

been the case, and that drill fluid was pushed up and away from the

lake itself and into sealed containers.

Drilling began at

Vostok Station in the 1970s, before there was any

inkling that one of the largest lakes on Earth lay beneath the site,

and the drill the Vostok team is using wasn't built to retrieve lake

water.

It can only fetch ice, thus the team

won't be able to actually get their hands on water samples and test

them for life until next season - the water must be left to freeze

in the borehole over the austral winter.

Alive and

well?

Several scientists have said that even if the Russians don't find

evidence of living organisms in the samples they bring back from

Vostok, there's no reason to believe the lake is a dead zone.

"A 'no' answer isn't a clear

negative," said Robin Bell, a geophysicist and professor at

Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, who has

studied Lake Vostok and other buried Antarctic lakes for more

than a decade.

Bell said that life likes to gather on

the edges of environments.

"We like to live on the beach," she said

So it's likely that anything living in the lake might set up house

in the mud at the bottom, or at the edges of the ice.

The Vostok project is sampling only surface layers of the lake, from

one of its shallowest areas, because of the location of the station

itself. When the Soviets built Vostok Station in the mid-20th

century, they happened to choose a spot right over the southern tip

of the lake.

The lake's true scale wasn't officially established until the

mid-1990s, and data now indicate the lake is roughly 155 miles (250

km) long, 50 miles (80 km) wide in places, and more than 1,600 feet

(500 m) deep.

And soon, the Russians are going to have some friendly competition

in the quest to sample ice-covered lakes that have been cut off for

millennia. [Race to the South Pole in Images]

Teams from the United States and the United Kingdom are set to begin

their own drilling projects to long-buried Antarctic lakes, and have

the advantage of state-of-the-art equipment designed specifically

for the task.

Both the British and American teams are using hot-water drills which

can reach their targets in mere days, and have the ability to

retrieve liquid samples from throughout the lakes' depth, including

sediment at the bottom, and the samples can be brought back to the

surface within 24 hours.

The British are poised to

begin drilling to Lake Ellsworth, a lake

in West Antarctica buried beneath 2 miles (3 km) of ice, in autumn

2012, and may be the first team to put Antarctic lake water under a

microscope.

Rumors and

speculation

Today's announcement comes amid a flurry of rumors and exaggerated

reporting surrounding

the Lake Vostok project, which some have

likened to the plot of a science fiction movie.

At least one Russian news outlet reported on Monday that an

anonymous source said the team had reached the lake, then went on to

discuss rumors that Vostok Station, established by the Soviets in

1957, was also the site of

a long-lost Nazi hideout, and that German

submarines brought Hitler's and Eva Braun's remains to Antarctica

for cloning purposes.

Days before that, some American and British news outlets circulated

reports that the scientists working at Vostok Station had lost radio

contact with the outside world and were missing or in danger.

That was never the case.

"I never said that the Russians were

lost, as [other news organizations] indicated," John Priscu, an

American microbiologist and veteran Antarctic researcher who has

been in intermittent contact with St. Petersburg during the

2011-2012 field season, told OurAmazingPlanet in an email.

After more than a decade of work, and at

least two seasons when the team came agonizingly close to reaching

Lake Vostok, today's announcement was a welcome one, and coincides

with Russia's Day of Science, celebrated on Feb. 8.

"This achievement of Russian polar

researchers and engineers has been a wonderful gift," concluded

the press release from the Arctic and Antarctic Research

Institute.

When asked if, after so many years, it

was exciting to finally reach Lake Vostok, Lesenkov replied in

restrained fashion.

"Da," he said. "Yes."

It did sound as though he was smiling.

|