|

New Dawn 145 July-August 2014 from NewDawnMagazine Website

An austere, world-denying sect, they were nevertheless associated with a remarkable cultural renascence in the southern France of the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries.

Beloved in the regions that supported them, they were popularly known as the bonshommes, the "good men."

Labeled by

the Catholics as "the great heresy," Catharism was so

formidable a rival that the church formed

the Inquisition to crush it.

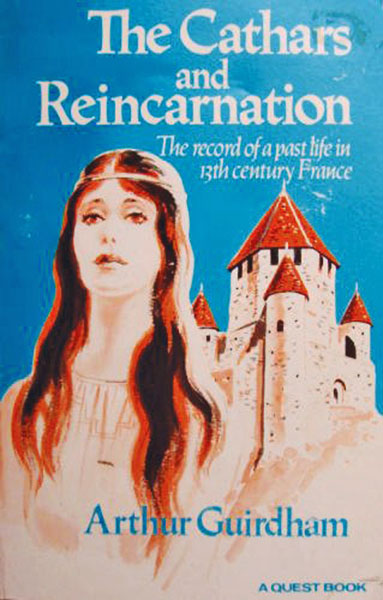

is told in his book

The

Cathars and Reincarnation

Their origins are obscure, but they appear to have some connection with sects that stretched back at least to the time of Christ, with exotic names such as the,

I cannot sketch out this

history here (I have tried to do so in my book

Forbidden Faith - The Secret History of

Gnosticism), but it is probably safe to say that some

kind of continuous link connects all these groups spanning the first

millennium of the Common Era.

This word has many meanings. Here it means the belief in a cosmos that is made up of two opposing and more or less equipotent forces:

This polarity is cosmic:

Our world, the world of

matter, is the creation of the dark forces; the light is imprisoned

and alien here.

By the old Catholic

axiom, natura vulnerata, non deleta - "nature was wounded but

not destroyed" by the Fall.

One obvious example is the pathological hatred of the body that Christianity has shown almost since its earliest days.

Conventional Christianity may not teach that the world is evil, but it frequently acts as if it is. And while Christianity claims that the sole and ultimate power is good, it also makes the Devil and his minions seem very nearly as powerful.

Some scholars even say

that Christianity is semidualistic.

You can read a great deal about the subject and still be left groping for an answer.

The scholarly books,

however serious and exhaustive, offer no real clue to this puzzle;

the authors themselves often seem baffled by it.

A Psychiatrist's Past-Life Memories

(1905-92)

Arthur Guirdham (1905-92) was born in Cumbria, England, the son of a steelworker.

By sacrificing the education of his sisters, his parents were able to give him a decent enough education so that he was able to attend the University of Oxford. Eventually he qualified as a psychiatrist.

He was practicing in this capacity in 1962 when he met a patient that he calls Mrs. Smith.

His first words to her (as he would be reminded later, to his own surprise) were,

Mrs. Smith, an otherwise normal woman in her early thirties, came to him with a complaint about a recurring dream that had been disturbing her:

Although in itself,

He had been having a similar recurring nightmare in which,

Although he could not remember exactly when his nightmares had started, he was certain about when they ended:

Moreover, as he later learned, her dreams of this kind stopped as well.

For the next year, curious coincidences and synchronicities continued to occur linking Guirdham, Mrs. Smith and the Cathars.

Then, in a session in December 1964, Mrs. Smith made a remark to the effect that,

She attributed this

statement to Guirdham himself, even though he was sure he had never

said any such thing.

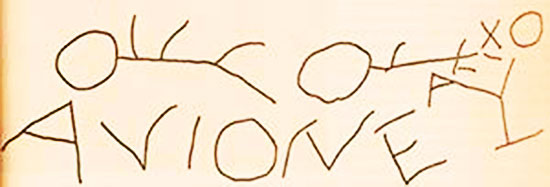

made this drawing when she was seven years old. It is said to depict two Inquisitors killed by the Cathars, as well as an English child's attempt to render "Avignonnet" - a site were Cathars were massacred -

in her

own language. Mrs. Smith then revealed a startling fact.

When she was a teenager

she had written a novel, which she later destroyed, about life in a

medieval women's community and a man she loved named Roger.

But she was not sure

whether this was a person or a place.

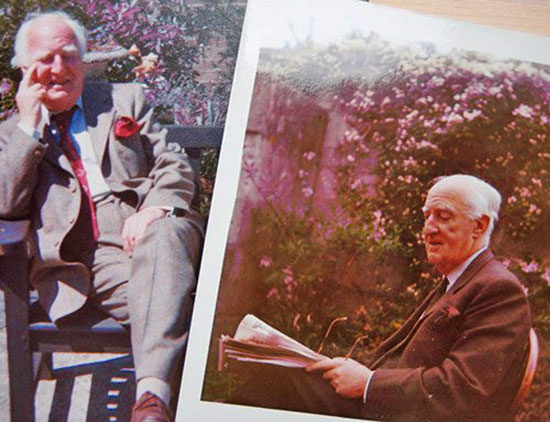

Soon after Mrs. Smith's revelations about her past life as a Cathar, other women started coming forward with similar flashbacks and detail, leading Dr. Arthur Guirdham to believe he was witnessing an unbelievable occurrence: mass reincarnation. The above photo of Dr. Guirdham with some of his incarnated soul group was taken at Montségur, France in the 1970s.

It developed that a certain Fabrissa de Mazerolles was a well-known protector of heretics (i.e., Cathars) in early thirteenth-century Languedoc.

The identity of the man in Guirdham's and Mrs. Smith's dreams also became clear:

Although Mrs. Smith, or her previous incarnation (named Peirone or Puerilia), was frightened by her memory of Pierre, he had not meant to harm her.

He had come to announce

gleefully that he had committed murder.

But it did provoke a reprisal that ended in the climactic siege of Montségur in 1244, the most famous episode in the Cathar epic, which ended with two hundred parfaits being burned alive, and marked the beginning of the end for Catharism as a movement.

(Pierre de Mazerolles,

incidentally, was not a Cathar; he was motivated by greed and by the

sheer joy of murder.)

Many other characters are

introduced, a number of whom can be identified from historical

records but who begin to blur together in the narrative.

Peirone suffered a more dramatic fate, and one of the most memorable passages of Guirdham's books gives her first-person recollection of being burned at the stake:

As compelling as this is, does it stem from an overactive imagination?

The answer lies in the historical veracity of many details in this bizarre story.

Mrs. Smith knew many things that she could not have known from her conventional education; indeed some of them were not discovered until after her experiences.

The parfaits were the elite, the few who had received the initiation known as the Consolamentum and who served more or less as a clergy. Most of the books say they always wore black robes.

But Mrs. Smith remembers that Roger's were dark blue...

It was only several years after these revelations that Guirdham came across a statement in La vie quotidienne des Cathares du Languedoc au XIIIe siècle ("The Daily Life of the Cathars in Languedoc in the Thirteenth Century") by the well-known scholar René Nelli that, although the parfaits had originally worn black, they often switched to dark blue as a disguise in times of persecution.

Since Mrs. Smith's memories were of those days of persecution, this would make sense. This detail had not appeared in print when she had her dreams.

Nelli, whom Guirdham

consulted, was so struck by the accuracy of her recollections that

he told him that when in doubt about some detail he should trust the

memory of the patient.

She had transcribed them when she was a teenager. Moreover, some of her verses strongly resemble those in anthologies of medieval French poetry.

She only knew a little French, which she had studied at school, and had no knowledge of Languedoc (the Romance dialect spoken in that region) or of medieval French.

But, for example, in her

verses she uses the word foliete for "foliage." The French

equivalent, which she would have learned at school, is verdure, but

the word in Provençal, a language close to that of Languedoc, is

folhet.

Of Peirone's house, she recalls,

She and her family slept in their clothes on the floor.

Frequently she gives

details about medieval life that Mrs. Smith knew nothing about, such

as the custom of drinking diluted wine.

It would be more interesting to see what we can learn from these accounts, and how they supplement conventional sources on Catharism.

Guirdham's answer is clear and sensible.

The Cathar parfaits were extremely strict with themselves:

Those demands were only made of the parfaits.

Unlike the Catholic priests of the time, the parfaits actually lived up to their vows; thus they won the affection of the people, and the nickname bonshommes.

But ordinary believers -

the croyants - were under no such obligations. The demands made on

them were light.

They also believed that the world of matter was fundamentally evil (a case that is easy to make). But unlike the Catholics, they did not cling to the gloomy and improbable doctrine of eternal damnation.

Guirdham writes:

This view helps explain how the supposedly somber Cathars were able to thrive in, and foster, the lively and cheerful civilization of Languedoc.

The world is evil, so

one does not need to take it too seriously, and certainly there

is no point in making things worse than they already are.

There was no Cathar wedding ceremony, and many Cathar couples lived in what the Catholics would call 'sin.'

It is clear from Mrs. Smith's evidence that Roger and Peirone were not married either.

(Actually this was in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, earlier than the time of persecution that we have been discussing, in the thirteenth century.)

Courtly love, a

kind of intense love from afar that was usually unconsummated, was

the inverse of marriage: it was often practiced between a man and a

woman of divergent social classes, it was not for the purpose of

having children, and it was, at least ostensibly, chaste.

Guirdham mentions the tradition that says the troubadour poets would wear a rose when singing songs with esoteric themes; when they did not, the songs were about ordinary human love.

Denis de Rougemont, in his influential book Love in the Western World, argues that the troubadours invented what we now call romantic love.

This view is hard to sustain. Greek lyric and Roman elegiac poetry show people in love much as they are today.

But de Rougemont may be right to this extent:

The Cathars' indifference to marriage resembles the attitude of another religion that may be called world-denying.

The Buddhists have no marriage ceremony as such. Monks do not marry a couple; the couple marry each other; a monk may bless the ceremony, but he does not perform it.

This peculiar fact may

have something to teach about world-denying religions and their fate

in the world, particularly in the West.

Religion holds society together; at least that is how it worked in the past.

If, however, religion is to do this, it must take society's concerns somewhat seriously. A religion that regards the world as ultimately rather unimportant is not likely to be enthusiastic about taking on the role of guarantor of the social order.

This attitude may help explain why dualistic movements such as the Cathars and the Manichaeans never established any long-lasting dominance in societies and nations.

It is true that Buddhism, which is also somewhat world-denying, has managed to establish itself, but it is striking that a number of Buddhist nations have continued to use native traditions,

...to continue to fill some social functions.

But at this point we may turn to another dimension of Guirdham's portrait:

These teachings, assembled in the final section of Guirdham's book The Great Heresy, deal with subjects ranging from the,

These things do not, on the face of it, strike one as part of Catharism.

On the other hand, they

do not contradict what we know about the Cathars either. In their

way, like the rest of Guirdham's work, they serve to fill out its

portrait.

But they had another important function:

Guirdham points out that one of Christ's original commands to his followers was to heal the sick.

The parfaits did this

using a number of techniques, including what we today would call

bodywork and administering herbs and tinctures. Guirdham also

discusses the use of jewels in healing, although he acknowledges

that they are not as useful for this purpose as they were in bygone

ages, when people were more psychically sensitive.

Plants have auras like human beings, and when, in certain instances, a person finds a certain plant, like a tree, to give off a healing quality, it is the result of this aura. Guirdham himself recalled the case of an old miner who was subject to periodic bouts of depression.

At these times he would go off and sit under a particular roadside tree, and afterwards he felt better.

But plants can have negative properties as well; some thrive on maleficent vibrations, including perhaps toadstools and fungi that thrive in dank underground cellars.

Guilhabert makes the arresting remark that evil can insert itself in nature, citing as an example the lurid aniline-dye colors of recently developed varieties of roses.

Some of these remarks are reminiscent of the ideas of the Austrian visionary Rudolf Steiner, who also spoke of the etheric bodies and auras of plants.

This may not be a complete coincidence.

Steiner laid claim to the heritage of the Rosicrucian brotherhood of the seventeenth century, and Guirdham suggests that the Rosicrucians may have been the spiritual descendants of the Cathars.

Conventional scholarship says they did not. But there may be some evidence of underground Cathar survivals.

In a persuasive book called The Secret Heresy of Hieronymus Bosch, author Lynda Harris suggests that the great Netherlandish painter and forerunner of surrealism may have been secretly a Cathar two hundred years after the faith supposedly perished.

Harris's argument is too

intricate to go into here, but the facts that

Bosch's ancestral home was the

town of Aachen, a former Cathar centre, and that many of his bizarre

images have curiously heterodox implications, suggests the Cathars

may not have perished as thoroughly as the Inquisitors wished.

These lost, half-forgotten faiths - the Cathars, the Manichaeans, the Gnostics,

Guirdham suggests as much, writing,

Perhaps, too, there is another answer, suggested in his books:

Sources

|