|

by Caroline Haskins

Article also HERE

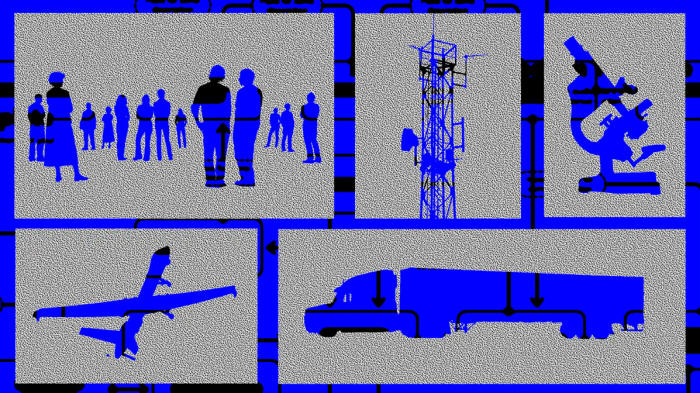

Getty Images a data broker, a data miner, or a giant database of personal information.

In reality, it's none of these - but even former employees struggle to explain it...

Palantir is arguably one of the most notorious corporations in contemporary America.

Cofounded by libertarian tech billionaire Peter Thiel, the software firm's work with Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the US Department of Defense, and the Israeli military has sparked numerous protests in multiple countries.

Palantir has been so infamous for so long that, for some people, its name has become a cultural shorthand for dystopian surveillance.

But a number of former Palantir employees tell WIRED they believe the public still largely misunderstands what the company actually does and how its software works.

Some people think it's a data broker that buys information from private companies and resells it to the government.

Palantir has tried to correct the record itself in a series of blog posts with titles like,

In the latter, Palantir explains that,

The problem, however, is that even ex-employees struggle to provide a clear description of the company.

Xia was one of 13 former Palantir staffers who signed an open letter published in May arguing that the company risks being complicit in authoritarianism by continuing to cooperate with the Trump administration.

She and other former Palantir staffers who spoke to WIRED for this story argue that, in order to grapple with Palantir and its role in the world, let alone hold the company accountable, you need to first understand what it really is.

It's not that former employees literally don't know what Palantir is selling.

In interviews with WIRED, they spoke fluidly about how its software can connect and transform different kinds of data collected by government agencies and corporations.

But when asked to, say, name its direct business competitors, two former Palantir employees who requested anonymity to speak freely about their experiences, struggled to come up with anything.

Juan Sebastián Pinto, who worked as a content strategist at Palantir and also signed the open letter, says it sells software to other businesses, a category commonly referred to in Silicon Valley as B2B SaaS.

Another former staffer says Palantir provides,

So what sets Palantir apart?

Part of the answer may lie in Palantir's marketing strategy. Pinto says he believes that the company, which recently began using the tagline "software that dominates," has cultivated its mysterious public image on purpose.

Unlike consumer-facing startups that need to clearly explain their products to everyday users, Palantir's main audience is sprawling government agencies and Fortune 500 companies.

What it's ultimately selling them is not just software, but the idea of a seamless, almost magical solution to complex problems.

To do that, Palantir often uses the language and aesthetics of warfare, painting itself as a powerful, quasi-military intelligence partner.

Palantir sends its employees to work inside client organizations essentially as consultants, helping to customize their data pipelines, troubleshoot problems, and fix bugs.

It calls these workers "forward deployed software engineers," a term that appears to be inspired by the concept of forward-deployed troops, who are stationed in adversarial regions to deter nearby enemies from attacking.

A former Palantir employee tells WIRED that the company also has code words for certain job titles like,

...which they say are sourced from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization's (NATO) phonetic alphabet of code words meant for use over military radio.

A different former employee tells WIRED that Palantir staffers will often use the military term "FYSA," or "for your situational awareness," instead of "FYI."

Many Palantir emails, they say, also begin with "BLUF:" or "bottom line up front," followed by a short summary of key details or events. (It's essentially the military equivalent of "TLDR," or "too long didn't read.")

The ex-staffer says this jargon can be traced back to Palantir's first clients, which included US intelligence and military agencies.

But arguably Palantir's most recognizable jargon is borrowed from the Lord of the Rings universe.

In response to a detailed request for comment from WIRED, Palantir spokesperson Lisa Gordon said in a statement that the company is,

Gordon added that the open letter criticizing Palantir was only signed by a small portion of the company's approximately 8,000 employees and alumni.

Dawn of Big Data

Its pitch to potential customers is

that they can buy one system and use it to

replace perhaps a dozen other dashboards and

programs, according to a 2022

analysis of Palantir's offerings published

by blogger and data engineer Ben Rogojan.

Crucially, Palantir doesn't reorganize a

company's bins and pipes, so to speak, meaning

it doesn't change how data is collected or how

it moves through the guts of an organization.

Instead, its software sits on top of a

customer's messy systems and allows them to

integrate and analyze data without needing to

fix the underlying architecture.

In some ways,

it's a technical band-aid.

In theory, this makes Palantir particularly well suited for government

agencies that may use state-of-the-art software

cobbled together with programming languages

dating back to the 1960s.

Palantir began

gaining steam in the 2010s, a decade when

corporate business discourse was dominated by

the rise of "Big

Data."

Hundreds of tech startups popped up

promising to disrupt the market by leveraging

information that was now readily available

thanks to smartphones and internet-connected

sensors, including everything from global

shipping patterns to the social media habits of

college students.

The hype around Big Data

put

pressure on companies, especially legacy

brands without sophisticated technical know-how,

to upgrade their software, or else risk looking

like dinosaurs to their customers and investors.

But it's not exactly easy or cheap to upgrade

computer systems that may date back years, or

even decades.

Rather than tearing everything

down and building anew,

companies may want a solution designed to be

slapped on top of what they already have.

That's

where Palantir comes in...

Palantir's software is designed with

nontechnical users in mind. Rather than relying

on specialized technical teams to parse and

analyze data, Palantir allows people across an

organization to get insights, sometimes without

writing a single line of code.

All they need to

do is log into one of Palantir's two primary

platforms:

Foundry focuses on

helping businesses use data to do things like

manage inventory, monitor factory lines, and

track orders.

Gotham, meanwhile, is an

investigative tool specifically for police and

government clients, designed to connect people,

places, and events of interest to law

enforcement.

There's also

Apollo, which is like

a control panel for shipping automatic software

updates to Foundry or Gotham, and the Artificial

Intelligence Platform, a suite of AI-powered

tools that can be integrated into Gotham or

Foundry.

Foundry and Gotham are similar:

Both ingest data

and give people a neat platform to work with it.

The main difference between them is what data

they're ingesting.

Gotham takes any data that

government or law enforcement customers may

have,

including things like crime reports, booking

logs, or information they collected by

subpoenaing a social media company.

Gotham then extracts every

person, place, and detail that might be

relevant.

Customers need to already have the

data they want to work with - Palantir

itself does not provide any.

A former Palantir

staffer who has used Gotham says that, in just

minutes, a law enforcement official or

government analyst can map out who may be in a

person's network and see documents that link

them together.

They can also centralize

everything an agency knows about a person in one

place, including their eye color from their

driver's license, or their license plate from a

traffic ticket - making it easy to build a

detailed intelligence report.

They can also use

Gotham to search for a person

based on a characteristic, like their

immigration status, what state they live in, or

whether they have tattoos.

The sales pitch for tools like

Foundry and

Gotham is that they can transcend all of the

challenges associated with storing and

structuring data, and naturally bring

investigations and business decision-makers to

the correct solution.

With an objectively

superior technology, the thinking goes, the best

possible outcomes will follow.

A version of this logic pervades the internal

culture at Palantir.

When asked what

distinguishes it from other tech companies,

former employees consistently mentioned its

"flat" staffing structure. Engineers can

laterally move to more prestigious or

challenging projects if they prove worthy based

on their skills and connections.

One former

staffer tells WIRED that this made the company

feel like a meritocracy where the best people,

and the best ideas, naturally rise to the top.

Some former employees say that Palantir's

meritocratic culture helped cultivate a sense of

loyalty among staff. But they also believe that

this can make it difficult to speak out against

the company or its business decisions.

(Gordon

said that Palantir "prides itself on a culture

of fierce internal dialog and disagreement on

difficult issues related to our work.")

During her time at Palantir,

Xia says she worked

exclusively with private businesses using

Foundry.

However, she felt a nagging discomfort

about the military work happening in other parts

of the organization.

"I did the thing that I

think a lot of people do," Xia says, "which is,

I just didn't engage with it."

Since leaving Palantir, Pinto says he's spent a

lot of time reflecting on the company's ability

to parse and connect vast amounts of data.

He's

now deeply worried that an authoritarian state

could use this power to "tell any narrative they

want" about, say, immigrants or dissidents it

may be seeking to arrest or deport.

He says that

software like Palantir's doesn't eliminate human

bias.

People are the ones that choose how to work with

data, what questions to ask about it, and what

conclusions to draw.

Their choices could have

"positive outcomes", like ensuring enough

Covid-19 'vaccines' are delivered to

vulnerable areas.

They could also have

devastating ones,

like launching a

deadly airstrike, or

deporting someone.

In some ways, Palantir can be seen as an

amplifier of people's intentions and biases.

It

helps them make evermore precise and intentional

decisions, for better or for

worse...

But this may

not always be obvious to Palantir's users.

They

may only experience a sophisticated platform,

sold to them using the vocabulary of warfare and

hegemony. It may feel as if objective

conclusions are flowing naturally from the data.

When Gotham users connect disparate pieces of

information about a person, it could seem like

they are reading their whole life story, rather

than just a slice of it.

"It's a really powerful tool," says one former Palantir employee.

"And when it's in the wrong hands, it can be

really dangerous. And I think people should be really scared

about it."

|