|

from

PBS Website

Felipe holds the head of his daughter Maria Geovana, who has microcephaly, at his house in Recife, Brazil, Jan. 25, 2016. Health authorities in the Brazilian state at the center of a rapidly spreading Zika outbreak have been overwhelmed by the alarming surge in cases of babies born with microcephaly, a neurological disorder associated to the mosquito-borne virus. Photo by Ueslei Marcelino/Reuters

Zika. Zika. Zee-kah...

You've heard about how this mosquito-borne virus is barreling through the southern Americas, namely Brazil, and how it's potentially linked to microcephaly, a condition wherein newborns are born with shrunken heads and severe disability.

That's scary, and many parents in the U.S. are worried about the disease gaining a foothold on these shores.

The WHO (World Health Organization) said Thursday the virus could infect up to 4 million people this year. Since the Zika outbreak first sprouted in Brazil in May 2015, the country has notched around 4,000 cases of microcephaly.

Before 2015, the country had fewer than 200 cases per year.

But did you know there's already another virus in the U.S. associated with tens of thousands of cases of brain defects, including microcephaly, each year? And much like Zika, there's no cure or vaccine. (More on that later...)

And there are so many other questions, making this possibly the most frustrating medical challenge of 2015 and 2016:

We reached out to the experts for answers to this and other questions.

But let's start with the basics:

What is Zika virus and how might it disintegrate a developing brain?

A sterile female Aedes aegypti mosquito is seen in a research area to prevent the spread of Zika virus and other mosquito-borne diseases, at the entomology department of the Ministry of Public Health, in Guatemala City, January 28, 2016. Photo by Josue Decavele/Reuters

Zika is a flavivirus, which is pronounced a bit a like flavor. Flay-v-virus.

Most viruses in this family are carried by arthropods - mosquitoes and ticks. We've known about Zika virus since at least 1947, when researchers from the Rockefeller Foundation put a rhesus monkey in a cage in the middle of Zika Forest of Uganda.

The team was conducting surveillance for yellow fever.

But "Rhesus 766" would ultimately become the first known carrier of Zika virus (it remains unconfirmed if monkeys or other animals are consistent carriers - or reservoirs - for the disease).

Over the next decades, cases would be reported in humans throughout many nations in Africa and Asia. Symptoms are mild - a fever, joint pain, sometimes a rash or pink eye - but the disease typically clears within a week.

The virus eventually jumped from Africa/Asia and landed in Yap Island in 2007, French Polynesia in 2013, and South America in 2014.

The first case in the Americas was reported in Chile's Easter Island in February 2014, and the virus spread to Brazil, where it's been linked to an uptick in neurological disease, such as microcephaly, as well as the adult paralysis disorder, Guillain-Barré syndrome.

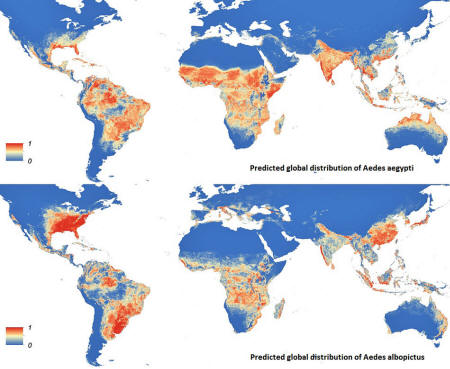

Two types of mosquitoes found in the Americas,

...have been implicated in large outbreaks of Zika virus, though Aedes aegypti is the primary culprit in Brazil and other tropical areas.

But how do viruses like Zika change the fate of a nervous system, namely one developing in a fetus? The clues may rest with a plethora of other viruses associated with microcephaly.

Take cytomegalovirus, for example.

Could mothers receive a blood transfusion to prevent the disease?

About one in 750 children in the United States is born with or develops permanent problems due to CMV infection during pregnancy, according to the CDC (Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.)

A national survey in 1995 found close to 40 percent of congenital CMV cases - those detected at birth - may experience microcephaly.

In general, more than 5,000 U.S. children per year suffer permanent problems caused by CMV infection during pregnancy. CMV spreads by direct contact with bodily fluids - urine, saliva, or breast milk - and not mosquitoes.

But how?

Katherine Spindler says the connection between CMV and brain abnormalities isn't completely understood, but one study suggests that the virus attacks stem cells during early brain development while also causing the general destruction of other brain tissue. The early loss of stem cells may keep a fetal brain from forming the correct architecture.

You may have heard of another virus linked to microcephaly: Rubella.

It represents the "R" in the MMR vaccine. Thanks to this drug, Rubella is no longer a widespread threat to infants. There are only 100,000 cases per year worldwide of congenital rubella.

There's too little research to tell if Zika virus does the same thing to infants as CMV, as it isn't clear if Zika is the only mosquito-borne virus responsible for the microcephaly outbreak.

Zika's cousin, chikungunya virus has also been associated with microcephaly, Spindler said, which brings us to our next question.

How do you diagnose Zika, and can microcephaly be caught in time to terminate a pregnancy (if desired)?

A government poster campaign informing about Zika virus symptoms is seen on the wall as a doctor performs a routine general check up for a pregnant woman, which includes Zika virus screening, at the maternity ward of a hospital in Guatemala City, Guatemala, January 28, 2016. Photo by Josue Decavele/REUTERS

Genetic testing for the presence of Zika virus is the only surefire way to know if a mother has caught the infection, but regardless, doctors still struggle to spot the disease.

The challenge is this:

The WHO has called an emergency committee meeting Monday to coordinate an action plan.

Once the virus clears the body, it shouldn't be a threat to women who might want to become pregnant.

But the symptoms of the infection are mild and only last a week, reducing the odds of a genetic test being given while a patient is still ill. The infection must be caught while a significant amount of virus is still circulating in the body, otherwise it'll be missed.

This is part of why scientists haven't confirmed if Zika virus is responsible for Brazil's uptick in microcephaly cases.

Only six of the 4,000 microcephaly cases in the country have been strongly linked to Zika virus via laboratory confirmation that the germ's genetic material is present in the infant, Scientific American reported.

Doctors have found Zika genetic material in fetal tissue from early missed abortions, amniotic fluid surrounding the fetus and in the brains of newborns with microcephaly.

However, Spindler and Daniel Lucey say the key to proving causality between Zika virus and microcephaly may only come from detecting the infection in the absence of other infections.

Both dengue and chikungunya flashed through South America immediately before microcephaly plagued Brazil, so those diseases may be at fault too, either by predisposing kids for the mental condition or directly causing it.

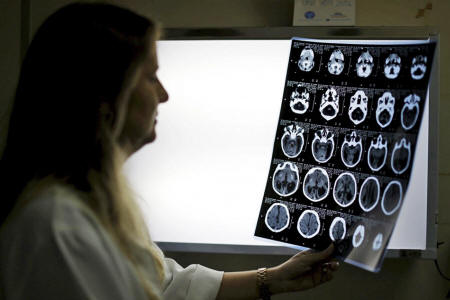

Child Neurologist Vanessa Van Der Linden observes the X-ray of a baby's skull with microcephaly at the hospital Barao de Lucena in Recife, Brazil, January 26, 2016. Photo by Ueslei Marcelino/REUTERS

The greatest risk of microcephaly and malformations appears to be associated with a Zika infection happening during the first trimester of pregnancy, according to the Pan American Health Organization.

Genetic testing plus amniocentesis - a sampling of the amniotic fluid - may reveal a fetal infection with Zika virus as early as 15 weeks of gestation, according to the ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,) but earlier time frames may endanger the baby.

The earliest that microcephaly can be detected, regardless of the cause, is late in the second trimester of gestation (18 to 20 weeks), according to the CDC.

The ACOG also lists screening of Zika-fighting antibodies as a possible way to confirm if a person had an infection, but this isn't a feasible solution for much of the Americas, including the U.S.

The same issue happens due to West Nile virus, which has perpetuated through much of the U.S. since 1999.

Could mothers receive a blood transfusion to prevent the disease?

Though it does work for other diseases, such as 'hepatitis A', said Scott Weaver, director of the Institute for Human Infections and Immunity at the University of Texas Medical Branch.

But he continued that transferring immunity via a blood transfusion isn't the best or simplest solution.

For instance, while the strategy was touted mightily during the Ebola outbreak, the latest studies suggest the technique wasn't effective.

Are mosquitoes the only way to catch Zika?

As far as anyone knows, yes.

But two cases have been potentially linked to sexual activity. The first - detailed in 2011 Science Magazine story titled "Sex After a Field Trip Yields Scientific First" - involved a U.S. biologist who caught Zika virus while working in Senegal. Upon returning to Colorado, the researcher developed symptoms of Zika - and a few days later, the same happened to his wife.

Yet it's unclear if the Zika virus was actually reproducing in his testicles, as this patient also suffered from hematospermia, wherein blood leaks into the semen. Gross, I know, but a similar case was reported on the French Polynesian island of Tahiti in 2013.

However, just how two pies don't make a party, two isolated incidents don't confirm that Zika virus is sexually transmitted. Spindler said further analysis is needed to make the argument, and for now, public health officials should focus on mosquito control to stop Zika virus.

And with that said…

A vaccine isn't the fastest option for stopping Zika virus and microcepaly

Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images

You're right: that isn't a question, but the assertion is true.

A vaccine would keep people from catching the virus, while also preventing mosquitoes from transmitting further cases.

Drugmakers like, ...are champing to lead the way.

But production of a vaccine could take years or decades, and there are potentially faster options for stemming Zika.

Prior to Georgetown, Lucey spent three years reviewing possible vaccines at the FDA, and he said there are oodles of vaccine candidates submitted for review that never, ever end up getting licensed.

An attenuated vaccine is really just a virus with a reduced potency for causing its disease.

It contrasts with an inactivated vaccine, where the virus is killed. Both can establish an immunity against a disease, but Lucey said expecting mothers might be hesitant to take an attenuated vaccine for Zika virus. Plus they can take a long time to develop.

The first vaccine for the dengue flavivirus - also an attenuated vaccine - was just approved last month for use in Brazil, Mexico and the Philippines, nearly 20 years after the project started.

Lucey believes a vaccine would be wonderful tool for halting Zika virus, but the more immediate focus should be mosquito control.

Reducing mosquito breeding sites and insecticides are some of the best established stopgaps for preventing diseases like Zika, as well as using mosquito nets and wearinglong-sleeved shirts and long pants.

Genetically modified mosquitoes have also been employed in Brazil to fight Zika virus.

Another expedient alternative is monoclonal antibodies. You've probably heard of these before - remember the drug Zmapp for Ebola?

Humans make these antibodies as part of their natural process of building immunity against a disease, but scientists can also engineer them.

In fact, there's already a lab in the U.S. with 10 candidates for Zika virus.

The main advantage of a monoclonal antibody is that it could be given to a mother after she had already caught Zika virus to stem the course of the disease.

The antibody candidates in Michael Diamond's lab are still in their early stages of being tested in cells grown in petri dishes, but he said antibody therapies can be developed in less time than vaccines, because there are typically fewer safety issues.

Both Diamond and Weaver said an antibody therapy can likely be developed in less time than a vaccine.

The predicted global distribution of Aedes aegypti (top) and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes. Both can transmit Zika virus. Red indicates areas with a high occurrence rate of the mosquito species; blue represents areas with low occurrence rate. Photo by Kraemer MUG et al. eLife 2015;4:e08347

|