|

by Andrew Collins

New Dawn Magazine No. 43

July-August 1997

from

NewDawnMagazine Website

Spanish version

In the recent past the tranquility of the Beqa'a Valley, that runs

north-south between the Lebanon and Ante-Lebanon mountain ranges,

has been regularly shattered by the screeching noise of Israeli jet

fighters.

Their targets are usually the Hizbullah training camps,

mostly for reconnaissance purposes, but occasionally to drop bombs

on the local inhabitants. It is a sign of the times in the troubled

Middle East.

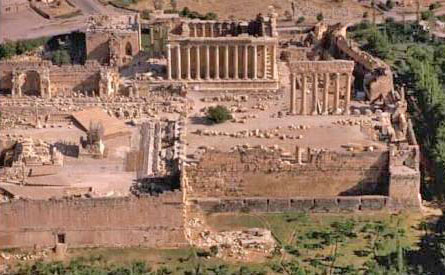

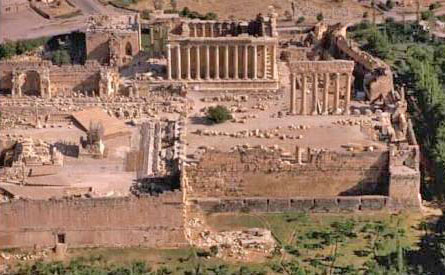

Yet the Beqa'a Valley is also famous for quite another reason.

Elevated above the lazy town of Baalbek is one of architecture's

greatest achievements. I refer to the almighty Temple of Jupiter,

situated besides two smaller temples, one dedicated to Venus, the

goddess of love, and the other dedicated to Bacchus, the god of

fertility and good cheer (although some argue this temple was

dedicated to Mercury, the winged god of communication).

Today these wonders of the classical world remain as impressive

ruins scattered across a wide area, but more remarkable still is the

gigantic stone podiums within which these structures stand. An outer

podium wall, popularly known as the 'Great Platform', is seen by

scholars as contemporary to the Roman temples.

Yet incorporated into

one of its courses are the three largest building blocks ever used

in a man-made structure. Each one weighs an estimated 1000 tonnes a

piece.(1)

They sit side-by-side on the fifth level of a truly

cyclopean wall located beyond the western limits of the Temple of

Jupiter.

Even more extraordinary is the fact that in a limestone quarry about

one quarter of a mile away from the Baalbek complex is an even

larger building block. Known as Hajar el Gouble, the Stone of the

South, or the Hajar el Hibla, the Stone of the Pregnant Woman, it

weighs an estimated 1200 tonnes.(2)

It lays at a raised angle - the

lowest part of its base still attached to the living rock - cut and

ready to be broken free and transported to its presumed destination

next to

the Trilithon, the name given to the three great stones in

ancient times.

The enigma is this - although the high-tech, computer programmed jet

fighters that scream through the Beqa'a Valley possess laser-guided

missiles that can precision bomb to within three feet of their

designated target, there is not a crane today that can even think of

lifting a 1000-tonne weight, never mind a 1200-tonne weight like the

stone block left in the quarry.

Confounding the mystery even further

is how the builders of the Trilithon managed to position these

stones side by side with such precision that, according to some

commentators not even a needle can be inserted between them.(3)

So who were the supermen behind this breath-taking project? Surely

the world is aware of their origins and history. Who were these

people?

Unfortunately, however, nobody knows their names. Nowhere in extant

Roman records does it mention anything at all about the architects

and engineers involved in the construction of the Great Platform.

No

contemporary Roman historian or scholar commentates on how it was

constructed, and there are no tales that preserve the means by which

the Roman builders achieved such marvelous feats of engineering.

Why? Why the silence?

Surely someone, somewhere, must know what happened.

And herein the problems begin, for the local inhabitants of the

Beqa'a Valley - who consist in the main of Arab Muslims, Maronite

Christians and Orthodox Christians - do preserve legends about the

origins of the Great Platform, but they do not involve the Romans.

They say that Baalbek's first city was built before the Great Flood

by Cain, the son of Adam, whom God banished to the 'land of Nod'

that lay 'east of Eden' for murdering his good brother Abel, and he

called it after his son Enoch.(4) The citadel, they say, fell into

ruins at the time of the deluge and was much later re-built by a

race of giants under the command of Nimrod, the 'mighty hunter' and

'king of Shinar' of the Book of Genesis.(5)

So,

-

Who do we believe - the academics who are of the opinion that

the

Great Platform was constructed by the Romans, or the local folktales

which ascribe Baalbek's cyclopean masonry to a much earlier age?

-

And

if we are to accept the latter explanation, then who exactly were

these 'giants', gigantes or Titans of Greek tradition?

-

Furthermore,

why accredit Cain, Adam's outcast son, as the builder of Baalbek's

first city?

In an attempt to answer some of these questions it will be necessary

to review the known history of Baalbek and to examine more closely

the stones of the Trilithon in relationship to the rest of the ruins

we see today.

It will also be necessary to look at the mythologies,

not only of the earliest peoples of Lebanon, but also the Hellenic

Greeks.

Only by doing this will a much clearer picture begin to

emerge.

Heliopolis of the East

Scholars suggest that Baalbek started its life as a convenient

trading post between the Lebanese coast and Damascus.

What seems

equally as likely, however, is that - situated close at the highest

point in the Beqa'a, and set between the headwaters of Lebanon's two

greatest rivers, the Orontes and Leontes - this elevated site became

an important religious centre at a very early date indeed.

Excavations in the vicinity of the Great Court of the Temple of

Jupiter have revealed the existence of a tell, or occupational mound,

dating back to the Early Bronze age (c.2900-2300 BC).(6)

By the late second millennium BC a raised court, entered through a

gateway with twin towers, had been constructed around a vertical

shaft that dropped down some fifty yards to a natural crevice in

which 'a small rock cut altar' was used for sacrificial rites.(7)

In the hills around the temple complex are literally hundreds of

rock-cut tombs which, although plundered long ago, are thought to

date to the time of the Phoenicians,(8) the great sea-faring nation

of Semitic origin who inhabited Lebanon from around 2500 BC onwards

and were known in the Bible as the Canaanites, the people of Canaan.

They established major sea-ports in Lebanon, northern Palestine and

Syria, as well as trading posts across the Mediterranean and the

eastern Atlantic seaboard, right through till classical times.

Indeed, it is believed that Phoenicia's mythical history heavily

influenced the development of Greek myth and legend.

Following the death of Alexander in 323 BC, Phoenicia was ruled

successively by the Ptolemaic kings of Egypt and the Seleucid kings

of Syria until the arrival of the Romans under a general named

Pompey in 63 BC.

The first-century AD Jewish historian Josephus

tells of Alexander's march through the Beqa'a on his way to

Damascus, during which he encountered the cities of 'Heliopolis and Chalcis'.(9) Chalcis, modern Majdel Anjar, was then the political centre of the

Beqa'a, while Baalbek was its principal religious centre.

Heliopolis was the name given to Baalbek under the Ptolemies of

Egypt sometime between 323 and 198 BC. Meaning 'city of the sun', it

expressed the importance this religious centre held to the Egyptians,

particularly since a place of immense antiquity bearing this same

name already existed in Lower Egypt.

Following a brief period in which Mark Anthony handed Lebanon and

Syria back to Queen Cleopatra, the last Ptolemaic queen of Egypt,

Lebanon became a Roman colony around 27 BC, and it was during this

phase in its history that construction began on the Baalbek temples.(10)

The principal deity they chose to preside over Baalbek was Jupiter,

the sky god. He was arguably the most important deity of the Romans,

taking over the role of Zeus in the Greek pantheon. Jupiter was

probably chosen to replace the much earlier worship of the Canaanite

god Baal (meaning 'lord') who had many characteristics in common

with the Greek Zeus.

It is, of course, from Baal that

Baalbek

derives its name, which means, simply, 'town of Baal'. Yet when, and

how, this god of corn, rain, tempest and thunder, was worshipped

here is not known, even though legend asserts that Baalbek was the

alleged birth-place of Baal. (11)

In the Bible Baalbek appears under

the name Baalath,(12) a town re-fortified by Israel's King Solomon,

c. 970 BC (1 Kings 9:18 & 2 Chr. 8:6), confirming both its sanctity

to Baal at this early date and its apparent strategic importance on

the road to Damascus.

Some scholars have suggested that Baal (Assyrian Hadad) was only one

of a triad of Phoenician deities that were once venerated at this

site - the others being his son Aliyan, who presided over well-springs

and fecundity, and his daughter Anat (Assyrian Atargatis), who was

Aliyan's devoted lover.

These three correspond very well with the

Roman triad of Jupiter, Mercury and Venus, whose veneration is

almost certainly preserved in the dedication of the three temples at Baalbek. Many Roman emperors were of Syrian extraction, so it would

not have been unusual for them to have promoted the worship of the

country's indigenous deities under their adopted Roman names.(13)

Whatever the nature of the pre-Roman worship at Baalbek, its

veneration of Baal created a hybrid form of the god Jupiter,

generally referred to as Jupiter Heliopolitan.

One surviving statue

of him in bronze shows the beardless god sporting a huge calathos

head-dress, a symbol of divinity, as well as a bull, a symbol of

Baal, on either side of him.(14)

The Temple of Jupiter

When the Romans began construction of the gigantic Temple of Jupiter

- the largest of its kind in the classical world - during the reign

of Emperor Augustus in the late first century BC, they

utilized an

existing podium made up of huge walls of enormous stone blocks.(15)

This much is known. Academics suggest that this inner podium, or

rectangular stone platform filled level with earth, was an

unfinished component of an open-air temple constructed by the

Seleucid priesthoods on the existing Bronze Age tell sometime

between 198 and 63 BC.(16)

Baalbek's great sanctity was well-known

even before the building of the temple, for it is said to have

possessed a renowned oracle which, according to a Latin grammarian

and author named Macrobius (fl. AD 420), expressed itself through

the movement of a great statue located in the courtyard.

It was

attended by 'dignitaries' with shaven heads who had previously

undergone long periods of ritual abstinence.(17)

As the temple complex expanded throughout Roman times, the existing

foundations extended southwards, beyond the inner podium, to where

the Temple of Bacchus (or Mercury) was eventually constructed in the

middle of the second century BC.

It also extended north-eastwards to

where a great court, an observation tower, an enclosed hexagonal

court and a raised, open-air altar were incorporated into the

overall design. To the south, outside the Great Court, rose the much

smaller Temple of Venus as well as the lesser known Temple of the

Muses.

According to Professor H. Kalayan, whose extensive surveying

program of the Baalbek complex was published in 1969, the Temple

of Jupiter and its east facing courtyard were planned simultaneously

as one overall design.(18)

Yet in the age of Augustus this should

have meant that the temple be placed at one end of a courtyard that

surrounded it on all sides; it was the style of the day. This,

however, is not what happened at Baalbek, for its courtyard ceased

in line with the temple facade.

This Professor Kalayan saw as a

deliberate change of policy, even though 'foundations' for an

extension to this courtyard were already in place on the north side

of the temple.(19)

The Trilithon

Did the Roman architects of Baalbek chop and change their minds so

easily?

Their next move would appear to suggest as much, for they

decided that, instead of extending the courtyard, they would

continue the existing pre-Roman temple podium behind the western end

of the Temple of Jupiter. This mammoth building project apparently

necessitated the cutting, transporting and positioning of the three

1000-tonne limestone blocks making up the Trilithon.

Their sizes

vary between sixty-three and sixty-five feet in length, while each

one shares the same height of fourteen feet six inches and a depth

of twelve feet.(20)

Seeing them strikes a sense of awe unimaginable

to the senses, for as a former Curator of Antiquities at Baalbek,

Michel M. Alouf, aptly put it:

'No description will give an exact

idea of the bewildering and stupefying effect of these tremendous

blocks on the spectator'.(21)

The course beneath the Trilithon is almost as bewildering.

It

consists of six mammoth stones thirty to thirty three feet in

length, fourteen feet in height and ten feet in depth,(22) each an

estimated 450 tonnes in weight. This lower course continues on both

the northern and southern faces of the podium wall, with nine

similarly sized blocks incorporated into either side.

Below these

are at least three further courses of somewhat smaller blocks of

mostly irregular widths which were apparently exposed when the Arabs

attempted to incorporate the outer podium wall into their

fortifications.(23)

Indeed, above and around

the Trilithon is the

remains of an Arab wall that contrasts markedly from the much

greater sized cyclopean stones.

There is no good reason why the Roman architects should have needed

to use such huge blocks, totally unprecedented in engineering

projects of the classical age. Further confounding the picture is

that the outer podium wall was left 'incomplete'.

Furthermore, the

even larger 1200-tonne cut and dressed Stone of the Pregnant Woman

lying in the nearby quarry - which measures an incredible sixty-nine

feet by sixteen feet by thirteen feet ten inches(24)

- would imply

that something went wrong, forcing the engineers to abandon

completion of the Great Platform.

Why?

Scholars can only gloss over the necessity to use such ridiculously

large sized blocks.

Baalbek scholar Friedrich Ragette, in his 1980

work entitled, simply, Baalbek, suggests that such huge stones were

used because 'according to Phoenician tradition, (podiums) had to

consist of no more than three layers of stone' and since this one

was to be twelve meters high, it meant the use of enormous building

blocks.(25)

It is a

solution that rings hollow in my ears. He further adds that stones

of this size and proportion were also employed 'in the interest of

appearance'.(26)

In the interest of appearance? But they don't even look right - the

Trilithon looks alien in comparison to the rest of the wall.

Ragette points out that the sheer awe inspired by the Trilithon

ensured that Baalbek was remembered by later generations, not for

the grandeur of its magnificent temples, but for its three great

stones which ignorant folk began to believe were built by superhuman

giants of some bygone age.(27)

Was this the real explanation why giants were accredited with the

construction of Baalbek - because naive inhabitants and travelers

could not accept that the Romans had the power to achieve such grand

feats of engineering?

There is no answer to this question until all the evidence has been

presented in respect to the construction of the Great Platform, and

it is in this area that we find some very contradictory evidence

indeed. For example, when the unfinished upper course of the Great

Platform was cleared of loose blocks and rubble, excavators found

carved into its horizontal surface a drawing of the pediment (a

triangular, gable-like piece of architecture present in the Temple

of Jupiter).

So exact was this design that it seemed certain the

architects and masons had positioned their blocks using this scale

plan.(28) This meant that

the Great Platform must have existed

before the construction of the temple.

On the other hand, a stone column drum originally intended for the

Temple of Jupiter was apparently found among the foundation rubble

placed beneath the podium wall.(29) This is convincing evidence to

show that the Great Platform was constructed at the same time,

perhaps even later, than the temple.

So the Great Platform turns out to be Roman after all, or does it?

It could be argued that the column drum was used as ballast to

strengthen the foundations of the much earlier podium wall, and

until further knowledge of exactly where this cylindrical block was

found then the matter cannot be resolved either way.

The Big Debate

The next problem is whether or not the Romans possessed the

engineering capability to cut, transport and position 1000-tonne

blocks of this nature.

Since the Stone of the Pregnant Woman was

presumably intended to extend the Trilithon, it must be assumed that

the main three stones came from the same quarry, which lies about

one quarter of a mile from the site. Another similar stone quarry

lies some two miles away, but there is no obvious evidence that the Trilithon stones came from there.

Having established these facts, we must decide on how the Roman

engineers managed to cut and free 1000-tonne stones from the

bed-rock and then move them on a steady incline for a distance of

several hundred yards.

Ragette suggests that the Trilithon stones were first cut from the

bed-rock, using 'metal picks' and 'some sort of quarrying machine'

that left concentric circular blows up to four meters in radius on

some blocks (surely an enigma in itself).(30)

They were then

transported to the site by placing them on sleighs that rested on

cylindrical wooden rollers. As he points out, similar methods of

transportation were successfully employed in Egypt and Mesopotamia,

as is witnessed by various stone reliefs.(31)

This is correct, for

there do exist carved images showing the movement of either statues

or stone blocks by means of large pulley crews. These are aided by

groups of helpers who either mark-time or pick up wooden rollers

from the rear end of the train and then place them in the path of

the slow-moving procession.

Two major observations can be made in respect to this solution.

-

Firstly, this process requires a flat even surface, which if not

present would necessitate the construction of a stone causeway or

ramp from the quarry to the point of final destination (as is

evidenced at Giza in Egypt). Certainly, there is a road that passes

the quarry on the way to the village, but there is still much rugged

terrain between here and the final position of the blocks.

-

Secondly,

the reliefs depicting the movement of large weights in Egypt and

Assyria show individual pieces that are an estimated 100 tonnes in

weight - one tenth the size of the Trilithon stones. I feel sure

that the movement of 1000-tonne blocks would create insurmountable

difficulties for the suggested pulley and roller system. One French

scholar calculated that to move a 1000-tonne block, no less than

40,000 men would have been required, making logistics virtually

inconceivable on the tiny track up to the village.(32)

Practically Impossible

The next problem is how the Romans might have maneuvered the giant

blocks into position.

Ragette suggests the 'bury and re-excavate'

method,(33) where ramps of compacted earth would be constructed on a

slight incline up to the top of the wall - which before the Trilithon was added stood at an estimated twenty-five feet high.

The

blocks would then be pulled upwards by pulley gangs on the other

side until they reached the required height; a similar method is

thought to have been employed to erect the horizontal trilithon

stones at Stonehenge, for instance.

Playing devil's advocate here, I

would ask:

-

How did the pulley gangs manage to bring together these

stones so exactly and how were they able to achieve such precision

movement when the land beyond the podium slopes gently downwards?

Only by creating a raised ramp on the hill-slope itself, and then

placing the pulley gangs on the other side of the wall could an

operation of this kind even be attempted.

-

And how were the stone blocks lifted from the rollers to allow final

positioning? Ragette proposes the use of scaffoldings, ramps and

windlasses (ie. capstans) like those employed by the Renaissance

architect Domenico Fontana to erect a 327-tonne Egyptian obelisk in

front of St Peter's Basilica in Rome. To achieve this amount of

lift, Fontana used an incredible 40 windlasses, which necessitated a

combined force of 800 men and 140 horses.

Based on an estimated weight of 800 tonnes per stone(34) (even

though he cites each one as 1000-tonnes a piece earlier in the same

book(35)), Ragette proposes that, with a five-tonne

lifting capacity per drilled Lewis hole, each block would have

required 160 attachments to the upper surface.

He goes on:

'Four each could be hooked to a

pulley of 20 tons capacity which in the case of six rolls needed

an operating power of about 3« tons. The task therefore

consisted of the simultaneous handling of forty windlasses of 3«

tons each. The pulleys were most likely attached to timber

frames bridging across the stone.'(36)

Such ideas are pure speculation.

No evidence of any such

transportation has ever come to light at Baalbek, and the surface of

the Trilithon has not revealed any tell-tale signs of drilled Lewis

holes.

Admittedly, the Stone of the Pregnant Woman remaining in the

quarry does contain a seemingly random series of round holes in its

upper surface, yet their precise purpose remains a mystery.

As evidence that the Romans possessed the knowledge to lift and

transport extremely heavy weights, Ragette cites the fact that

between AD 60 and 70, i.e. the proposed time-frame of construction of

the Jupiter temple, a man named Heron of Alexandria compiled an

important work outlining this very practice, including the use of

levers to raise up and position large stone blocks.(37)

Curiously,

the only surviving example of this treatise is an Arabic translation

made by a native of Baalbek named Costa ibn Luka in around 860

AD.(38)

Did it suggest that knowledge of this engineering manual had

been preserved in the town since Roman times, being passed on from

generation to generation until it finally reached the hands of Costa ibn Luka?

Of course it is possible, but whether or not it was of any

practical use when it came to the construction of the Trilithon is

quite another matter.

The Archaeologists' View

No one can rightly say whether or not the Romans really did have the

knowledge and expertise to construct the Great Platform; certainly

some of the Temple of Jupiter's tall columns of Aswan granite, at

sixty-five feet in height, are among the largest in the world.

And

even if we presume that they did have the ability, then this cannot

definitively date the various building phases at Baalbek. For the

moment, it seemed more important to establish whether there existed

any independent evidence to suggest that the Great Platform might

not have been built by the Romans.

Over the past thirty or so years a number of ancient mysteries

writers have seen fit to associate the Great Platform with a much

earlier era of mankind, simply because of the sheer uniqueness of

the Trilithon. They have suggested that the Romans built upon an

existing structure of immense antiquity. Unfortunately, however,

their personal observations cannot be taken as independent evidence

of the Great Platform's pre-Roman origin.

There is, however, tantalizing evidence to show that some of the

earliest archaeologists and European travellers to visit Baalbek

came away believing that the Great Platform was much older than the

nearby Roman temples.

For instance, the French scholar, Louis Flicien de Saulcy, stayed at

Baalbek from 16 to 18 March 1851 and

became convinced that the podium walls were the 'remains of a

pre-Roman temple'.(39)

Far more significant, however, were the observations of respected

French archaeologist Ernest Renan, who was allowed archaeological

exploration of the site by the French army during the mid nineteenth

century.(40) It is said that when he arrived there it was to satisfy

his own conviction that no pre-Roman remains existed on the

site.(41)

Yet following an

in-depth study of the ruins, Renan came to

the conclusion that the stones of the Trilithon were very possibly

'of Phoenician origin',(42) in other words they were a great deal

older that the Roman temple complex. His reasoning for this

assertion was that, in the words of Ragette, he saw 'no inherent

relation between the Roman temple and this work'.(43)

Archaeologists who have followed in Renan's footsteps have closed up

this gap of uncertainty, firmly asserting that the outer podium wall

was constructed at the same time as the Temple of Jupiter, despite

the fact that inner podium wall is seen as a pre-Roman construction.

Yet the openness of individuals such as de Saulcy and Renan gives us

reason to doubt the assertions of their modern-day equivalents.

A similar situation prevails in Egyptology, where in the late

nineteenth, early twentieth centuries megalithic structures such the

Valley Temple at Giza and the Osireion at Abydos were initially

ascribed very early dates of construction by archaeologists before

later being cited as contemporary to more modern structures placed

in their general proximity.

As has now become clear from recent

research into

the age of the Great Sphinx, there was every reason to

have ascribed these cyclopean structures much earlier dates of

construction.

So what was it that so convinced early archaeologists and travelers

that the Trilithon was much older than the rest of the temple

complex?

The evidence is self apparent and runs as follows:

-

One has only to look at the positioning of the Trilithon and the

various courses of large stone blocks immediately beneath it to

realize that they bear very little relationship to the rest of the

Temple of Jupiter. Moreover, the visible courses of smaller blocks

above and to the right of the Trilithon are markedly different in

shape and appearance to the smaller, more regular sized courses in

the rest of the obviously Roman structure.

-

The limestone courses that make up the outer podium base - which,

of course, includes the Trilithon - are heavily pitted by wind and

sand erosion, while the rest of the Temple of Jupiter still

possesses comparatively smooth surfaces. The same type of wind and

sand erosion can be seen on the huge limestone blocks used in many

of the megalithic temple complexes around the northern Mediterranean

coast, as well as the cyclopean walls of Mycenean Greece. Since all

these structures are between 3000 and 6000 years of age, it could be

argued that the lower courses of the outer podium wall at Baalbek

antedate the Roman temple complex by at least a thousand years.

-

Other classical temple complexes have been built upon much

earlier megalithic structures. This includes the Acropolis in Athens

(erected 447-406 BC), where archaeologists have unearthed cyclopean

walls dating to the Mycenean or Late Bronze Age period (1600-1100

BC). Similar huge stone walls appear at Delphi, Tiryns and

Mycenae.

-

The Phoenicians are known to have employed the use of cyclopean

masonry in the construction of their citadels. For instance, an

early twentieth-century drawing of the last-remaining prehistoric

wall at Aradus, an ancient city on the Syrian coast, shows the use

of cyclopean blocks estimated to have been between thirty and forty

tonnes a piece.

These are important points in favor of the Great Platform, as in

the case of the inner podium, being of much greater antiquity than

the Roman, or even the Ptolemaic, temple complex.

Yet if we were to

accept this possibility, then we must also ask ourselves: who

constructed it, and why?

Part 2

The First Phoenicians

Only one account of Lebanon's mythical origins has been left to

posterity, and this is the work of Sanchoniatho, a Phoenician

historian born either in Berytus (Beirut) or Tyre on the Lebanese

coast just before the Trojan war, c. 1200 BC.

He wrote in his native

language, taking his information mostly from city archives and

temple records. In all he compiled nine books, which were translated

into Greek by Philo, a native of Byblos on the Levant coast, who

lived during the reign of the emperor Hadrian (reigned AD 117-138).

Fragments of his translation were fortunately preserved by an early

Christian writer named Eusebius (AD 264-340).(44)

Some scholars look

upon Sanchoniatho's writings as spurious, but others see them as

preserving archaic myths of the earliest Phoenicians.

In his long discourse on the cosmogony of the world and the history

of the earliest inhabitants of Lebanon, Sanchoniatho cites Byblos as

Lebanon's first city.(45)

It was founded, he says, by the

god Cronus

(or Saturn), the son of Ouranus (Uranus or Coelus, who gave his name

to Coele-Syria, ie. Syria), and grandson of Elioun (Canaanite

El)

and his wife Beruth (who gave her name to the city-port of Berytus

or Beirut).

Sanchoniatho goes on to say that the demi-gods of Byblos possessed

'light and other more complete ships', implying they were a

sea-faring nation.

He also states that chief among these people was Taautus,

'who invented the writing of the

first letters: him the Egyptians called Thoor, the Alexandrians

Thoyth, and the Greeks Hermes.'(46)

He was Cronus' 'secretary', from whom the god gained

advice and assistance on all matters.

A confusing sequence of events are described for this period, during

which time Cronus is constantly at war with his father Ouranus.

There are also marriages, inter-marriages and incestuous

relationships which produce a multitude of characters, many of whom

act as symbols for the expansion of this mythical culture around the

Levant and into Asia Minor (modern Turkey).

For instance, there is

Sidon, the daughter of Pontus, who 'by the excellence of her singing

first invented the hymns of odes or praises'.(47)

Like Byblos, Sidon

was a Phoenician city-port on the Lebanese coast, while Pontus was

an ancient kingdom situated on the Black Sea in what is today

north-eastern Turkey.

Finally, it is said that having visited 'the country of the south'

Cronus

'gave all Egypt to the god Taautus, that it might be his

kingdom',(48) implying that he was its founder.

Sanchoniatho tells us that knowledge of the age of the demi-gods of

Byblos was handed down for generation after generation until it was

given into the safe-keeping of 'the son of Thabion... the first

Hierophant of all among the Phoenicians'.(49)

He in turn delivered

them up to the priests and prophets until they came into the

possession of one Isiris, 'the inventor of the three letters, the

brother of Chna who is called the first Phoenician.'(50)

There is much more in Sanchoniatho's mythical history, but the basic

message is that a high culture with sea-faring capabilities

established itself at Byblos before gradually expanding into other

parts of the eastern Mediterranean.

More curious is his assertion

that the god Taautus, the Phoenician form of the Egyptian Thoth or

Tehuti and the Greek Hermes, was some kind of founder of the

Egyptian Pharaonic culture which began c. 3100 BC.

Was Sanchoniatho's work simply fable, based on the Phoenicians' own

maritime achievements, or might it contain clues concerning an

actual high culture that existed in the Levant during prehistoric

times?

Journey to Byblos

Certainly, the implied link between Egypt and Byblos is real enough.

In the legend of Osiris and Isis, as recorded by the Greek

biographer Plutarch (AD 50-120), the evil god Set tricks Osiris into

a wooden coffin which is sealed before being set adrift on the sea.

It is carried by the waves until it finally reaches Byblos, where it

comes to rest in the midst of a tamarisk bush, which immediately

grows to become a magnificent tree of great size. Inside it the

coffin containing the body of Osiris remains encased.

The king of

that country, on seeing the great tree, has it cut down and made

into 'a pillar for the roof of his house'.(51) Isis learns of what

has happened to her husband and is able to attain entry into the

palace as a handmaiden to one of the king's sons. Each night she

takes on the form of a swallow to fly around the pillar.

After a

fashion she convinces the queen to give her the pillar, which is

then opened to reveal the body of Osiris.(52)

Byblos is the clear name used in

Plutarch's account, but for some

reason noted Egyptologists such as Sir E.A. Wallis-Budge have seen

fit to identify this place-name with a location named Byblos in the

Nile Delta, even though Plutarch himself adds that wood from the

pillar, which was afterwards restored by Isis and given to the

queen,

'is, to this day, preserved in the temple of Isis, and

worshipped by the people of Byblos'.(53)

In my opinion, setting this

story in the Nile Delta makes no sense whatever, especially as the

coffin was said to have been 'carried (to Byblos) by the sea'.(54)

Lucian, the celebrated Greek writer (AD 120-200), spoke of the

Isis-Osiris legend and connected it specifically with Byblos in

Lebanon, adding that 'I will tell you why this story seems credible.

Every year a human head floats from Egypt to Byblos'. This

'head'

apparently took seven days to reach its destination. It never went

off course and came via a 'direct route' to Byblos.

Lucian claimed

that this once yearly event actually happened when he himself was in Byblos, for as he records,

'I myself saw the head in this city'.(55)

What exactly Lucian witnessed, and what was really behind this head

tradition is utterly unfathomable, particularly as Lucian states

that the head he saw was made of 'Egyptian papyrus'.(56)

In

Christian times a St Kyrillos also apparently witnessed the event,

but said that 'what was borne towards him by the wind looked like a

small boat'.(57) All that can be said with any certainty is that

this peculiar tradition appeared to preserve some kind age-old

twinning between Egypt and Byblos, perhaps during the mythical age

of the gods,

the Zep Tepi, or 'First Time.'

As has been ably

demonstrated by recent works from Hancock, Bauval et al, this

believed mythical age, when gods ruled the earth, appears to have

been an actual stage of human development pre-dating Pharaonic Egypt

by many thousands of years.(58)

Yet how might this new-found knowledge of the relationship between

Egypt and Byblos relate to Baalbek?

Firstly there appears to have been a strong link between Isis-Osiris

legend and the mountains north-west of Baalbek.

It was said that

Isis took 'refuge' (presumably at the point in the story when the

king and queen of Byblos discover she is daily incinerating their

child on a blazing fire!) in the lake of Apheca, the ancient name

for Lake Yammouneh some 32km distance from Baalbek, 'and thus lived

in Lebanon', or so recorded the Baalbek archaeologist and historian

Michel M. Alouf.) (59)

The more obvious answer, however, appears to be an apparent twinning

that existed between Heliopolis in Egypt and Heliopolis in Lebanon.

The fifth-century Latin grammarian Macrobius wrote specifically on

this subject in his curious work entitled Saturnalia. He stated that

a 'statue' was carried ritually from Heliopolis in Egypt to its

Lebanese name-sake by Egyptian priests. He adds that after its

arrival it was worshipped with Assyrian rather than Egyptian rites.(60)

Some authors have suggested that this statue was that of the

Egyptian sun-god, presumably Re, while others say it was a

representation of Osiris.(61) In addition to this statue story,

there was also a strong tradition, recounted by Macrobius and

others, that the Egyptian priests actually erected a temple at

Baalbek dedicated to the worship of the sun.(62)

If so, then,

-

What

special place did this ancient location, sacred to Baal, hold to the Heliopolitan priesthood in Egypt?

-

Might this transmission of

religious ideals from Egypt to Baalbek have been connected in some

way to the once yearly arrival of an Egyptian 'head' at Byblos, and

to Osiris' fateful journey inside a sealed coffin?

Titans and Elohim

Aside from the suggested link with the Egyptian culture, the

writings of Sanchoniatho throw further light on this apparent

pre-Phoenician culture existing in the Levant during prehistoric

times.

He says that the 'auxiliaries' or 'allies' of Cronus,

presumably in battle, were the 'Eloeim' a misspelling of the term

Elohim, the sons of whom (the bene ha-elohim) were said to have been

a divine race that came unto the Daughters of Man who subsequently

gave birth to giant offspring known as

the Nephilim, or so records

to the Book of Genesis and various uncanonical works of Judaic

origin.(63)

Elsewhere I have put forward the hypothesis that the Sons of the Elohim - who are equated with the

angelic race known as

the Watchers

in the apocryphal

Book of Enoch, as well as in recently translated

Dead Sea literature - were a race of human beings.

Evidence

indicates they established a colony in the mountains of Kurdistan in

south-east Turkey sometime after the cessation of the last Ice Age,

before going on to influence the rise of western civilization.

Their

progeny, the Nephilim, were half-mortal, half-Watcher, and there is

tentative evidence in the writings of Sumer and Akkad to suggest

that the accounts of great battles being fought between mythical

kings and demons dressed as bird-men might well preserve the

distorted memories of actual conflicts between mortal armies and

Nephilim-led tribes.(64)

Might Cronus - who or whatever he represents - have employed the

services of the bene ha-elohim in the wars against his father,

Ouranus? In Greek mythology the Nephilim are equated directly with

the Titans and gigantes, or 'giants', who waged war on the gods of

Olympus and, like Cronus, were the offspring of Ouranus.

In many

ancient writings preserved during the early Christian era, stories

concerning the Nephilim, or gibborim, 'mighty men', of biblical

tradition are confused with the legends surrounding the Titans and gigantes.

All blend together as one, and not perhaps without reason. The

giants and Titans are said to have helped Nimrod, the 'mighty

hunter' construct the fabled Tower of Babel which reached towards

heaven.

On its destruction by God, legends speak of how the giant

races were dispersed across the bible lands.(65)

According to an Arabic manuscript found at Baalbek and quoted by

Alouf in his informative History of Baalbek,

'after the flood, when Nimrod

reigned over Lebanon, he sent giants to rebuild the fortress of

Baalbek, which was so named in honour of Baal, the god of the

Moabites and worshippers of the Sun.'(66)

Local tradition even

asserts that the Tower of Babel was actually located at Baalbek.(67)

The involvement of Nimrod in this legend is almost certainly a

misnomer, born out of the belief that only super-humans of myth and

fable could ever have built such gigantic stature, in the same way

that either named giants or mythical figures, such as Arthur, Merlin

or the devil are accredited with the construction or presence of

prehistoric monuments in Britain.

Moreover, stories of giants exist

right across Asia Minor and the Middle East, and these are often

cited to explain the presence of either cyclopean ruins (such as the

Greek city of Mycenae, the cyclopean walls of which were said to

have been built by the one-eyed cyclops - hence the term 'cyclopean'

masonry) or gigantic natural and man-made features.

On the other hand, the alleged connection between giants, Titans and Baalbek is quite another matter.

It is feasible that, if

the

Watchers and Nephilim (and therefore the

Titans and

giants) are to

be seen as a lost race of human beings, any presumed pre-Phoenician

culture in Lebanon could not have failed to have encountered their

presence in the Near East.

If so,

-

Were alliances forged with them,

wars fought alongside them?

-

Might the ancient skills and brute strength of these human races of

great stature have been employed in grand engineering projects such

as the construction of the Great Platform?

Remember, the Titans were

said to have been born of the same loins as Cronus, and in alliance

with their half-brother, they waged war against their father

Ouranus.

Yet family alliances of this type can go wrong, for

according to the various ancient writers on this subject,(68) after

the fall of the Tower of Babel and the dispersion of the tribes, a

war broke out between Cronus and his brother Titan.

An early

Christian writer named Lactantius (AD 250-325) records that

Titan,

with the help of the rest of the Titans, imprisoned Cronus and held

him safe until his son Jupiter (or Zeus) was old enough to take the

throne.

-

Does this imply that the Titans deposed Cronus and took

control of the Byblos culture until the coming of Zeus, or Jupiter?

-

What influence might this forgotten race have brought to bear on the

development of Lebanon's pre-Phoenician culture?

-

More importantly,

when might any of this have taken place?

Far off in Hell

According to classical mythology, the Titans were eventually

defeated by Jupiter and his fellow Olympian gods and goddesses. As

punishment, they were banished to Tartarus, a mythical region of

hell enclosed by a brazen wall and shrouded perpetually by a cloud

of darkness.

The giants, too, were linked with this terrible

place, for they are cited by the first-century Roman writer Caius

Julius Hyginus (fl. c. 40 BC) as having been the,

'sons of Tartarus

and Terra (ie the earth)'.(69)

Although Tartarus has always been seen as a purely mythical

location, there is reason to link it with a Phoenician city-port and

kingdom known as Tartessus (Tarshish in the Bible) that thrived in

the Spanish province of Andalucia during ancient times.

The evidence is this - Gyges, or Gyes, was a son or Coelus (ie.

Ouranus) and a brother of Cronus; he was also seen both as a gigante

and a Titan (demonstrating how they were originally one and the same

race).(70)

He seems to have been one of the main figures in the

later wars between his titanic brothers and the Olympian gods under

the command of Zeus, and may simply have been Titan under another

name.

Classical writers such as Ovid (43 BC - AD 18) wrote that Gyges was

punished by being banished to the prison of Tartarus. Yet an account

of this same story given by a Chaldean writer named Thallus, states

that instead of being banished to Tartarus, Gyges was 'smitten, and

fled to Tartessus'.(71)

If this is a genuinely separate rendition of

the same story then it means that Tartarus was another name for

Tartessus.

As a sea-port Tartessus it is believed to have been situated on a

delta of the Guadalquivir River, even though no trace of it remains

today. It is also synonymous with another ancient sea-port known as

Gades, modern Cadiz.

E.M. Whishaw in her important 1930 work

Atlantis in Andalucia uses excavated evidence of neolithic and

possibly even palaeolithic sea-ports, sea-walls, cyclopean ruins and

hydraulic works around the towns of Niebla and Huelva on the

Andalucian coast to demonstrate the reality not only of Tartessus's

lost kingdom, but also of its links to Plato's story of Atlantis.

A Sea-faring Nation

Knowledge of the apparent links between Tartessus, the giants/Titans and the mythical Byblos culture is compelling

evidence of an as yet unknown sea-faring nation in the Mediterranean

area sometime between 7000-3000 BC, the latter half of this period

being the time-frame when many of the megalithic complexes began

appearing in places such as Malta and Sardinia.

Charles Hapgood in

his 1979 book

Maps of The Ancient Sea Kings concluded that the

various composite portolans, such as the

Piri Reis map of 1513, show

areas of the globe, including the Mediterranean Sea, as they

appeared at least 6000 years ago.

He therefore concluded that those

who had originally drawn these maps must have belonged to 'one

culture', who possessed maritime connections all over the globe and

flourished during this distant age.(72)

-

Was he referring here to the

mythical Byblos culture?

-

Might it have been responsible for passing

on these ancient maps to civilizations such as Egypt, c.3100 BC, and

Phoenicia, c. 2500 BC?

The early dynastic boat burials uncovered at Giza and Abydos have

revealed sea-going vessels with high prows that were never intended

to be sailed on the Nile; this is despite the fact that Egypt had no

obvious maritime tradition during this early stage in its

development.

-

Where did this knowledge come from?

-

Was it from the

remnants of an earlier culture, such as the one spoken of by Sanchoniatho as having existed on the Levant coast in mythical

times?

-

Might this sea-faring connection help explain why the wooden

coffin containing the body of Osiris was carried by the sea to Byblos, and why the priests of Heliopolis in Egypt took such an

interest in Baalbek during Ptolemaic times?

It is a subject that requires much further research before any

definite conclusions can be drawn, but the apparent advanced

capabilities of the proposed Byblos culture allows us to perceive

the antiquity of Baalbek's Great Platform in a new light.

-

Did the

legends suggesting that it was constructed by super-human giants

during the age of Nimrod preserve some kind of bastardized memory of

its foundation by the Byblos culture under Ouranus, Cronus or his

brothers, the Titans?

-

If so, then who were these mythical

individuals and what ancient engineering skills might their culture

have employed in the construction of cyclopean structures such as

the Great Platform?

Stones that Moved

In surviving folklore from both Egypt and Palestine there are

tantalizing accounts of how sound, used in association with 'magic

words', was able to lift and move large stone blocks and statues, or

open huge stone doors.

I was therefore excited to discover that,

according to Sanchoniatho, Ouranus was supposed to have 'devised Baetulia, contriving stones that moved as having life'.(73)

By

'contriving' the nineteenth-century English translator of Philo's

original Greek text seems to have meant 'designing', 'devising' or 'inventing', implying that Ouranus had made stones to move as if

they had life of their own.

-

Was this a veiled reference to some kind

of sonic technology utilized by the proposed Byblos culture?

-

Could

this knowledge help explain the methods behind the cutting,

transportation and positioning of the 1000-tonne blocks used in Baalbek's Great Platform?

It is certainly a very real possibility.

Why Baalbek?

If we accept for a moment that Baalbek's Great Platform, and perhaps

even the inner podium that supports the Temple of Jupiter, might

well possess a much greater antiquity than has previously been

imagined, then what purpose might the Baalbek structure have served?

Zecharia Sitchin in his 1980 book

The Stairway to Heaven proposes

that the Great Platform was a landing site and launch pad for

extra-terrestrial vehicles.

Perhaps he is right, but in my opinion

its high elevation hints at the fact that it once served as some

kind of platform for the observation of celestial and stellar

events. It is a subject I am currently investigating for a future

article.

And just how old is Baalbek?

The French archaeologist Michel Alouf apparently learnt from the

Maronite Patriarch of the Baalbek region, a man named Estfan

Doweihi, that:

'... the fortress of Baalbek on Mt. Lebanon is the

most ancient building in the world. Cain, the son of Adam, built it

in the year 133 of the creation, during a fit of raving

madness'.(74)

Unfortunately this tells us very little about the

site's real age.

Yet if we can accept the existence of a

pre-Phoenician culture that not only employed the use of cyclopean

masonry in its building construction, but also possessed sea-going

vessels and flourished in the Mediterranean somewhere between 7000

BC and 3000 BC, then it opens the door to the possibility that Baalbek's

'fortress' may also date to this early phase of human

history.

Yet the question remains as to why this pre-Phoenician, sea-going

nation should have wished to construct an almighty edifice on an

elevated plain between two enormous mountain ranges.

What was the

reasoning behind this decision?

The site undoubtedly possessed a

very ancient sanctity; however, the architects may well have had

more pressing reasons for placing it where they did. All the

indications are that Sanchoniatho's Byblos culture eventually

experienced a period of fierce wars that waged between Cronus, or

Saturn, and his titanic brothers under the leadership of Titan or Gyges, and then finally between Cronus' son Jupiter and the rest of

the Olympian deities.

In a strange way the fraternal conflict

between Cronus and his brothers parallels the biblical struggle

between Cain and Abel, suggesting that the link between Cain and

Baalbek might well have some symbolic significance to the site's

early history.(75)

-

Is it possible that Baalbek's first

'city' was constructed, not just

as a religious centre, but also as an impenetrable fortress against

attacks by whatever we see as constituting the gigantes and Titans

of mythology?

-

If the Great Platform, and perhaps even the inner

podium, really does date to this early period, then might the

fortress theory explain why its architects used such gigantic stones

in its construction? Were they incorporated into the design through

a combination of technological capability and sheer necessity, not

through 'the interest of appearance' or some ancient wall-building

tradition upheld by the neo-Phoenicians of the Roman era?

Such ideas

may even provide some kind of explanation as to why the mother of

all stone blocks, the Stone of the Pregnant Woman, was left cut and

ready for transportation in a nearby quarry.

Did the whole building

project have to be abandoned because the site was over-run, or at

least seriously threatened, by invading forces? Scholars have always

accredited the Romans with having built the Great Platform, with its

stupendous Trilithon stones, simply because they could not conceive

of an earlier culture possessing the technological skills needed to

have transported and positioned such enormous weights.

The

Sphinx-building culture of Egypt is evidence that such technological

skills may well have been available as early as 10,500 BC, while our

current knowledge of the Baalbek platform gives us firm grounds to

push back its accepted construction date by at least a thousand

years.

Even if the dates suggested for Sanchoniatho's Byblos culture are

open to question, I believe the sacred fortress hypothesis brings us

a lot closer to unlocking the mysteries of Baalbek.

Both visually

and in legend its ruins bear the mark of the Titans, and

understanding the site's true place in history can only help us to

discover the reality of this lost cyclopean age of mankind.

NOTES

1.

Ragette, Baalbek, p. 33.

2. Ibid., p. 114.

3. Alouf, M. M., History of Baalbek, p. 98.

4. Ibid., p. 39, quoting a story told by Estfan Doweihi, a Maronite

Patriarch.

5. Ibid., p. 41, quoting an Arab manuscript actually found at

Baalbek.

6. Ragette, p. 16.

7. Ibid., p. 27, cf. Kalayan, 1969.

8. Ibid., p. 16.

9. Ibid., p. 16, quoting Josephus.

10. Ibid., p. 17.

11. Alouf, p. 50.

12. Ibid. pp. 42-4.

13. Ragette, p. 19.

14. See Ibid., p. 20 & accompanying pl. on f/p.

15. Ibid., p. 30.

16. Ibid., p. 27.

17. Ibid., p. 30.

18. Ibid., p. 31, cf. Kalayan, 1969.

19. Ibid., pp. 31-2.

20. Alouf, p. 98. The sizes of the blocks from right to left are

given as 65 feet, 64 feet 10 inches and 63 feet 2 inches.

21. Ibid., p. 98

22. Ibid., p. 99

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid., p. 106.

25. Ragette, p. 33.

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid.

28. Ibid., pp. 33-4.

29. Ibid., pp. 34.

30. Ibid., p. 115

31. Ibid., p. 115.

32. Alouf, p. 106, quoting Louis Flicien de Saulcy.

33. Ibid., p. 115.

34. Ibid., p. 115.

35. Ibid., p. 33.

36. Ibid., p. 119.

37. Ibid., p. 116.

38. Ibid.

39. Ibid., p. 94.

40. See Renan, 1864.

41. Ragette, p. 94.

42. Ibid., p. 94.

43. Ibid.

44. Cory, p. viii.

45. Sanchoniatho, quoted by Cory., p. 9.

46. Ibid., p. 7.

47. Ibid., p. 11.

48. Ibid., p. 14.

49. Ibid., p. 14.

50. Ibid.

51. Budge, The Egyptian Book of the Dead, p. l.

52. Ibid.

53. Ibid., p. l, n 3.

54. Ibid., p. l.

55. Herm, The Phoenicians, p. 114

56. Ibid.

57. Ibid.

58. See Hancock,

Fingerprints of the Gods, 1995; Bauval & Hancock,

Keeper of Genesis, 1996; Collins, From the Ashes of Angels, 1996.

59. Alouf, p. 32

60. Ibid., p. 47-8, cf. Macrobius, Saturnalia, L.I.C. 23.

61. Ibid., p. 47, cf. Volney, Voyage en Syrie, p. 228.

62. Ibid., cf. De De

' Syriae & Macrobius, L.I.C. 23.

63. See, for instance, Gen. 6:1-2,4.

64. See the author's From the Ashes of Angels, Ch. 16.

65. See, for instance, the works of Berossus, Eupolemus, Alexander

Polyhistor and the Sibylline Oracles, as quoted by Cory.

66. Alouf, p. 41.

67. Ibid., quoting a traveller named d'Arvieux' from his M moires,

Part IIe, Ch. 26, c. 1660.

68. See, for instance, Berossus, Alexander Polyhistor and the

Sibylline Oracles quoted by Cory.

69. Lempriere, Classical

Dictionary, c.v. 'Gigantes', p. 249.

70. Ibid. & Eupolemus, quoted in Cory, p. 53.

71. Thallus, quoted by Cory, p. 53

72. Hapgood, Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings, p. 221.

73. Sanchoniatho, quoted in Cory, p. 10.

74. Alouf, p. 39.

75. Indeed, local tradition asserts that the region around

Baalbek

was the stamping ground of Genesis characters such as Adam and his

sons Abel, Cain and Seth. See Ibid., p. 39. The reality of such

myths is quite another matter, especially as equally strong

traditions associate the pre-Flood events of the Book of Genesis

with Turkish and Iraqi Kurdistan.

Bibliography

-

Alouf, Michel M., History of Baalbek, 1890, American Press, Beirut,

1953

-

Bauval, R, & G. Hancock, Keeper of Genesis, Wm Heinemann, London,

1996

-

Budge, E. A. Wallis,

The Egyptian Book of the Dead, 1895, Dover

Publications, NY, 1967

-

Collins, A., From the Ashes of Angels, Michael Joseph, London, 1996

-

Cory, I. C., Ancient Fragments, 1832, Wizards Bookshelf,

Minneapolis, 1975

-

Hancock, G.,

Fingerprints of the Gods, Wm Heinemann, London, 1995

-

Herm, Gerhard, The Phoenicians, 1973, Futura, London, 1975

-

Kalayan, H., 'Notes on the Heritage of Baalbek and the Beqa'a' in

Cultural Resources in Lebanon, Beirut, 1969

-

Lempriere, J., A Classical Dictionary, Geo. Routledge, London, 1919

-

Ragette. F., Baalbek, Chatto & Windus, London, 1980

-

Renan, E., Mission de Phonicie, Paris, 1864

-

Whishaw, E. M., Atlantis in Andalucia, Rider, London, 1930

|