|

at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2 December 2023.

Photo by Amr

Alfiky/Reuters of global diplomacy to transcend the current pathetic bargaining of national and commercial interests...

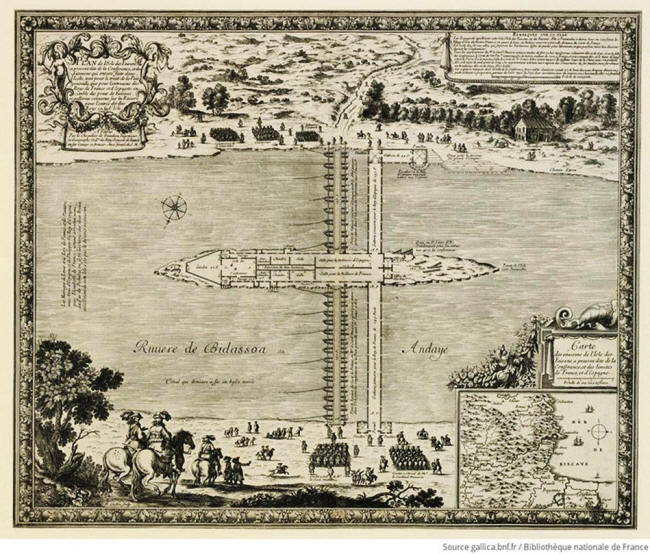

On 31 July 2024, an intriguing ceremony took place on Pheasant Island, a tiny sliver of land in the river Bidasoa, marking the border between France and Spain in the Basque Pyrenees.

Under a lush canopy of trees, a handful of people disembarked from rubber dinghies and walked towards a monument, the only man-made structure on the island. Most of them were wearing the pristine white uniforms of the French and Spanish navies.

The walk was a short one, as the island is only 200 meters long and 40 meters wide.

On the flagpole, the Spanish bandera was lowered and the French tricolore hoisted.

The island's anthem - yes, it has one, despite being uninhabited - was played. The atmosphere was a unique blend of solemn military protocol and gleeful exuberance, just like it was the previous year and the years before.

Every year on 31 July, France reassumes sovereignty over Pheasant Island, six months after it has been transferred to Spain.

Courtesy hendaye.fr

The island, with an area smaller than a soccer field, changes nationality twice a year.

Pheasant Island is the only example in the world of a temporal condominium, a political territory shared by multiple powers with alternating sovereignty

Governance is, in turns, entrusted to the French and the Spanish naval commanders stationed at Bayonne and San Sebastián, who carry the honorific title of 'viceroy' - a curious title, especially in France, where royalty has ended in exile or decapitation.

In 2022, for the first time, a vicereine was appointed, Pauline Potier, a naval commander and deputy director in the French civil administration.

Upon assuming her functions, she said that the strange fate of the island was more than just amusing folklore:

Plan of Pheasant Island (Île des Faisans) c1660, at the time of the Treaty of the Pyrenees between France and Spain. Courtesy Gallica/Bnf

Pheasant Island (Île des Faisans in French, Isla de los Faisanes in Spanish, Konpantzia in Basque) has been undivided since November 1659.

It was here that the Treaty of the Pyrenees was negotiated and signed, bringing an end to decades of war between France and Spain.

Top diplomats like Cardinal Mazarin and Don Luis Méndez de Haro sat together for months in a temporary building to discuss the terms of peace, including a new border between the two kingdoms, the one that still runs through the Pyrenees today.

Portrait of Jules Mazarin (1658) by Pierre Mignard

The successful peace talks were sealed by a royal marriage six months later when 21-year-old Louis XIV of France, the future Sun King, set foot on the tiny island to receive the Infanta Maria Theresa, daughter of the Habsburg king Philip IV of Spain, as his bride.

She came walking through the Spanish side of the sumptuous pavilion that was decorated by none other than Diego Velázquez, the most brilliant painter of his time.

It served as the capstone to the Peace of Westphalia, the continent-wide settlement that put an end to a century of devastating wars in Europe.

The preceding Thirty Years' War (1618-48) had been the most brutal phase, killing approximately 8 million people.

But diplomacy had brought it to a close and the deal on Pheasant Island completed it.

What happened in Westphalia still shapes the way we conduct international relations today, now on a global scale.

Planetary politics is still very much in its infancy, but the format it takes is invariably diplomatic: the 2015 Paris Agreement, for instance, was negotiated by national diplomatic delegations.

And if the history of diplomacy teaches us one thing, it is that,

By looking back, we may not only find a few insights but also some hope.

Modern diplomacy goes back to early 17th-century Europe from where it spread across the globe. Of course, there is nothing intrinsically 'Western' or 'European' about diplomacy.

For millennia, countries and civilizations have been engaged in formal talks with other countries and civilizations.

Yet something peculiar happened in early 17th-century Europe.

And it was this vision of diplomacy that would become dominant in modern times.

Diplomacy was Distrust clad in Good Manners

When Geoffrey Chaucer was sent as an emissary to Italy between 1372 and 1378, he was basically on personal business trips for Edward III.

The king sought to get a loan from the Florentines, a harbor from the Genoese, and a daughter-in-law from the Milanese.

However, when in the 1620s Cardinal Richelieu, France's principal minister under Louis XIII, established the first modern foreign ministry, its foundational principle was not royal benefit, but raison d'état, the national interest.

The concept had been championed by Niccolò Machiavelli a few decades earlier in Florence, and Richelieu applied it to the Thirty Years' War.

For Richelieu, the modern state was a political organization with a strong centralized power holding exclusive sovereignty over a clearly defined territory.

In order to scrupulously observe the balance of power with other states, highly skilled diplomats had to be organized in a permanent professional corps, with ambassadors settling abroad for years, not months.

Only in this way could they gather all relevant intelligence, report back to the homeland, and engage in what Richelieu called la négociation continuelle...

His vision laid the foundation for the system of sovereign states that was formalized in 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia.

During this first act of diplomatic history (1600-1800), negotiations took place mainly on a bilateral basis:

Diplomacy was about,

It was distrust clad in good manners.

The Ratification of the Treaty of Münster (1648) by Gerard ter Borch II. The treaty was part of the Peace of Westphalia. Courtesy Rijksmusuem

Of course, this new type of diplomacy would not stop all wars, but it became increasingly favored as an alternative to armed conflict.

A good ruler, wrote the influential French diplomat François de Callières in 1716, must not,

Like many others in the Enlightenment, he hoped for a world order built on reason and dialogue rather than religion and war.

When France emerged as the dominant political power on the continent, Richelieu-style diplomacy spread across Europe, and French became the primary language of international affairs, giving us terms like,

As a side-effect, French etiquette and gastronomy gained worldwide prominence.

Whether Richelieu can be fully credited for having introduced the blunt table knife at formal dinners remains uncertain (he is reputed to have abhorred the custom of using knives for picking teeth - or fights), but la nouvelle cuisine française of the 18th century did put entirely new food items like oysters, lobsters, truffles, foie gras and champagne on the menu of the aristocracy from Russia to America.

Life seemed good under the ancient régime, and nothing appeared poised to change it.

A new chapter started with a bang. In 1814, the Austrian foreign minister Prince Klemens von Metternich was convinced that diplomacy had to make a fresh start.

Leisurely bilateral chats by wig-wearing, white-powdered aristocrats sipping coffee or tea in rococo salons while gently discussing some border issue would no longer do.

Napoleon's conquest of continental Europe had shattered the old balance of power, and a radically new brand of diplomacy was needed, one that was built on the consensus of the European governments.

Metternich became to diplomacy's second act what Richelieu had been to the first: its main architect. As a political conservative deeply preoccupied by stability, he favored monarchism over all sorts of revolutionary adventures.

He certainly did not go as far as Immanuel Kant who had suggested that long-lasting peace could be realized by bringing different countries together in a federation of free states, but he did side with,

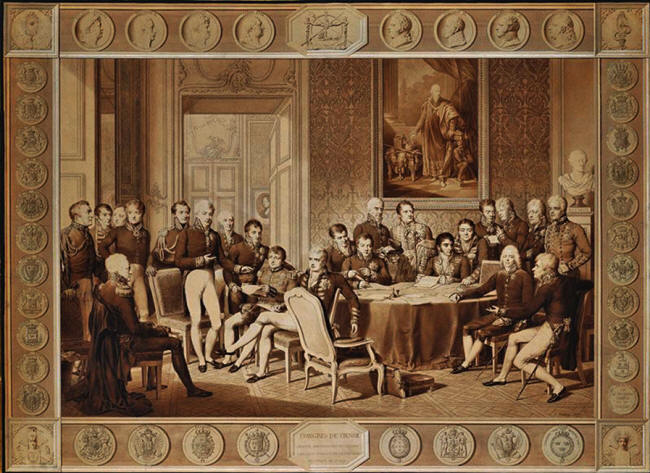

The Congress of Vienna (1815) by Jean-Baptiste Isabey. Courtesy the Royal Collection

Act II of Diplomacy saw the emergence of multilateralism as a foundation of modern diplomacy, and would remain dominant for the next two centuries.

In 1814 and 1815, the Congress of Vienna brought together delegates from five major powers and 12 other nations to deal with the aftermath of Napoleon.

Together, they drew a new map of Europe and crafted a delicate balance of power that was to be overseen by the so-called 'Concert of Europe', a general agreement on multilateral consultation that had never existed before and lasted until the outbreak of the First World War.

If the world changed, diplomacy had to change too...!

La balance politique (1815), formerly attributed to Eugène Delacroix. Courtesy BnF, Paris

The model set up by Metternich in Vienna was soon repeated elsewhere for more topical discussions.

The Berlin Conference of 1884-85 brought together 14 European nations with imperial ambitions to discuss the rules for colonizing Africa.

The Hague conventions of 1899 and 1907 had dozens of countries negotiating the rules of warfare.

The concept of raison d'état remained paramount, but if that ideal could be achieved by multilateral dialogue, all the better.

The rise of Multilateralism did not spell the End of Bilateral Diplomacy

This period of increased international exchange also gave rise to the World's Fairs (first in London, 1851) and the modern Olympic Games (Athens, 1896).

It was multilateralism for the millions:

The First World War ended the Concert of Europe, but not multilateral diplomacy.

After the Second World War, multilateralism was approached even more thoroughly, with the United Nations as its most important outcome.

The UN was meant to succeed where the League of Nations had failed: maintaining world peace.

In the 1950s, just after completing his PhD, Henry Kissinger, wrote that in an age of nuclear threat,

After the end of the Second World War, multilateral institutions flourished: On a regional level, the European Union came about, as did,

...and many others.

The rise of multilateralism did not spell the end of bilateral diplomacy, as countries continued to engage in mutual negotiations. In practice, there was considerable overlap between the two approaches.

Major international conferences would focus on multilateral discussions during plenary sessions while leaving room for bilateral talks during coffee breaks, breakfast meetings and dinner parties.

Classical bilateral diplomacy also spread globally, as countries decolonized and the Cold War ended. What had been a Western style of diplomacy served as a template for many new African, Asian and east European regimes.

The UN membership expanded from 51 members in 1945 to 193 in 2024, adding a new layer of diplomatic dialogue.

Somehow it worked...

For all its shortcomings - multilateral organizations are notoriously unwieldy and bureaucratic - Act II diplomacy has contributed to a safer world.

There has been less warfare between countries in recent decades, and fewer people have died annually from armed conflict in the past 30 years than in the previous century, despite the recent wars in Ukraine, Ethiopia, South Sudan and the Near East.

The result is far from being perfect but, as the former UN secretary-general Dag Hammarskjöld once said,

That minimal program has been achieved, somehow.

That the postwar world has remained free from nuclear warfare is a success story for which multilateral diplomacy deserves more credit than it usually gets.

It was no coincidence that the classic model of multilateral negotiation was chosen when, starting in the 1970s and '80s, an entirely new threat to world peace emerged: global warming.

How was this hell to be averted?

In 1988, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was established - the UN climate panel - followed by the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992, which was signed by 166 countries and now counts 198 parties.

Its highest decision-making body is the annual Conference of the Parties, or COP, which led, among other things, to the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 and the Paris Agreement in 2015.

International climate policy is thus the direct heir to four centuries of diplomatic history.

From the 17th and 18th centuries (the first act), it inherited the notion of sovereign states; from the 19th and 20th centuries (the second act), the willingness to engage in multilateral dialogue.

But raison d'état - the enlightened self-interest of anthropocentric world politics - was thereby anchored at the heart of the fledgling planetary geopolitics.

That could not remain without consequences.

The unexpected climate accord was hailed as,

The main reason for this almost universal praise was a line in the agreement that called on countries to start 'transitioning away from fossil fuels'.

Such explicit language was a first in 28 years of COP.

There was something peculiar about the enthusiasm. Why did it take nearly 30 years - and almost 200 diplomatic delegations - for an annual international climate conference to formally acknowledge what scientists had long shown?

Negotiators had known for decades that climate change is anthropogenic, that fossil fuels cause more than 75 per cent of emissions, and that even modest warming brings serious consequences.

They also knew 2023 was the hottest year on record, at that point. So why did they merely 'call on' countries to 'transition away' from fossil fuels 'by 2050' in an 'orderly' fashion, without binding commitments?

The answer is straightforward: faced with diverging national interests and relentless industrial lobbying, traditional multilateralism has proven tragically inadequate for addressing long-term planetary crises.

Despite the stability and cooperation it once delivered, modern diplomacy is falling short in the face of fundamentally new threats. We have outlived Act II, but not yet entered Act III.

Since the millennium, we've been stuck in an extended intermission, with diplomacy paused while Earth's drama intensifies.

We are Unprepared for the Storms ahead and Unwilling to Redesign the Vessel

And climate change is only one of several critical challenges.

Scientists have identified nine planetary boundaries:

Ocean acidification is now reaching a tipping point.

These threats are "scientifically clear"..., yet none has been met with adequate international action.

In truth, the Earth system is entering uncharted waters, but diplomacy still behaves as if we're in familiar territory. We are unprepared for the storms ahead and unwilling to redesign the vessel.

It is 1814 again - but without Metternich's imagination. Today's diplomats remain bound to institutional tradition, while even the most conservative figures of the past showed greater adaptability.

If an attempt is made to rethink international relations, it usually boils down to another fruitless debate on the much-needed yet never-realized reform of the UN Security Council.

Just as humanity should be uniting to confront its greatest challenge yet - safeguarding the planet's life-support systems - we are more divided and less resourceful than ever.

Regional wars destabilize old power structures, geopolitical shifts create new fault lines, and international agreements unravel.

With each passing year, the UN seems to resemble the world of 1945 more than the world as it might look in 2045 - soon, the organization may follow the same path as the League of Nations.

And each year, COP grows larger, but also more toothless - the power of the fossil fuel lobby is increasing steadily.

At the 2023 climate summit in Dubai, no fewer than 2,456 fossil fuel lobbyists were granted official access passes, four times more than the year before.

Even the presidency was held by one of the fossil sector's top CEOs, the previously mentioned Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber.

He called for reforming these international institutions,

Yet, in the meantime, nothing happens.

While Metternich swiftly reimagined diplomacy after Napoleon, we appear remarkably sluggish in responding to the urgent demands of life on a "burning" planet...

The UN was founded to Manage Conflicts between Countries, not between Humanity and the Planet

The reason why tools from the past won't suffice is that the task involved has become dramatically different.

The planetary polycrisis we are facing is not a regular war, nor even a world war or a global nuclear threat. We are talking about an entirely new form of complexity here, well beyond classical intrahuman conflict.

The polycrisis is anthropogenic in its origin, but it cannot be anthropocentric in its solution.

It has become a physical reality of its own, with its own ever-accelerating dynamics, its own centrifugal forces catapulting the more-than-human consequences away from its human causes.

And here lies the heart of the problem: the Earth system is in deep crisis, but we confront it with the usual solutions of the human world.

No wonder that the existing concepts - national sovereignty, raison d'état, multilateral diplomacy, and so-called stakeholder engagement (a polite term for consultations with lobbyists) - fall so painfully short. The UN was founded to manage conflicts between countries, not to resolve the conflict between humanity and the plane

A flat organization cannot solve a vertical problem.

Where did we go wrong? Somewhere along the road of postwar politics, we have begun to assume that 'international institutions' were synonymous with 'global governance' and that that was enough.

We forgot that the word international meant just that: inter-national, literally between different nations.

That was the logic underlying the conferences in Vienna, Berlin or The Hague. But the planet is more than a sum of countries. Clinging to the multilateral paradigm is like trying to run a country with just a convention of mayors.

No wonder parochial imperatives continue to prevail over planetary needs.

The whole notion of 'foreign policy' feels increasingly meaningless in the age of planetarity.

The clearcut distinction between foreign and domestic affairs comes from a time when the geophysical fiction of borders largely shaped historical societies.

But extreme weather patterns, biosphere integrity, ocean acidification, sea level rise, freshwater change, mass migration, global pandemics and runaway machine intelligence laugh at the political boundaries between nation-states.

This does not mean that we have to do away with borders altogether - they still structure part of our lives - only that we have to start thinking about levels of diplomacy that are not sovereignty-driven.

Beyond the logic of raison d'état, we urgently need to develop the principle of raison de Terre - an encompassing approach that prioritizes the interests of the Earth system above all national considerations.

Pleading for the relativisation of national sovereignty undoubtedly sounds, at first glance, like heresy. It concerns nothing less than the granite foundation of four centuries of modern diplomacy, which still forms the basis of the UN today.

Doesn't the UN Charter itself state that relations between countries must be 'based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all its Members'?

A noble principle, certainly - but the result is that we are no longer capable of viewing the world in any other way than as a colorful puzzle of countries.

This, however, is a very recent reality.

In Children of a Modest Star (2024), the political scientists Jonathan Blake and Nils Gilman argue that, in 1945, half the world's population did not live in a nation-state, but in a mandate territory, colony, protectorate or overseas possession.

Only from around 1965 onwards have nearly all people on Earth lived in modern states.

This, of course, is thanks to the wave of decolonization. Colonies had to become countries, foreign domination had to give way to autonomy, and all these new nations had to be treated as equals.

Wonderful ideals - but they also led to an absolutisation of the principle of sovereignty.

What was in reality a relatively recent and arbitrary development - the world as a jigsaw puzzle of autonomous states - was etched in stone and presented as timeless.

Today, the EU proves that it is possible to add a layer of decision-making that transcends the individual nation-state without denying national dynamics.

The Discrepancy between what People Expect and what Diplomacy Delivers is quite Staggering

Contrary to what social media and political rhetoric often suggest, humanity is much less divided in terms of planetary politics than we tend to think.

A massive poll conducted in 2024 by the UN Development Program and the University of Oxford reveals that 80 per cent of the world's inhabitants want their country to do more about climate change.

With more than 73,000 people surveyed in 77 countries, who together represent 87 per cent of the world's population, it counts as the largest public opinion survey on climate.

The results are eye-opening:

If a very large majority of humanity desires these outcomes, why do a large majority of diplomats fail to enact them?

The discrepancy between what people expect and what diplomacy delivers is quite staggering.

The answer is sobering:

Old-school multilateral diplomacy has hijacked the global conversation on the climate.

Partisan groups with vested interests such as financial and industrial lobbies and major civil society organizations have easier access to the COP negotiators than billions of everyday people whose future it is all about.

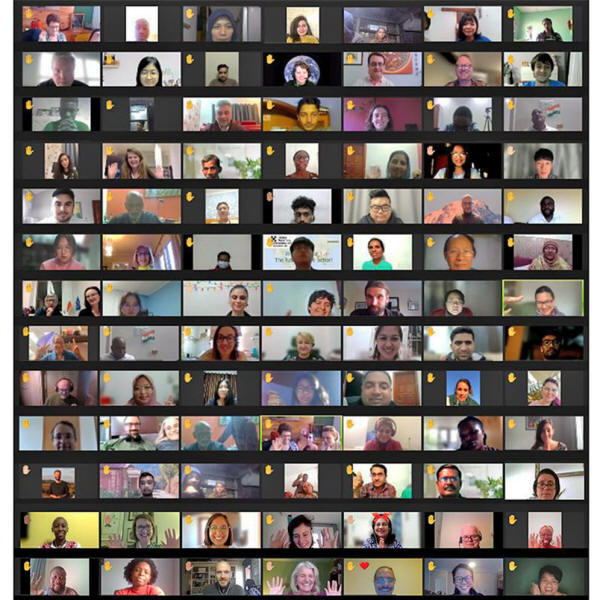

Citizen participants in the 2021 Global Assembly. Courtesy the Global Assembly on the Climate Crisis

It was precisely for this reason that, in October 2021, the very first Global Assembly was held, a bottom-up initiative without formal mandate that drew the attention of the UN secretary-general António Guterres and the COP26 president Alok Sharma.

With the help of a NASA database on human population density, the team behind the project generated a random sample of 100 dots that were plotted on a map of the world.

At each of these dots, they sought a local partner to select four to six everyday citizens through conversations in the street or door-to-door recruitment.

In order to achieve a balance in terms of age, gender, geographical distribution, educational attainment and attitude toward climate change, a final group of 100 participants was drafted by lot from the pool of 675 candidates

The organizers readily acknowledged that the number of participants was too small to be representative of the global population, but this was just a pilot and, with a budget just under $1 million, they did what they could.

The eventual group looked like a pretty good snapshot of the world.

It contained,

During the Assembly, 42 different languages were being used, with English, Chinese and Hindi being the most common.

Participants came from all corners of the world.

In line with global statistics, more than half of them were younger than 35, two-thirds lived on less than $10 a day, more than a third had never used a computer in their life, a third had never attended school, and 10 per cent could neither read nor write.

Sixteen members belonged to an Indigenous community, and six were refugees.

In 12 Weeks, they had Achieved more than COP had in 30 Years

Over a period of 11 weeks, the participants spent 68 hours together online, both in plenary and breakout sessions.

One of the members was Li Shimao, a student from Wuhan, studying international trade; climate change was never a major worry for him.

During the sessions, he met Mohamed Salem, an elderly goat farmer from the Yemenite island of Socotra who had to travel 60 km to get online.

Mohamed told Li and the other assembly members how his goats were suffering from repeated droughts, as the landscape was getting increasingly barren.

There was also Madeleine Kiendrebeogo, a young female domestic worker from Côte d'Ivoire, who exchanged with someone like Chom Chaiyabut, a villager from the forests of southern Thailand.

This random sample of everyday people from the planet had access to information, translation and facilitation in order to articulate and amplify their community voices.

They took their job very seriously and felt incredibly empowered by the process.

Most importantly, together they created the People's Declaration for the Sustainable Future of Planet Earth, a call,

The Declaration advocated for upholding the Paris Climate Agreement - it was therefore not in opposition to classical multilateralism, but built upon it, displaying more ambition and creativity than we usually see at COP conferences.

The Global Assembly, for example, called for a fair distribution of responsibilities based on historical emissions and capacity, inclusive climate action so that,

In 12 weeks, they had achieved more than COP had in 30 years.

At the end, Chom Chaiyabut from Thailand said:

He was not alone in praising what had been achieved.

Even the UN secretary-general Guterres applauded the initiative as,

Suppose such a global citizens' assembly were to become an integral part of the COP meetings.

After a pre-conference online phase, which could involve several million participants, a random sample of 1,000 of them, doing justice to the diversity and demography of the world, would participate.

And suppose they were allowed to deliberate, not just in the Green Zone where visitors and activists stroll, but in the Blue Zone, the heart of the congress, where the official proceedings take place.

And suppose this assembly had access to the best available science on climate change and its causes. They would also hear from national politicians, civil society organizations, private sector actors, religious leaders and Indigenous communities.

At the end, they would deliver their recommendations to the leaders of the world.

Would they need almost 30 years to state the obvious, namely that we have to get out of this fossil nightmare as soon as we can? Most probably not.

They would take planetary custodianship to an entirely different level, well beyond the pathetic bargaining of national and industrial interests at the annual COP conference.

The proposal to include a global citizens' assembly at the heart of international climate diplomacy is less utopian than it might seem at first glance. Ideas in this direction are gaining international traction.

That, at least, was the conclusion I got from the conference in Oxford in July 2024: 'A Permanent Global Citizens' Assembly: Adding Humankind's Voices to World Politics'.

A few months later, an essay by Laurence Tubiana and Ana Toni was published, entitled 'The Case for a Global Climate Assembly'.

The authors were no lightweights:

They, too, recognized that our existing diplomacy was falling short, and suggested involving ordinary people as well.

They pointed to national citizens' assemblies with randomly selected citizens in Ireland and France, and participatory processes in Brazil.

It was shown that randomly selected citizens deliberate more freely and are less hindered by party interests than political elites, resulting in more ambitious and coherent recommendations.

We need Spaces where the World can Speak as the World on the Problems of the World

Tubiana and Toni felt it was high time to bring this approach to the global level, just as Richelieu had brought the raison d'état from the local to the national level:

They wrote that the time is ripe for this.

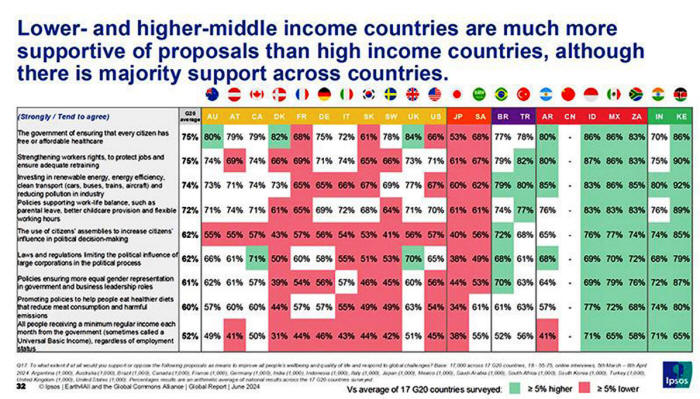

In G20 countries, 62 per cent of citizens support the idea of citizens' assemblies, while in countries such as Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico and South Africa, the figure rises to over 70 per cent, and in Kenya, more than 80 per cent of the population is in favor.

Courtesy Ipsos, Earth4All and the Global Commons Alliance Global Report, June 2024

Their conclusion was as obvious as it was bold:

It is expected that this first attempt to integrate a global citizens' assembly at an international climate summit will face considerable challenges.

While Brazil has a long tradition of participatory processes and social dialogue, it is also an oil-exporting country that in February 2025 joined OPEC+, the forum for oil producers.

This time around, the core assembly will be preceded by a large number of community assemblies worldwide. Organisations from across the globe have been involved in shaping the governance and designing the process.

Particular attention is given to non-Western forms of knowledge.

In diplomacy's third act, we need spaces where the world can speak as the world on the problems of the world. Global climate governance involves deep moral choices about the future of the planet that cannot be left in the hands of national negotiators alone.

For instance,

Even more important will be the debate on geoengineering.

These are such fundamental choices for the world that a large, representative sample of its inhabitants should at least be given the opportunity to weigh in on the appropriateness of such a far-reaching intervention.

There is no shortage of major questions.

Just to name a few:

The question is easy:

We are at a crossroads.

If diplomacy is to have any relevant role in the age of planetarity, it has to update its current multilateral paradigm. Just like the bilateralism of the ancien régime was fundamentally transformed by the cataclysmic events of the Napoleonic era, the multilateral model must be structurally renovated given the catastrophic conditions of our time.

Every 200 years, diplomacy needs an update.

Why wouldn't it be able to renew itself today?

The big question, then, is not whether diplomacy will change, but how. For 400 years, it served the nation-state; in the future, it will have to serve in the name of Earth.

To begin moving in that direction, diplomacy must, as soon as possible, bring the voice of the planet's inhabitants into the heart of its crucial deliberations - not to replace current negotiations, but to complement them, just as Metternich's multilateralism once enriched rather than replaced Richelieu's bilateralism.

At this Juncture, it may be more Instructive to Revisit the Older Traditions of non-Western Diplomacy

At COP or the UN General Assembly, these assemblies may become essential for contemplating the common good and the long term, offering a moral framework for future action.

Ideally, their recommendations would have legal status and become an integral part of the global decision-making process.

To be effective, a follow-up mechanism will need to be integrated. Inspiration can be taken from the first institutionalized citizens' assemblies, like the one in the German-speaking community of Belgium, the first place on Earth where the elected parliament is flanked by a permanent assembly drafted by lot.

Each time everyday citizens make recommendations, elected politicians are obliged to respond.

Whatever its precise form, Act III diplomacy will require a loosening of the raison d'état in favor of the raison de Terre. This may sound as visionary as Kant's 'federation of free states' did in 1795, but two centuries later his idea has materialized, notably in the European Union.

Moreover, the EU exemplifies how the voices of both countries and citizens can be combined in international decision-making, with its delicate balance of power between the national governments and the transnational parliament.

However, diplomacy's third act should not overly fixate on European examples. Sufficient inspiration has been drawn from the West over the past 400 years.

At this juncture, it may be more instructive to revisit the older traditions of non-Western diplomacy, largely overshadowed by the Westphalian system of sovereign states.

Act III diplomacy will, therefore, need the best ideas the world has on offer, in order to succeed.

There is also an obvious need for more demographic justice. China, India and Indonesia are three of the four biggest countries in the world - together, they present more than 38 per cent of the world population. And in 2050, a quarter of the world will be African, as its population will rise to 2.5 billion.

It seems about time that some of their most central philosophical and spiritual ideas help shape global politics of the future.

A number of years ago, I walked the Pyrenean High Route, an 800 km-long trail from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean, following a high course in the mountains that stays as close as possible to the French-Spanish border, the one established so long ago on Pheasant Island.

As I was climbing up and down the granite and limestone border ridge, I found myself cursing more than once at the negotiators of Pheasant Island who had gladly drafted a line on the map without actually getting up there themselves.

But the hike was absolutely magnificent, and gave me ample time to reflect on the beauty and the fragility of the world.

At a given point during my hike, the reality of climate change kicked in with such violence I will never forget. I was camping in front of the brutally beautiful north face of the Vignemale summit, the highest peak on the French side.

At dusk, the silence of the spectacular setting was interrupted when a section of the mountain's easternmost glacier broke loose and came tumbling down its scree slopes in a cloud of dust and stones. The sound - a raw, thunderous roar - was unearthly and deeply unsettling.

That night in my tent, I struggled to find words to write down in my diary.

The following days, I kept on pondering over the event during my climbs. Even if it was too early to find satisfying answers, I began to sense that there was something fundamentally wrong with a system of world politics just based on national sovereignty.

If the broken Vignemale glacier had made one thing clear, it was that private vices did not lead to planetary virtues.

We have already Moved from the Enlightenment to the Age of 'Entanglement'

Later at home, I came to realize that there is a certain Cartesian quality to the Western-style diplomacy that has dominated the world.

Richelieu was reshaping France's foreign policy at the same time that Descartes wrote his Discours de la méthode (published in 1637).

The timing was perhaps not a coincidence.

Just a few years earlier, Galileo Galilei had demonstrated that, not Earth, but the Sun stood in the middle of the planetary dance.

Descartes and Richelieu came up with the metaphysics and politics of self-centeredness, as if something had to be compensated - from geocentric to egocentric, so to speak.

Right after Earth was dethroned from the centre of the solar system, a self-centered perspective became deeply ingrained in the core of Western philosophy and diplomacy, and it has remained there until now.

It continues to shape the way we deal with the planet today, from Pheasant Island to the COPs in Sharm el-Sheikh, Dubai or Baku.

Today, it is time to develop a new geocentric model - not in the astronomical sense, of course, but philosophically: a fundamental awareness that places the Earth system at the centre of our thinking and actions, and that considers the raison de Terre as the keystone of global governance.

Drawing on a wide range of philosophical and spiritual traditions, this geocentric awareness can even look beyond the interests of present generations and strictly human concerns to take into account the distant future and the more-than-human life.

Such a perspective was already pioneered by the Global Assembly when its members unanimously called for,

More than we might realize, we have already moved from the Enlightenment to the age of 'Entanglement'.

|