|

by Fritjof Capra

From my early student years, I was fascinated by the dramatic changes of concepts and ideas that occurred in physics during the first three decades of the twentieth century.

In my first book,

The Tao of Physics (Capra, 1975), I

discussed the profound change in our worldview that was brought

about by the conceptual revolution in physics - a change from the

mechanistic worldview of Descartes and Newton to a

holistic and ecological view.

To connect the conceptual changes in science with the broader change of worldview and values in society, I had to go beyond physics and look for a broader conceptual framework.

In doing so, I realized that our major social issues,

...all have to do with living systems; with individual human beings, social systems, and ecosystems.

Using insights from the theory of living systems, complexity theory, and ecology, I began to put together a conceptual framework that integrates four dimensions of life: the biological, the cognitive, the social, and the ecological dimension.

I presented summaries of

this framework, as it evolved over the years, in several books,

beginning with The Turning Point (Capra, 1982), and followed by

The

Web of Life (Capra, 1996) and The Hidden Connections (Capra, 2002).

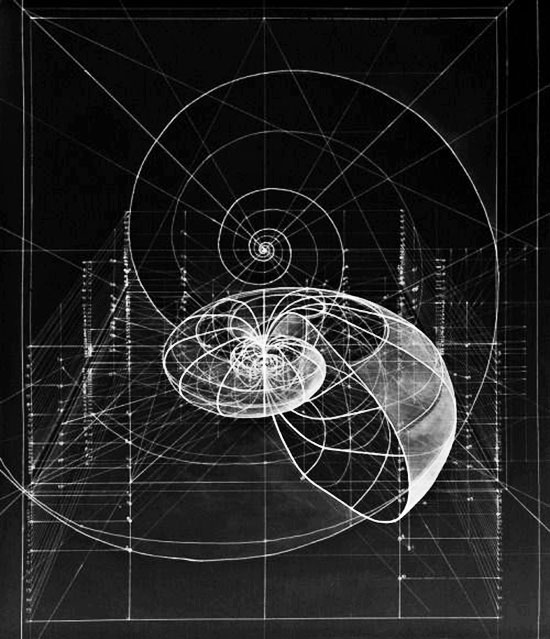

At the very heart of it, we find a fundamental change of metaphors:

We are starting to see the world as a network.

We have discovered that the material world, ultimately, is a network of inseparable patterns of relationships. We have also discovered that the planet as a whole is a living, self-regulating system.

The view of the human

body as a machine and of the mind as a separate entity is being

replaced by one that sees not only the brain, but also the immune

system, the bodily organs, and even each cell as a living, cognitive

system. And with the new emphasis on complexity, nonlinearity, and

patterns of organization, a new science of qualities is slowly

emerging.

In science, this way of thinking is known as 'systems thinking', or 'systemic thinking'.

The systems view of

evolution

Rather than seeing evolution as the result of only random mutations and natural selection, we are beginning to recognize the creative unfolding of life in forms of ever-increasing diversity and complexity as an inherent characteristic of all living systems.

Although mutation and

natural selection are still acknowledged as important aspects of

biological evolution, the central focus is on creativity, on life's

constant reaching out into novelty.

Our detailed ideas about

this

prebiotic evolution are still very speculative, but most

biologists and biochemists do not doubt that the origin of life on

Earth was the result of a sequence of chemical events, subject to

the laws of physics and chemistry and to the nonlinear dynamics of

complex systems.

These tiny droplets

formed spontaneously according to the basic laws of physics, as

naturally as the soap bubbles that form when we put soap and water

together and shake the mixture.

Eventually life emerged

from these protocells with the evolution of the DNA, proteins, and

the genetic code.

The descendants of the

first living cells took over the Earth by weaving a planetary

bacterial web and gradually occupying all the ecological niches.

From the beginning of life, their interactions with one another and with the nonliving environment were cognitive interactions (ibid., pp. 141ff.).

As their structures

increased in complexity, so did their cognitive processes,

eventually bringing forth conscious awareness, language, and

conceptual thought.

Aarti puja by the Ganga

Spirit and

spirituality

To answer this question, it is useful to review the original meaning of the word 'spirit'.

The common meaning of

these key terms indicates that the original meaning of spirit in

many ancient philosophical and religious traditions, in the West as

well as in the East, is that of the breath of life.

Spirituality is usually understood as a way of being that flows from a certain profound experience of reality, which is known as 'mystical', 'religious', or 'spiritual' experience.

There are numerous descriptions of this experience in the literature of the world's religions, which tend to agree that it is a direct, non-intellectual experience of reality with some fundamental characteristics that are independent of cultural and historical contexts.

One of the most beautiful

contemporary descriptions can be found in a short essay titled

Spirituality as Common Sense,

by the Benedictine monk, psychologist, and author David

Steindl-Rast (1990).

Our spiritual moments are moments when we feel intensely alive.

The aliveness felt during such a 'peak experience', as psychologist Abraham Maslow (1964) called it, involves not only the body but also the mind. Buddhists refer to this heightened mental alertness as 'mindfulness', and they emphasize, interestingly, that mindfulness is deeply rooted in the body.

Spirituality, then, is always embodied.

We experience our spirit, in the words of Brother David, as,

It is evident that this notion of spirituality is very consistent with the notion of the embodied mind that is now being developed in cognitive science (see Varela et al., 1991).

Spiritual experience is an experience of aliveness of mind and body as a unity.

Moreover, this experience

of unity transcends not only the separation of mind and body, but

also the separation of self and world. The central awareness in

these spiritual moments is a profound sense of oneness with all, a

sense of belonging to the universe as a whole.

As we understand how the roots of life reach deep into basic physics and chemistry, how the unfolding of complexity began long before the formation of the first living cells, and how life has evolved for billions of years by using again and again the same basic patterns and processes, we realize how tightly we are connected with the entire fabric of life.

Spiritual teachers throughout the ages have insisted that the experience of a profound sense of connectedness, of belonging to the cosmos as a whole, which is the central characteristic of mystical experience, is ineffable - incapable of being adequately expressed in words or concepts.

Thus we read in the

Kena Upanishad (see Hume,

1934):

We know not, we understand not

Scientists, in their systematic observations of natural phenomena, do not consider their experience of reality as ineffable. On the contrary, we attempt to express it in technical language, including mathematics, as precisely as possible.

However, the fundamental interconnectedness of all phenomena is a dominant theme also in modern science, and many of our great scientists have expressed their sense of awe and wonder when faced with the mystery that lies beyond the limits of their theories.

Albert Einstein, for one, repeatedly expressed these feelings, as in the following celebrated passage (Einstein, 1949).

There are three basic aspects to religion:

In theistic religions, theology is the intellectual interpretation of the spiritual experience, of the sense of belonging, with God as the ultimate reference point.

Morals, or ethics, are the rules of conduct derived from that sense of belonging; and ritual is the celebration of belonging by the religious community.

All three of these aspects - theology, morals, and ritual - depend on the religious community's historical and cultural contexts.

Theology

Indeed, according to the Benedictine scholar Thomas Matus (quoted in Capra and Steindl-Rast, 1991), during the first thousand years of Christianity virtually all of the leading theologians - the so-called 'Church Fathers' - were also mystics.

Over the subsequent

centuries, however, during the scholastic period, theology became

progressively fragmented and divorced from the spiritual experience

that was originally at its core.

Whereas the Church Fathers repeatedly asserted the ineffable nature of religious experience and expressed their interpretations in terms of symbols and metaphors,

In other words, Christian

theology (as far as the religious establishment was concerned)

became more and more rigid and fundamentalist, devoid of authentic

spirituality.

While scientists try to explain natural phenomena, the purpose of a spiritual discipline is not to provide a description of the world. Its purpose, rather, is to facilitate experiences that will change a person's self and way of life.

However, in the interpretations of their experiences mystics and spiritual teachers are often led to also make statements about the nature of reality, causal relationships, the nature of human consciousness, and the like.

This

allows us to compare their descriptions of reality with

corresponding descriptions by scientists.

In a way, these descriptions are not unlike the limited and

approximate models in science, which are always subject to further

modifications and improvements.

This rigid position of the Church led to the well-known conflicts between science and fundamentalist Christianity, which have continued to the present day.

In these conflicts, antagonistic positions are often taken on by fundamentalists on both sides who fail to keep in mind the limited and approximate nature of all scientific theories, on the one hand, and the metaphorical and symbolic nature of the language in religious scriptures, on the other.

Thus Dionysius the Areopagite, a highly influential mystic of the early sixth century, writes:

Saint John of Damascus in the early eighth century:

(Both quoted in Capra and Steindl-Rast, 1991).

The central error of fundamentalist theologians in subsequent centuries was, and is, to adopt a literal interpretation of these religious metaphors.

Once this is done, any dialogue between religion and science becomes frustrating and unproductive.

Religion involves not only the intellectual interpretation of spiritual experience, but is also closely associated with morals and rituals.

Morals, or ethics,

are the rules of conduct derived from the sense of belonging that

lies at the core of the spiritual experience, and ritual is the

celebration of that belonging.

When we belong to a community, we behave accordingly.

we belong to many different communities,

We are all members of humanity,

To spell this out in detail is quite a challenge, but fortunately we have a magnificent document, the Earth Charter, which covers the broad range of human dignity and human rights.

The

Earth Charter was written over many years, beginning with the

Earth Summit in Rio de

Janeiro

in 1992, in a unique collaborative effort involving NGOs,

indigenous peoples, and many other groups around the world. It is a

declaration of 16 values and principles for building a sustainable,

just, and peaceful world - a perfect summary of the ethics we need

for our time.

The original purpose of religious communities was,

For this purpose, religious leaders designed special

rituals within their historical and cultural contexts.

In many religions, these special means to facilitate mystical experience become closely associated with the religion itself and are considered sacred.

Thus, we hear of,

However, in their different pursuits,

both are led to make statements about

the nature of reality that can

be compared.

In the 1950s, several of these scientists published popular books about the history and philosophy of quantum physics, in which they hinted at remarkable parallels between the worldview implied by modern physics and the views of Eastern spiritual and philosophical traditions.

The worldview of quantum physics and Eastern spiritual traditions turned out to be remarkably similar.

The following three

quotations are examples of such early comparisons.

During the 1960s, there was a strong interest in Eastern spiritual traditions in Europe and North America, and many scholarly books on Hinduism, Buddhism, and Taoism were published by Eastern and Western authors.

At that time,

the parallels between these Eastern traditions and modern physics

were discussed more frequently (see, e.g., LeShan, 1969), and a few

years later I explored systematically in

The Tao of Physics (Capra,

1975).

To begin with, their method is thoroughly empirical.

The objects of observation are of course very different in the two cases.

Exploring ever deeper realms of matter, they become aware of the essential unity of all natural phenomena.

More than that, they also realize that they themselves and their consciousness are an integral part of this unity. Thus mystics and physicists arrive at the same conclusion; one discipline starting from the inner realm, the other from the outer world.

The harmony

between their views confirms the ancient Indian wisdom that

brahman,

the ultimate reality without, is identical to atman, the reality

within.

In both cases,

access to these non-ordinary levels of experience is possible

Subsequently, the same change of paradigms occurred in the life sciences with the gradual emergence of the systems view of life.

It

should therefore not come as a surprise that the similarities

between the worldviews of physicists and Eastern mystics are

relevant not only to physics but to science as a whole.

Other authors extended their inquiries beyond physics, finding similarities between Eastern thought and certain ideas about free will; death and birth, and the nature of life, mind, consciousness, and evolution (see Mansfield, 2008).

Moreover, the same kinds of parallels have been drawn also to Western mystical traditions (see Capra and Steindl-Rast, 1991).

We are deeply connected to nature.

Hence, there are numerous similarities between

the worldviews of mystics and spiritual teachers - both Eastern and

Western - and the systemic conception of nature that is now being

developed in several scientific disciplines.

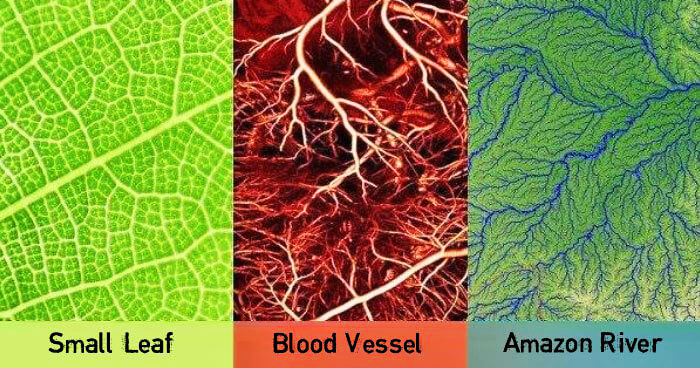

Connectedness, relationship, and interdependence are fundamental concepts of ecology; and connectedness, relationship, and belonging are also the essence of spiritual experience.

Hence, ecology - and in particular the school of deep ecology, founded by the Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess in the 1970s (see Devall and Sessions, 1985) - can be an ideal bridge between science and spirituality.

The defining characteristic of deep ecology is a shift from anthropocentric to ecocentric values.

It is a worldview that acknowledges the inherent value of non-human life, recognizing that all living beings are members of ecological communities, bound together in networks of interdependencies.

Every molecule in our body was once a part of previous bodies - living or nonliving - and will be a part of future bodies. In this sense, our body will not die but will live on, again and again, because life lives on.

Moreover, we share not only life's molecules, but also its basic principles of organization with the rest of the living world. And since our mind, too, is embodied, our concepts and metaphors are embedded in the web of life together with our bodies and brains.

Indeed, we belong to the Universe, and this experience of belonging can make our lives profoundly meaningful...

|