|

by Rodrigo Fernandez, Tobias J. Klinge, Reijer Hendrikse and Ilke

Adriaans

February 05,

2021

from

TribuneMag Website

|

About the Authors

-

Rodrigo Fernandez is a senior researcher at the Centre

for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO).

He

has published on offshore financial centres, shadow

banking, real estate and financialisation.

- Tobias J. Klinge is a PhD candidate at KU Leuven, the

University of Leuven.

He

works on corporate financialisation processes.

- Reijer Hendrikse is a postdoctoral researcher based at

the Vrije Universiteit Brussel.

- Ilke Adriaans is a researcher and policy advisor at

the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations. |

A handful

of Big Tech corporations

now wield more

power

than most

national governments.

It's time to

subject them to democratic control

before their

power erodes democracy.

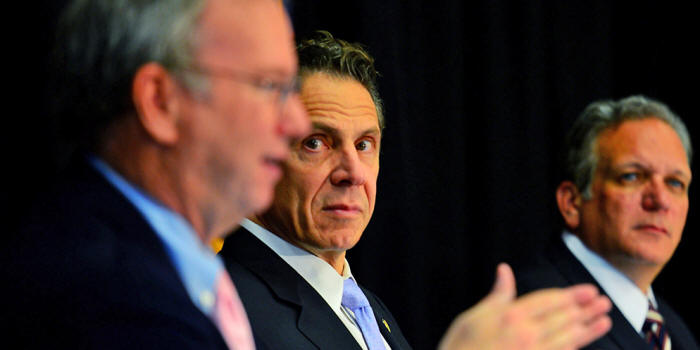

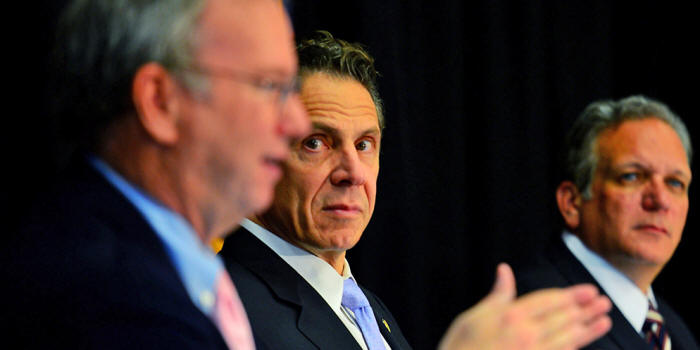

A few months since the pandemic forced societies into digital

interfaces under conditions of lockdown and social distancing,

Naomi Klein noted how a high-tech 'Pandemic

Shock Doctrine' was shaping up. In the US, tech

billionaires like Microsoft founder

Bill Gates and former Google

executive Eric Schmidt were invited by New York governor

Andrew Cuomo to discuss the digitization of state functions and

tackle the Covid crisis.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo

looks on as Google executive chair Eric Schmidt, left,

talks during the Smart Schools Commission report

at Mineola Middle School on Oct. 27, 2014 in Mineola, N.Y.

Photo: Alejandra Villa-Pool/Getty Images

Source

In the UK, Big

Techs were

invited to Downing Street to discuss the tech solutions required

to overcome Covid-19, which saw the surveillance giant Palantir earn

lucrative contracts to streamline data flows across the state.

Ministers from

France and Germany lauded the launch of the new cloud computing

strategy

Gaia-X, designed to enhance 'digital sovereignty' across the

European Union - only to give front-row seats to the usual American

Big Tech suspects.

Today, a handful of

Big Tech monopolies form

the infrastructural core of an ever-expanding tech universe,

operating as obligatory digital interfaces for social exchange -

colonising professional life and private consumption, monopolizing

flows of information and communication.

In the latter case,

the digital platforms that abetted the rise of the far-right joined

forces to banish Donald Trump from the digitized public sphere after

inciting violence in Washington, D.C.

While we might feel

relieved to be rid of Trump's digital tirades, and although there

are legitimate arguments for Big Tech countering imminent political

violence, these developments illustrate the mounting unchecked power

these companies wield over social life.

In

a recent report for the Dutch Centre for Research on Multinational

Corporations, we investigated the financial accounts of the

world's largest digital technology firms in order to come to grips

with the fuzzy notion of 'Big Tech'.

Zooming in on the

apex of capital accumulation unfolding at the frontier of capitalist

development, we analyzed how these companies extract income from

their respective positions in the digital economy, and how these

strategies are augmented by financial techniques and translated into

stellar profits and unmatched resources used to expand their

platformed monopolies in both scale and scope.

Unmatched

Financial Firepower

As

a proxy for Big Tech's infrastructural core, we focused on five

US firms (Alphabet/Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and

Microsoft) and two of their Chinese counterparts (Alibaba and

Tencent).

Compared to S&P 500

corporations, Big Tech firms have considerable more financial assets

at their disposal and follow a business model that relies on what

are known as intangible assets: patents, data, or goodwill.

In the past year,

Big Tech's combined financial assets stood at a staggering $631

billion, on top of a combined total debt of $295 billion.

In October 2020,

-

Apple

-

Microsoft

-

Amazon

-

Alphabet,

...had each crossed the

threshold of a $1 trillion market capitalization.

This shows that

the financial firepower of our Big Tech firms is unrivalled, and

that the chances of newly-minted platforms to mature and remain

independent are increasingly limited, as the incumbents can easily

acquire competitors.

An important marker

of Big Tech's growing monopoly power is the rising value of goodwill

on their balance sheets, which are premiums paid for the acquisition

of another firm.

Goodwill on the

balance sheet of Big Tech (minus Apple) increased by 557 percent

from $23 billion in 2010 to $149 billion in 2019, compared to just

63 percent growth in goodwill for the aggregate S&P 500

corporations.

Furthermore, they

achieve outstanding profits.

Compared to other

S&P 500 corporations, whose net income as share of net sales hovered

around 10 percent in recent years, our seven Big Tech companies

(minus Amazon, for accounting techniques understating the company's

profitability) achieve a level of profitability that is at least

twice as high.

Based

on our financial analysis, we have developed what we call the 'Big

Tech model'.

Although the exact

business models of our seven Big Techs differ, they share common

strategies which revolve around,

While rentiership

and financialization are recurring phenomena in the history of

modern capitalism, platformization is how these features are

presently expressed and augmented under digital capitalism.

As argued by

philosopher

Nick Srnicek, digital platforms are intermediary

infrastructures that thrive on network effects.

Neatly illustrated

by Amazon's 'get big fast' credo, platforms are designed to capture

market share as quickly as possible. The resulting data generated

through scaling up can then be analyzed and turned into marketable

products for commercial and political customers.

In their own ways,

our seven Big Techs have all scaled up into platform monopolies,

allowing for the extraction of significant rents.

Following

geographer

Brett Christophers, rent extraction can be understood as

income derived from owning or controlling scarce assets - such as

data or a loyal customer base - under conditions of little if any

competition.

Platforms typically

extract rents either through selling advertising or levying

commissions on transactions.

How particular

monopoly rents are being turned into money and further refined can

be understood by considering the companies' financialization

dynamics - that is, their operations in financial markets and

through financial instruments.

Our empirical

findings

underscore the notion of a Big Tech model operating as a machine

dedicated towards ever-expanding rent extraction that can be

properly understood in its contemporary context only, as opposed to

an a historical and surprising aberration in the socioeconomic

landscape.

Specifically,

the breadth and depth of rampant digitization invites us to rethink

the logics of capitalism.

'there is

really something qualitatively distinct about the forces of

production that eat brains, that produce and instrumentalize and

control information.'

Shoshana Zuboff goes as far as claiming that the rise of Big

Tech has given rise to 'a new logic of accumulation' known as

surveillance capitalism, geared toward data extraction and

behavioral modification.

Yet critics argue

that despite these novelties, Big Tech firms merely augment

pre-existing capitalist tendencies. These include capitalism's late

nineteenth century embrace of the large corporation, heralding the

ascent of monopoly capitalism and rentierism.

In other words,

what is new is not the tendency towards monopoly, but rather,

the

rampant commercialization of digital footprints...

Given the

self-reinforcing market-conquering logics of the Big Tech model at

work, the seven Big Techs (5 of which are

headquartered in the US, namely Alphabet-Google,

Apple, Amazon,

Facebook and

Microsoft, and 2 in China, namely

Alibaba and Tencent) are likely to dominate the tech universe

for the time being, with thousands of smaller platforms orbiting

around them, and millions of applications built on top of them - all

relying on its core infrastructure, and paying rent for doing so.

With each firm

having cornered its own monopoly, Big Tech as a whole has

effectively come to colonize key forms and means of social exchange,

broadly defined, overlaying the ways in which people used to

interact via digital interfaces for,

-

communication (Facebook, Tencent)

-

information

(Alphabet)

-

work

(Microsoft)

-

consumption

(Alibaba, Amazon)...

In setting the

standards for software toolkits (Google's Android, Apple's iOS) and

programs (Microsoft's Office 365), and spearheading the development

of the hardware to enable exchange (Apple's iPhone), Big Tech has

become the obligatory interface for all types of exchange in the

digital economy.

It is as if a new

screen now overlays economy and society, with Big Tech functioning

as its underlying operating system, increasingly subjecting the rest

of the world to its imposing and intrusive logics.

With

the increasing platformization of capitalism, we anticipate that

scholars will direct their attention to what might eventually be

labeled the 'platform state'.

Besides

accumulating rents, Big Tech companies have also built up

substantial power over economy and society, including

infrastructural power vis-à-vis sovereign states.

Political economist

Benjamin Braun has studied how

Central Banks exert power through

financial markets, creating various interdependencies between public

and private domains and interests.

This

infrastructural core is continuously refined through data extraction

and analysis, accumulating more rent and power in a self-reinforcing

feedback loop which augments the tech dependencies of states:

where the

management of the pandemic has seen governments worldwide

embrace the services of Big Tech, shutting up Trump underscores

the extent to which Big Tech polices our rapidly-digitized

public sphere - but according to standards they invariably set

themselves...

That said, as

Western liberal democracies fall under the infrastructural spell of

American Big Techs, where the deepening of tech-driven governance

requires the increasing rollback of liberal protections by design,

as in the case of

Palantir's

policing services, we need to redirect our gaze

towards Beijing

to fully grasp how Big Tech's infrastructural power becomes inter-digitized

with - and central to - political control...

This brings us to,

the geopolitical angle of Big Tech and the geo-economic, military,

and technological rivalry between the US and China, which promises

to sharpen over the decades to come.

The disruptive

potential of Big Tech is also visible in existing multilateral and

bilateral frameworks for trade and investment.

The way platforms

monetize their operations is not compatible with the principles that

were created to regulate corporate activities in the physical world.

For one, Big Tech is at odds with the existing cross-border

allocation of tax rights, and as a result our Big Techs largely live

tax-free lives in offshore wonderland.

How to tax Big Tech

remains an open question and is subject to fierce diplomatic

contestation.

The speed at which

the sector has developed into a focal point on the stock market, in

political communication, in geopolitics, and in daily life sharply

contrasts with the much slower pace at which civil society and

decision-making bodies have been able to grasp the transformative

nature of these firms.

Big Tech's opacity

has so far provided it with an advantage and left regulators to play

catch-up.

However, on both

sides of the Atlantic, we are now seeing early signs of change.

Lawmakers worldwide,

have to rein in the mounting power of Big Tech, before Big Tech

absorbs the power of democratically-elected governments...

Big Tech companies

have become highly-financialized cash machines for their

shareholders and executives.

These developments are reminiscent of

earlier transformative epochs, not least the second half of the

nineteenth century.

Back then, new

means of transportation and communication came to remodel the

socio-economic order of the day in gales of 'creative destruction',

resulting in excessive wealth and power in the hands of the

so-called Robber Barons...

Then, as now,

existing regulations failed to counteract this new technology-driven

regime centered on monopolies, sparking a popular backlash which,

brought the Gilded Age to an end...

As such, the past

also suggests,

how to approach the Big Tech Barons of today's

New

Gilded Age, which at minimum requires a serious update of the

outdated competition and tax policies presently failing to rein in

Big Tech.

We need to urgently

reflect on the possible ways in which societies can rein in what we

in the report have called the looming 'Big

Technification of

everything', going beyond free market imperatives to break up the

Big Tech monopolies, or simply break open their data treasure

chests.

We need to

contemplate the ways in which consumers or users might reclaim

ownership over data as citizens, ideally short-circuiting the core

operating logics of surveillance capitalism:

-

one way

might be to embrace 'open source' solutions to circumvent

Big Tech enclosure

-

another way

is to take the infrastructural core of Big Tech into public

hands altogether, recognizing them for the crucial public

utilities they are

In any case, we

urgently need to come to terms with the ways which Big Tech has

become the underlying operating system of our age, and consider

rewriting its codes to appropriate its spoils for more meaningful

ends...

|