|

by Fiona Macrae

May 21, 2010

from

DailyMail Website

|

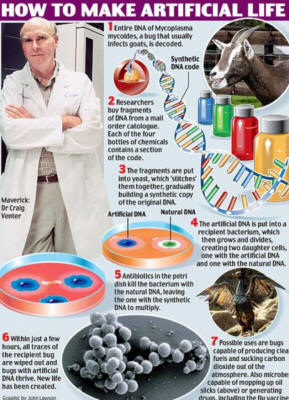

Scientist

accused

of Playing God after creating Artificial Life by making

Designer Microbe

from Scratch.

But

could it wipe

out humanity? |

Scientists today lined up to air their

fears over a genome pioneer's claims that he has created artificial

life in the laboratory.

In a world first, which has alarmed many, maverick biologist and

billionaire entrepreneur

Craig Venter, built a synthetic

cell from scratch.

The creation of the new life form, which has been nicknamed 'Synthia',

paves the way for customized bugs that could revolutionize

healthcare and fuel production, according to its maker.

But there are fears that the research, detailed in the journal

Science, could be abused to create the ultimate biological weapon,

or that one mistake in a lab could lead to millions being wiped out

by a plague, in scenes reminiscent of the Will Smith film I Am

Legend.

While some hailed the research as 'a

defining moment in the history of biology', others attacked it as 'a

shot in the dark', with 'unparalleled risks'. The team involved have

been accused of 'playing God' and tampering 'with the essence of

life'.

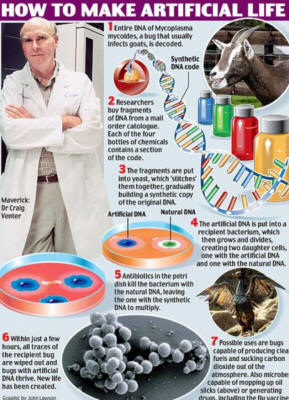

Dr Venter created the lifeform by synthesizing a DNA code and

injecting it into a single bacteria cell. The cell containing the

man-made DNA then grew and divided, creating a hitherto unseen

lifeform.

Kenneth Oye, a social scientist at the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology in the U.S., said:

'Right now, we are shooting in the

dark as to what the long-term benefits and long-term risks will

be.'

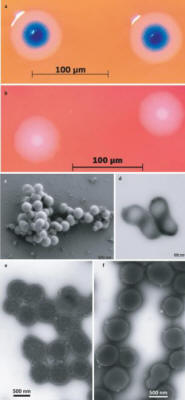

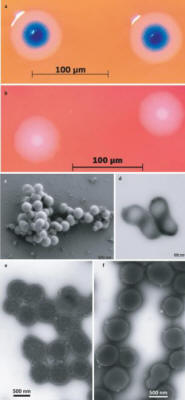

This

picture shows the colonies of

the artificial lifeform nicknamed 'Synthia'

Pat Mooney, of the ETC group, a technology watchdog

with a special interest in synthetic biology, said:

'This is a Pandora's box moment -

like the splitting of the atom or the cloning of Dolly the

sheep, we will all have to deal with the fall-out from this

alarming experiment.'

Dr David King, of the Human

Genetics Alert watchdog, said:

'What is really dangerous is these

scientists' ambitions for total and unrestrained control over

nature, which many people describe as 'playing God'.

'Scientists' understanding of biology falls far short of their

technical capabilities. We have learned to our cost the risks

that gap brings, for the environment, animal welfare and human

health.'

Professor Julian Savulescu, an

Oxford University ethicist, said:

'Venter is creaking open the most

profound door in humanity's history, potentially peeking into

its destiny.

'He is not merely copying life artificially or modifying it by

genetic engineering. He is going towards the role of God:

Creating artificial life that could never have existed.'

He said the creation of the first

designer bug was a step towards

'the creation of living beings with

capacities and a nature that could never have naturally

evolved'. The risks were 'unparalleled',' he added.

And he warned:

'This could be used in the future to

make the most powerful bioweapons imaginable. The challenge is

to eat the fruit without the worm.'

Dr Venter, who was instrumental in

sequencing the

human genome, had previously

succeeded in transplanting one bug's genome - its entire cache of

DNA - into another bacterium, effectively changing its species.

He has taken this one step further, transplanting not a natural

genome but a man-made one. To do this, he read the DNA of

Mycoplasma mycoides, a bug that infects goats, and recreated it

piece by piece.

The fragments were then 'stitched together' and inserted into a

bacterium from a different species. There, it sprang to life,

allowing the bug to grow and multiply, producing generations that

were entirely artificial. The transferred DNA contained around 850

genes - a fraction of the 20,000 or so contained in a human's

genetic blueprint.

In future, bacterial 'factories' could be set up to manufacture

artificial organisms designed for specific tasks such as medicines

or producing clean biofuels.

The technology could also be harnessed to create environmentally

friendly bugs capable of mopping up carbon dioxide or toxic waste.

Dr Venter, a 63-year-old Vietnam War veteran known for his showman

tendencies, said last night:

'We are entering a new era where

we're limited mostly by our imaginations.'

But the breakthrough, which took 15

years and £27.7million to achieve, opens an ethical Pandora's box.

Ethicists said he is 'creaking open the most profound door in

humanity's history' - with unparalleled risks.

Dr Venter, whose team of 20 scientists includes a Nobel laureate,

likens the process to booting-up a computer.

Like a program without a hard drive,

the DNA doesn't do anything by itself. But, when the software is

loaded into the computer - in this case the second bacterium -

amazing things are possible, he said.

|

'WATERMARKING' DNA

This dramatic development naturally raises fears of the

dangers these organisms pose. So one idea, which has

been followed through by Venter and his team, is to

'watermark' them.

By weaving these hidden codes in it enables scientists

to trace the organisms to their laboratories and prove

the recipient bacteria contained the synthetic genome.

Researchers used the 'alphabet' of genes and proteins to

spell out messages.

The team created a code that spells out the 26 letters

of the alphabet, the numbers 0 to 9 and several

punctuation marks. They then wrote a message which

reveals the code. A second missive was a string of

'letters' corresponding to the names of 46 people

involved in the project. A third gave an e-mail address

where people can write once they crack the code and the

fourth listed three philosophical quotes. |

Now that the scientist, whose J Craig Venter Institute has

labs in California and Maryland, has proved the concept, the path is

open for him to alter the 'recipe' to create any sort of organism he

chooses.

At the top of his wish-list are bugs capable of producing clean

biofuels and of sucking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. Other

possibilities include designer microbes that can mop up oil slicks

or generate huge quantities of drugs, including the flu vaccine.

Any such organisms would be deliberately 'crippled' so that they

cannot survive outside the lab, he claimed.

Brushing aside the ethical concerns of his work, Dr Venter wrote in

his autobiography that it would allow,

'a new creature to enter the world'.

'We have often been asked if this

will be a step too far,' he said. 'I always reply that - so far

at least - we are only reconstructing a diminished version of

what is out there in nature.'

Last night, he claimed the breakthrough

had changed his views on the definition of life.

'We have ended up with the first

synthetic cell powered and controlled by a synthetic chromosome

and made from four bottles of chemicals,' he said.

'It is pretty stunning when you just replace the DNA software in

a cell and the cell instantly starts reading that new software

and starts making a whole new set of proteins, and within a

short while all the characteristics of the first species

disappear and a new species emerges.

'That's a pretty important change in how we approach and think

about life.'

The process was carried out on one of

the simplest types of bacteria, under strict ethical guidelines.

The research team insist that they

cannot think of a day when the technology could be used to create

animals or people from scratch.

Has he created

a monster?

by Michael Hanlon

Science Editor

The creation of a living being in a laboratory is one of the

staples of science fiction. Now it is a scientific fact.

Yesterday's announcement of the birth of

a 'synthetic cell' - made by injecting a bacterium shell with

genetic material created from scratch by scientists - raises many

questions.

There are fears the

research could be abused and lead to millions being

wiped out by a plague

like in the Will Smith film I Am Legend

These range from the mundanely practical - how will this be useful?

- to the profoundly philosophical - will we have to redefine what

life is?

Depending on your viewpoint, it is either a powerful testament to

human ingenuity or a terrible example of hubris - and the first step

on a very dangerous road. To understand what this development means,

we need to discover who the team behind this innovation is.

It is led by Craig Venter, the world's greatest scientific

provocateur, a 63-year-old Utah-born genius, a Vietnam veteran,

billionaire, yachtsman, and an explorer. Above all he is a showman.

A master of self-publicity, he does not do things by halves; he led

the private team which competed with scores of publicly funded

scientists in the U.S. and UK to 'crack' the human genome by

sequencing our DNA.

His rapid, innovative approach led to the possibility he would beat

the scientific establishment.

So, to save face all round, the human genome was presented as a

joint achievement. At around the same time, he began talking

about making an artificial lifeform in the lab.

Not a Frankenstein's monster, or even a mouse, but a bacterium, one

of the simplest living organisms. His blueprint was to be an

unassuming and harmless little germ with only 485 genes (humans have

around 25,000).

Venter talks grandly of a supercharged biotech revolution, with

synthetic bacteria designed to produce biofuels, to mine precious

metals from rocks and industrial waste, to digest oil slicks and

render toxic spills harmless.

|

WHO IS CRAIG VENTER?

Craig Venter is a controversial biologist and

entrepreneur who led the effort by the private sector to

sequence the human genome.

He was vilified by the scientific community for turning

the project into a competitive race but his efforts did

mean that the human genome was mapped three years

earlier than expected.

Born in 1946, Dr Venter was an average scholar with

a keen interest in surfing.

It was while serving in Vietnam and tending to wounded

comrades that he was inspired to become a doctor.

During his medical training he excelled in research and

was quick to realize the importance of decoding genes.

In 1992 he set up

the private

Institute for Genomic Research.

Then a mere three

years later he stunned the scientific establishment by

revealing the first complete genome of a free-living

organism that causes childhood ear infections and

meningitis.

In 2005 he founded the private company

Synthetic Genomics,

with the aim of engineering new life forms the would

produce alternative fuels.

He was listed on Time Magazine's 100 list of the most

influential people

in both 2007 and 2008. |

Scientists could even create bacteria which can produce novel drugs

and vaccines, or organisms engineered to live on Mars and other

planets.

The potential is huge - but so are the dangers.

An artificial species, created in the

lab, might not 'obey the rules' of the natural world - after all,

every living being on Earth has evolved over three billion years,

when a myriad of competing species have had to share the same

increasingly crowded environment.

It is possible to imagine a synthetic microbe going on the rampage,

perhaps wiping out all the world's crop plants or even humanity

itself.

Synthetic biology also challenges our most cherished notions

of what life itself actually is. Non-scientists might not realize

that we have, as yet, no proper definition of life.

A diamond is not alive; a baboon clearly is. But what about a virus?

Viruses, which are even simpler than bacteria, have a

genetic code written in DNA (or its cousin RNA).

The stuff viruses are made from is the stuff of life - protein coats

and so on - yet they cannot reproduce independently.

Like diamonds, they can be grown into crystals - and you certainly

cannot crystallize baboons. Most biologists say viruses are not

alive, and that true biology begins with bacteria.

So is Synthia, Venter's tentative name for his new critter, alive?

It is certainly not the result of

Darwinian evolution, one of the

(many) definitions of life. It is more 'alive' than any virus but it

is the product of Man, not of evolution. Its genetic code is simple

enough to be stored on a computer (but then again, so is ours).

Whatever the answer to this fundamental question, Venter's

breakthrough is certainly the final rebuttal to the old notion of a

vital spark - a mysterious essence that divides the quick

from the dead. If you can carry around a genome on a computer memory

stick and make a cell using a few simple chemicals, then the old

idea of 'vitalism' is truly dead.

Of course, this is early days. It is not yet clear if Venter can

negotiate the final step - creating a whole cell from scratch, using

no bits of existing living organisms at all.

His bacterium is likely to be weak and feeble; we are a long way

from synthetic super-plagues, and even further from an artificial

animal or plant. But it is hard to escape the feeling that a

boundary has been crossed.

The problem is, it is far from clear

where we go from here.

Video

|